The following texts constitute a controversy between Paul Vecchiali and Cahiers du cinéma in early 1981. The first is an article by the critic Louis Skorecki in which he expresses his joint disapproval of three contemporary films, two of which are Diagonale productions — C’est la vie !, directed by Vecchiali (rendered in these texts without the ‘official’ exclamation point) and Cauchemar, directed by Noël Simsolo. This is followed by a letter sent by Vecchiali in response and addressed to Cahiers as a whole, which the magazine published in its next issue, along with a response by Skorecki, the third text translated here. According to Vecchiali, as a result either of this polemic or of earlier comments critical of French film journalism (he tells the story differently in different places), Cahiers adopted a uniformly unfavorable editorial line regarding his films, which was only ameliorated several years later when the editorial team learned that Jean-Luc Godard loved Vecchiali’s En haut des marches. Vecchiali reports that, on hearing of this, he said to Cahiers editor Serge Toubiana: ‘The master has spoken, if I understand correctly.’ [1]

Louis Skorecki

Hearing on the radio, in an extremely gripping, dramatized arrangement by Gabriel Yared (cf. the synthesizers in Sauve qui peut (la vie), which make you raise your head), an already old song by Michel Jonasz (‘Guigui’, a heavily melodramatic and crazy story, full of gypsy violins, of amnesia concerning a woman: a colorful portrait of decline, madness and some recollections making their way into memory, the partial recollections of a man whose reason is crumbling — in short, a story not very different from that of Cauchemar by Noël Simsolo), listening to these words once again, I had the very strong impression that French filmmakers, almost all of them, would be better off composing songs. Songs would be more deeply attuned to their ambitions — at least to what emerges from seeing their films.

Not so long ago — it probably began with the songs of Nougaro, ‘La petite fille, Place de la Concorde’, [2] and more recently those of Yves Simon, ‘Au pays de merveilles de Juliette’, his encounters with Ferdinand Godard, [3] etc. — songwriters liked to declare, invoking their mad love for cinema, that a song was a small script that had to be three minutes long, concise, precise, in which everything had to be perfectly arranged and fitted together. Apart from those — Reggiani, for example — who insist on performing their text as an actor would rather than playing the game of the musical miniature, a genre in itself, with its rules of stylization, its obligations towards ruptures, ‘breaks’, montages — apart from these exceptions that are old-fashioned and ‘left bank’, song has benefited from these sung, collected, dramatized short fictions. But cinema? You get the impression that it’s evolved in the opposite direction: as song becomes fictionalized and is definitely seeking new scripts, cinema, for its part, becomes impoverished and loses its romanesque fabric, its consistency. Worse: it often drags stories with only three minutes’ worth of material into an hour and a half. Three French films have come out recently which, despite what makes them different, bear witness to this disease spreading through French cinema — and which we could call ‘how-to-make-it-last?’

Coincidences and symptoms.

As a quick caricature, you could say: it’s not a crisis of subject matter, it’s a crisis of the subjects themselves — it’s not a shortage of profound, sincere stories that is the issue, but the relationship that those who tell these stories have with them, a relationship that is neither profound nor sincere, a relationship of circumstances. Are these filmmakers aware of the absence they instill and drag out in their films — this manner of withdrawing from their own scripts, of letting the phone ring, [4] of not being there for anyone? I’m not so sure they are. The atmosphere in French cinema is not one of detachment or of self-critique. It’s rather one of complacency, of narcissism, of small-mindedness in point of view: narrow creations in confined milieus where they flourish crookedly, badly encouraged by incestuous rumors; you never leave your family, however independent you believe yourself to be — a decidedly stifling, extremely French, self-satisfied family. This is why the choice to single out these three films — linked by current affairs, a series of coincidences — has something necessarily unfair about it, and should not serve in any way to ‘whitewash’ a French cinematic production that has, on average, the same — if not worse — type of flaws.

