A friend of Ugo Betti, assistant to Rossellini, [1] kickstarted by De Sica, admired by Tavernier, one of the most singular, most gifted, and most neglected filmmakers in the history of Italian cinema passed away on December 14, 1998, at the age of 84. As is usually the case, he owed his relative notoriety to the least engrossing fraction of his filmography: the five or six big-budget pepla he shot between 1958 and 1961 (La rivolta dei gladiatori, Le legioni di Cleopatra, Messalina Venere Imperatrice, La vendetta di Ercole, Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide). Even if — by their plastic qualities, by certain moments of grace in their mise en scène, by the humor or irony sprinkled over them, which introduce between the spectator and the spectacle a distance which finally isn’t Brechtian but rather prophylactic — these films stand high above others of the same genre, the best Cottafavi can be found before and after this period: in the black and white, more exuberant than color, of melodramas and swashbucklers such as Il boia di Lilla, Il cavaliere di Maison Rouge and I piombi di Venezia, and even in the admirable Fiamma che non si spegne, a war film that provoked quite a polemic at the Venice Film Festival in 1949.

But his masterpiece remains, without a doubt, I cento cavalieri, the last film he shot for the big screen (1964, released in France in 1965). In it, we may find all the tendencies of his inspiration gathered in a truly Shakespearian symphonic composition: the tragic, the burlesque, the haughtiness in relation to the story, the sense of history, the mastery of pure action, the plastic experimentation, the cruelty, the poetry.

After his swan song, Cottafavi, to whom producers in vain offered golden opportunities to go back to directing mythological films, saw all the projects he cherished sink: Il deserto dei tartari, Bernanos’ Un crime and Sous le soleil de Satan, Adrienne Mesurat, Leonardo Sciascia’s Il giorno della civetta, and also two original stories written by himself.

From then on, he dedicated himself to television and even became, for a while, president of RAI’s directors. Bad as it may be, the small screen allowed him nevertheless to feed his true ambitions, at a time when television hadn’t yet prostituted itself to audience ratings.

Besides two or three articles published in the Cahiers du cinéma, the origins of the discovery of his work, first in France and then, later, in his own country, date back to a special issue of Présence du cinéma published December 1961. This issue, wholly devoted to Cottafavi, notably included a long and wonderful interview that provoked nothing less than a shock... so much so that some (notably the critic Louis Marcorelles) thought it was apocryphal. From then on, his name and the name of his films found their place in the cinema dictionaries. The Cinémathèque Française organized a retrospective of his films in the 1980s. Only the dirtiest dogs of criticism stubbornly refused to acknowledge him or to see in him anything more than a sculptor of Greco-Roman cardboard cutouts.

Let us quote the filmmaker, and his eulogy of silence:

In the first place, one must renounce that which, by describing the character, separates us from him. [...] When we go beyond a certain emotional charge, when this emotion must invade the spectator’s interiority, it must invade him at the same time it invades the character’s interiority. Words create a distance, a subject-object situation. Whereas silences already establish an identification. [2]

We would not be capable of more precisely rejecting the very notion of ‘distanciation’ (Brecht’s famous ‘V-effekt’), nor of better placing ourselves in the direct lineage of Aristotle. Cottafavi was, as much as Preminger, a dramatist of fascination.

(December 1998)

From L’Écran Éblouissant — Voyages en Cinéphilie, 1958-2010

(Presses Universitaires de France, 2011), pp. 189–191.