Claude Berri and Paul Vecchiali both produce their own films and those of other filmmakers — including precisely, in Vecchiali’s case, Cauchemar, Simsolo’s first feature-length film. Despite huge differences that characterize the two types of productions, mainly due to a radical difference in means — Berri can produce Tess, while Vecchiali can only afford Simone Barbès, with all the Virtue and Courage imaginable — huge coincidences abound: a family business in both cases, with Vecchiali casting his sister Sonia Saviange and Berri hiring his own, Arlette Langmann, as his editor; all the characteristics of work in the family and its qualities — the humanity of relationships and atmospheres, specific descriptions, realisms — as well as its flaws — you go around in circles, you bite your own tail. And also: the determination and tenacity to produce, for years, each in his own realm, works of quality — original, intelligently French: a style is established, you find the faces of regular actors, a competitive spirit takes hold — learning on the fly about cinema, the commotion, the emergence of talented technicians. Two filmmaker–producers who form a school, a family, a clan. Who also broaden, little by little, their universe and preoccupations: imperceptibly, you go from very autobiographical obsessions to more external subjects. External to the point of becoming exercises in style.

Songs, songs.

You can say I Love You, That’s the Enchanted Life; or: That’s Life, I Love You in Songs. [5] Je vous aime: a woman loves and leaves men, out of love it seems; we never go deep enough into things to be sure; one thing follows another, each with its own number, in a scattered order, as the filmmakers imagine how memory works; classical, frontal, professional filming; discretion and good taste, humor, light detachment; it’s well-done, pleasant, hollow. Insistently hollow: every time a shadow of profound emotion threatens to appear, lived or analyzed, we move on to something else, to the next number. Next! All in songs: Depardieu sings rock (poorly: he should shed his animal skin, his character of a sensual Michel Simon from the eighties: so many caricatural, exaggerated limitations in his craft as an actor); Gainsbourg does refined post-reggae, poorly synchronized like on TV, efficient; Souchon doesn’t sing, he simply gives his character of a disillusioned bookseller a bit of the old wrinkled child and dreamer side that he puts into his songs, which amounts to the same thing: you leave the music aside, you adapt the lyrics to the character — there’s nothing left to do but act instead of singing, it’s tailor-made and hand-sewn. Beautiful, melodious work. And Deneuve in her all-welcoming blondness, with just the right amount of coldness to be a star, a muse. All in songs, we slide toward the gentle, the inconclusive: every time the verse returns, a moment that repeats itself, the same notes that linger. A film that you hum along to and forget, alternately. Like C’est la vie: a contemporary operetta about a woman who has style and manners; a proper, stylized film, composed entirely of sequence shots and songs. The essential difference between Vecchiali and Berri is that the latter privileges the moment of two people together, the feeling of sophisticated, cushioned, warm solitude, whereas the former prefers a multitude of characters, larger settings, the feeling of a ballet in a hollow setting. But in both: effects of rupture, of the shattering of the dream: in Vecchiali, through the irruption of other characters into the frame — montage within the sequence shot, the heterogeneity of appearances; in Berri, through clean cuts, as if with a knife, or long, emphatic dissolves, as in music. Shallow story in Berri, shallow setting in Vecchiali. The same effect, the same search, the same fight: precise touches of reality in an artificial atmosphere, one that presents itself as such. Taking off from reality at all costs. Berri with the feeling of distance given by recording studios or, better, by wealth and luxury, inaccessibility; Vecchiali with the terrorist juxtaposition of two spaces, that of the real banlieue with its vacant lot and that of a house open to all winds, a real film studio installed in a fake house. We fall back on Minnellian litanies, ‘all the world’s a stage, all the stage is a world’. What to believe? And, above all: how long to believe it?

Nightmare of duration.

It is repetition that becomes intolerable in cinema. What are we to do with an hour and a half watching a film unfold when we know within a few minutes what it will be about, where it’s going, where it will end? Seeing a film becomes something different: accepting — or not accepting — variations on a theme as a possible replacement for a story, the beauty of effects as taking the place of characters; aestheticism becomes the subject of the film in its own right, its avowed and avowable raison d’être. Such is the case with C’est la vie: a stylized chatterbox talks on the phone, meets the caretaker of the H.L.M. housing project [7] where — so the viewer must pretend to believe — little daily dramas unfold; life, in other words. A well-imitated radio/TV host, another equally successful one, a man who doesn’t understand the chatterbox heroine, another who won’t understand her any better, misunderstandings sung, danced, filmed. In this case, we can’t interest ourselves in the fiction. In what, then? A: how to film what is onstage, how to stage this cinema, how to film the film? Problems for the artists, the painter, the stylist. Under these conditions, it is not surprising that we’re moved by the only sequence that is openly flat, stripped of any fictional impulse, purely decorative: a man leaves a woman, his suitcase falls open in the grass, and all we see is red — everything is red, the flowers, the clothes, everything, an incredible assortment of reds, a gradient, a score; unique, rare, abstract emotion: colors have replaced feelings, the characters have melted into the web of the film — it’s the very fabric itself that moves us. Abandoning for once, just once, the fictional futility that weighs heavily on him, Vecchiali discovers the only seriousness that matters to him, made up of authentic futility, proclaimed platitudes, total artifice — and why shouldn’t we be moved by the freely consented delirium of a filmmaker who assumes his role as a stylist? There comes a time, and with C’est la vie that time has come, when you have to make a choice, stop procrastinating, stop making the back-and-forth between artifice and reality a figure of style, a mask, a screen — and choose once and for all, commit yourself, expose yourself. Realist or delirious, flat or deep, the film must, at one moment or another, be what it is. It must coincide with something. The feeling of duration, of standing in place, of non-progression, never comes only from abstraction — which is without duration, atemporal — but from a bad blend, an approximate mixture: dressing reality in the clothes of the circus (or the operetta) eventually makes you sick of the operetta, of the circus, of realism — once all credibility is spent, all that remains is the feeling of time passing. A little vain, all the same.

Duration of the nightmare.

The same goes for Simsolo: a belated feature film after a few shorts that had carved out a genuine little space for themselves, and for him, on the border between artificiality and bad taste — a stage draped with derisory puppets disguised as tragedians, improbable heroes, fatal silhouettes. And now it has to be ninety minutes long: no problem, we’ll play the same record — but slowed down! The young amnesiac pianist will return in each shot, make the same gestures, stretch out the same silences: the gesticulation proper to a nervous, excessive, enthusiastic universe is transformed into slowness, mannerism, affectations; the talkative, sententious characters become self-indulgent tramps, interminable ramblers, exotic, provincial equivalents of Goodis’s hyper-American, hyper-marginal drunks — their obvious model. Crimes, passions, plots: everything becomes soft and poetic, neorealistically and clumsily French — sub-Carné. And at times — like in the red scene in C’est la vie, and one might almost say ‘by some miracle’ — Simsolo rediscovers the masked rigidity, the genuinely cheerful, self-assured falseness of his earlier films: the conspiratorial lovers kiss at the turn of a sequence — the camera uncovers the sudden frigidity of their embrace; an actor waxes poetic to excess, his eyes moist — but fortunately he is murdered, he lets out what’s inside him, does his number, at last; or a few words, murmured drily, by a young blond man flirting with a little girl who is too dark — no need to convince, to make it real; it’s enough to simply record the scene and its falseness is convincing. Moments devoid of all fictional heaviness, free from the constraints of the story and the imperatives of the script: freely consented, gratuitous fictional fluctuations. All this is to say that in this cinema/song (and this goes for Cauchemar as well, with its realistic old tune that fixes a dated atmosphere), as long as you’re doing it, you may as well play the game: it’s those moments of a loss of energy, a flight of meaning — purely musical, abstract moments — that alone succeed in introducing a filmic equivalent of the song we hum without realizing it — moments of emotion when we are indeed caught in the spell. When we forget the time.

It’s better to do away with rigid systems — sequences in continuity in Vecchiali, broken constructions in Berri and Simsolo: games with time — which constantly remind the viewer of the order of the fiction, of the rules of its unfolding: the unpleasant sensation of having before your eyes the carcass of a film, the skeleton of a story, the imperatives of a corpse. Cinema becomes old-fashioned, dated — it feels stale.

Give us stories from today!

Why are Berri, Simsolo and Vecchiali getting nowhere? Once again, it’s not the framework they’ve chosen that is the problem, it’s its sister: the morality. Today, we can no longer use codes to elbow our way through; gratuitously appropriate the stylistic achievements and content of old films, stir it all together and serve the sauce — retro, indigestible, muddled. You have to put your own person into it, your body as the filmmaker involved, yourself. If Treilhou in Simone Barbès and Godard in Sauve qui peut, with two films built on the same patterns as the ones we are discussing here, with songs or their equivalents, that is to say repetitions, musical reprises, breaks — if they succeed completely in convincing, it’s not because they are more talented, brilliant or intelligent: they speak about what they know, what they have seen and experienced themselves — and, in so doing, they inject some autobiography into their films, someone saying ‘I’. A story is told and heard.

There are reasons for this: Treilhou is not a cinephile — women never are; the past doesn’t obscure the present; it doesn’t cover it with its drippings. No citations. Godard — this has always been his strength — insists on the burning immediacy of the present, everyday life at its closest: lighting, clothing, makeup, even framing, everything comes from today, from the media’s representation of our present, of ourselves. Hence that very ‘contemporary’ feeling that the eighties are there in his films and nowhere else to be found. Two direct films in the middle of a confused, sophisticated, hypocritical French production. A desert of proper, well-mannered, impersonal cinema.

What’s unfortunate is that Vecchiali, Simsolo and Berri weren’t always like this; they were once badly behaved, dirty, personal, creative. Why do they now seem to have joined this desert of French cinema, an overpopulated desert at that? It’s because they are in between: between Scylla and Charybdis, between zones, between stools; nowhere; lost. In this no man’s land where you commission your own little story from yourself, which must be both personal and polished, original and popular, commercial and artistic. The intellectual cogitations of those with time to waste: without hindsight, in the wasteland of moribund ideologies, they craft cold neo-contemporary tales, sad romances, mechanical ballets. With the same — heavy, eternal, styleless — way of filming: classical frontality, lengthiness, boredom. A total lack of invention: relying on the old recipes, the tired phantoms of an outdated, worn-out classicism.

At some point or another, a choice will have to be made. To come to terms, for example, with one’s own superficiality: why not imagine other durations, less rigid fictional frameworks — why not make the most of your freedom as an aesthete, of your vacancy? Or, on the contrary, to create something new, something intense: to really work on framing, editing, fragmentation. In any case, to tune your existence to the film — as you tune an instrument so that it sounds right, so that you can make music with it.

French cinema is dying under the weight of sad conventions and stereotyped ideas about its audience that are imaginary, useless. It is dying from its false audacity, its limp ‘scoops’, its narrow particularisms. Above all: it never dares to be, without any detours, what it is. Nothing more than that. Nothing else. That alone would be enough: sharpness, flatness, density; a little real reflection on our lives; a bit of insouciance, in form as well as content; all the self-indulgence in the world, if you like, as long as the risk of being recognized, pinned down, is truly taken. Without a guilty conscience or excessive distance. A direct cinema, finally.

Cahiers du cinéma, 319, January 1981, pp. 47–50.

‘You reproach me for my champagne?’

—Hélène Surgère in Femmes femmes

‘Curdled’ messieurs of cinema,

There is something sinister (the absence of seriousness) and moving (the permanence of error) in your relationship with French cinema. There is above all this cowardice of impotence that translates into the need for a hodgepodge, an elegant solution to avoid in-depth labor.

A hodgepodge that arrives rather late in relation to the positions of dominant criticism in general, and of distributors in particular (…).

A hodgepodge which I do not want to sacrifice.

It is Skorecki I am attacking today.

Naturally, I’m speaking on my own behalf. I reject the (hilarious) attempt at assimilation through which he wants to imprison me and my comrades… I recognize that he has taken some precautions, and that really is the worst part, because, that way, he does with his ‘article’ what he reproaches our films for.

Literally and figuratively, I do not feel absent from my films.

Doubting my sincerity seems to me resolutely futile. It would be better to investigate the importance of sincerity in cinema. What proof, and of what? See Godard on the one hand and Costa-Gavras on the other. As far as I’m concerned, I have a rule, a light one, of walking side by side with my characters, of remaining on their level. I am often reproached for this. I freely accept this: in fact, it corresponds to a risk I take.

Afterwards, the classic modesty–immodesty game calls the tune, willy-nilly. I think these back-and-forths enrich the relationship to spectacle; in any case, I like to submit to it, and that is no one’s business but mine.

The Family? Do we have to remind you that Saviange is the brunette and Surgère the blond? Tough luck, Saviange is not part of C’est la vie…

Don’t quibble. Examples of filmmakers with muses, or of loyal filmmakers, abound. As they are among the greatest, I will not talk about them.

To work with people you know, you need much more vigilance. If you think it’s a safety measure, that’s just you not respecting others. I mean that you believe they are immutable.

As for ‘the humanity of relationships’ with the ‘family’, Jean-Claude Biette among others — a good witness — must be rolling on the floor laughing, reading what Skorecki says!

Another received idea: you have to speak about what you know. If that isn’t running in circles! Learning to make a film, discovering, or simply searching, going to meet a universe, an idea, a problem, a person, is subject to a practice and a morality that are much more alive.

Above all, I would have done without the Virtue–Courage couplet: courage consists in doing with dignity what one does not want to do, and virtue in drawing no profit from it. Nothing to do with the objectives of Diagonale.

Moreover, the formulation reveals a crass ignorance of the system and its function. It is not Diagonale that can only afford Simone Barbès, but Marie-Claude Treilhou who can only afford Diagonale. If, tomorrow, we hired a guy like Polanski (it’s obviously out of the question, but not for economic reasons), we would also have the money that goes with it. I assure you that we would produce differently.

The style… Skorecki probably goes to the cinema whenever his will ‘sings’… [8] Is that normal? It’s not, he draws hasty conclusions. These cookie-cutter, poorly supported, incoherent conclusions are published in a magazine, and it becomes flat out harmful — for said magazine, of course… It must be said that Rivette and Rohmer were stricter about the finish of articles…

To say, for example, that CLV is filmed frontally is simply to lie. The entire scenography is based on depth of field, on the fiction-space that plays with the real as well as the real space (the window) that plays on and plays with fiction.

Skorecki has a weakness for red. Okay. But it’s his problem to not see the blue sequence, the yellow sequence, the white sequence… which function like the red one. It’s true that it comes last. Either Skorecki is slow, very slow, or he has dozed off before then.

Besides, the fact that there are other color-sequences is not important in itself. To see the relationships among them, or what they tend towards, would be to do criticism. To remark that Ginette takes it all in the end would be to follow the story. Skorecki does neither.

Yes, there is coincidence in CLV, or, as I prefer to say, convergence: convergence of the media, staged by the film of the story — media which itself is tainted by the same vices it reveals. Media avowed and risked, which Ginette flees in fine (the shot amid the end titles), while taking with her the colors of time, an indication that she has perhaps become media herself.

When we’re bored, we’re bored, it’s not a fault. No use boring others by resorting to general ideas to justify one’s boredom. Skorecki’s boredom, distinguished as it may be, concerns only himself. He should sort it out, instead of theorizing. Not everyone can be Godard: Rivette–Verneuil’s coup [9] is outdated, stale, worn out…

As for the dense fiction he claims, he can go rediscover it by rewatching Le Dernier métro or — why not? — Corps à cœur. But, for fiction to fiction, one has to be a viewer, someone who, evidently, Skorecki is not.

He should let us make our choices without putting our intentions on trial. As much as I can, I use my freedom to investigate cinema by telling stories. It’s a dialogue of doubt, but also a dialogue of love, which can definitely do without a witness.

Now we arrive at direct cinema! What platitude: Godard makes direct cinema, like we once said Bresson did Jansenism! There is no one who is more mannered, more aestheticizing than Godard: it is in the admirable discrepancy between the realism of his offscreen and the affectation of his frame and his lighting that his dialectic is nourished… In my view, anyway… Skorecki should leave the ‘rules’ to the CNC.

One can be sadistic like Pialat, masochistic like Godard, cautious like Truffaut, superficially superficial like Biette, affected like Chabrol, innocent like Treilhou, subservient like Eustache, drifting like Téchiné, mischievous like Rohmer, conflicted like Simsolo, attentive like Rivette, perverse like Demy, ‘direct’ like Rouch, elegant like Pollet, nostalgic like Guiguet, scatterbrained like Moullet, pure and hard like Blain, devious like Mocky, heartbroken-breaking [10] like Bresson, inspired like Straub, [11] if love for cinema and seriousness of labor count. The rest is a matter of ‘quality’, which does not concern me.

What does concern me, however, is the moral lesson of poor Skorecki. Parable: if famine threatens you, die of hunger rather than not having a full meal, with cheese and dessert.

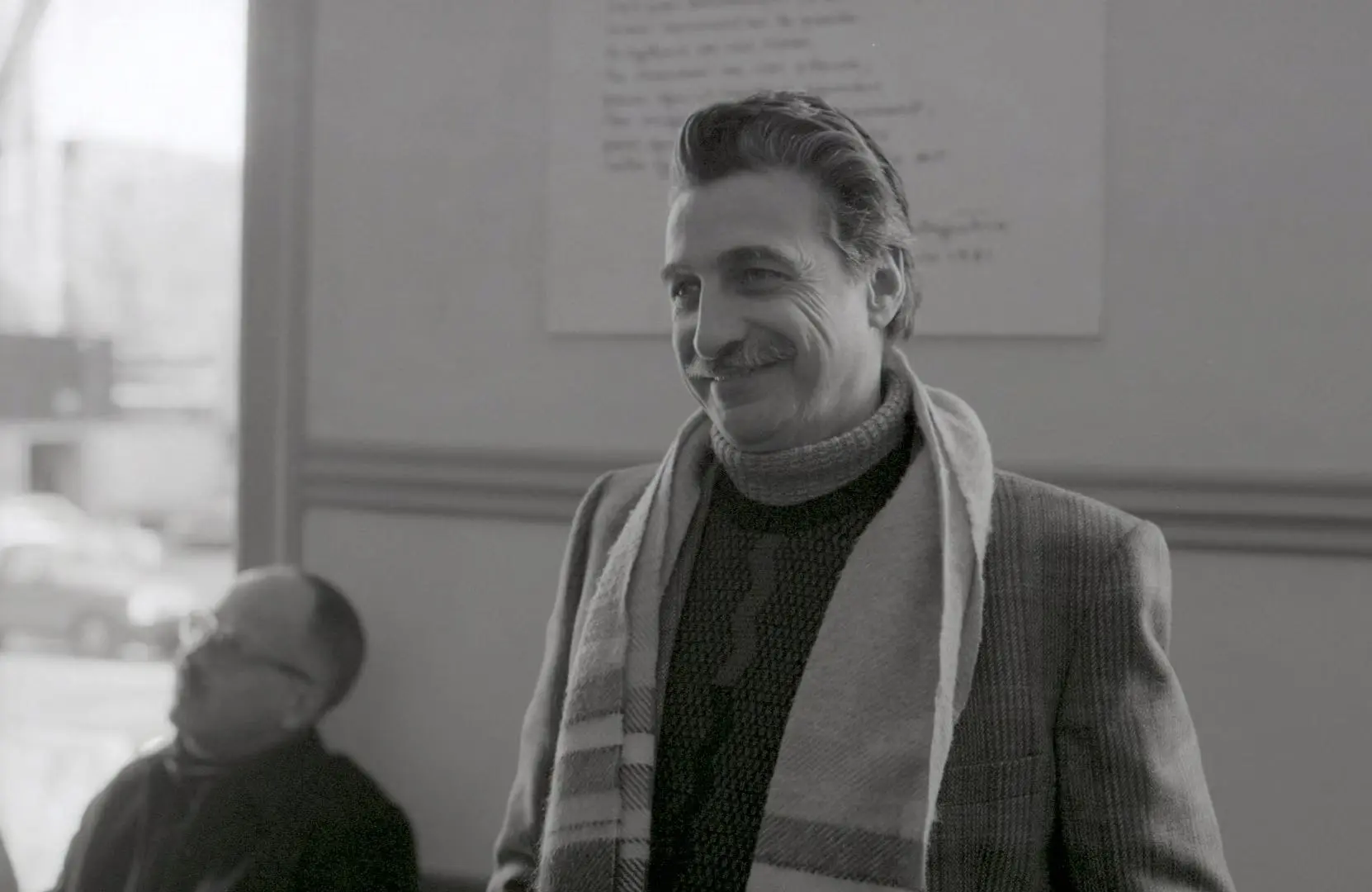

C'est la Vie ! (Paul Vecchiali, 1980)

If I weren’t afraid of being taken à la lettre, I would say this: the time is long gone when critics of cinema, apparently to promote themselves and say ‘watch out, it is us who are important’, invented the politique des auteurs. There are no more authors, only films, I repeat, and that’s a good thing. From here on, until filmmakers, lucidly desperate at no longer being able to exercise this phantom author function, start making films to signify that ‘we are the critics of society, the only ones able to proclaim something just regarding cinema and the world’, there is but one step — and a quick one. And there is no response to that. Just some clarifications, no doubt rendered necessary by the vagueness of my text.

1) From my own perspective (there are only films: a disillusioned perspective, needless to say), I don’t just have a problem with French cinema and its specific defects: there is a general crisis in cinematic creation. I can’t do anything about it, that’s how it is. And I don’t have a model, a miraculous recipe, a ‘great positive’ to propose. I’m waiting.

2) Hindsight is difficult today, for filmmakers as well as critics, because there is only one cinema, one unique model, which makes any comparison practically impossible. Twenty years ago, films were being made that were badly put together, badly filmed, morally condemnable, etc. Today, everything, from Super 8 to Super 70, spanning all intermediary stages and all possible creators, is filmed almost the same way: we can call it frontality, classicism, fluidity — one single image for all cinema. A conception of cinematographic art has won a victory that is, grosso modo, the one for which Cahiers fought: today any filmmaker can make a feeble Hawks. And he doesn’t hold back.

3) Some glimmers, some hope from those who experiment in honest and straightforward commerce: promotional films lasting a few minutes for rock or pop bands, commercials lasting a few seconds; there at least we are searching, we are creating something new. But as far as fiction feature films go…

4) Femmes femmes is an extraordinary, unique, very dark film.

5) If Godard, with Sauve qui peut, seems so contemporary, so modern, it’s not that he films differently than others. No, he films in the same way. Simply: he doesn’t say the same things and he hangs out in unclean places. And he films and records them with a professional conscience that is higher than most of his comrades: as if to make them ashamed. But it’s been a long time, in French cinema, since we were ashamed of anything.

Cahiers du cinéma, 320, February 1981, pp. 65–66.

Notes

See Vecchiali, Le cinéma français: Émois et moi — Tome 2: Accomplissements (Éditions Libre & Solidaire, 2022), pp. 45–47; Roland Hélié, ‘Entretien avec Paul Vecchiali’, Fiches du cinéma, 4 June 2018, <https://www.fichesducinema.com/2018/06/entretien-avec-paul-vecchiali/>.

Translator’s note: referring to the lyrics of Claude Nougaro’s ‘Une petite fille’ (1969).

Translator’s’ note: a character in Simon’s song, named after the protagonist of Pierrot le fou (Ferdinand Griffon) and the film’s director (Jean-Luc Godard). The titular Juliette is an homage to Juliet Berto, particularly her character in La Chinoise.

Translators’ note: possibly alluding to the protagonist of C’est la vie ! failing to answer her phone calls.

Translator’s note: Skorecki’s two proposals for merging Berri’s and Vecchiali’s titles.

Translator’s note: Cauchemar — a reference to the title of Simsolo’s film.

Translator’s note: Habitation à loyer modéré, a form of low-income housing in France.

Translator’s note: To mock the focal point of Skorecki’s attack, Vecchiali puts ‘chante’ between scare quotes to pun on the verb’s literal meaning in the otherwise idiomatic ‘quand ça lui chante’, usually translated as ‘whenever it pleases him’ or ‘whenever he wants’.

Translator’s note: perhaps a reference to Rivette becoming the editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinéma in 1963; Henri Verneuil’s Mélodie en sous-sol, a heist film, was released in the same year.

Translator’s note: Vecchiali seems to be combining the past participle and the adjective form of the verb déchirer into déchiré-rant.

…and these are only a few in French cinemas.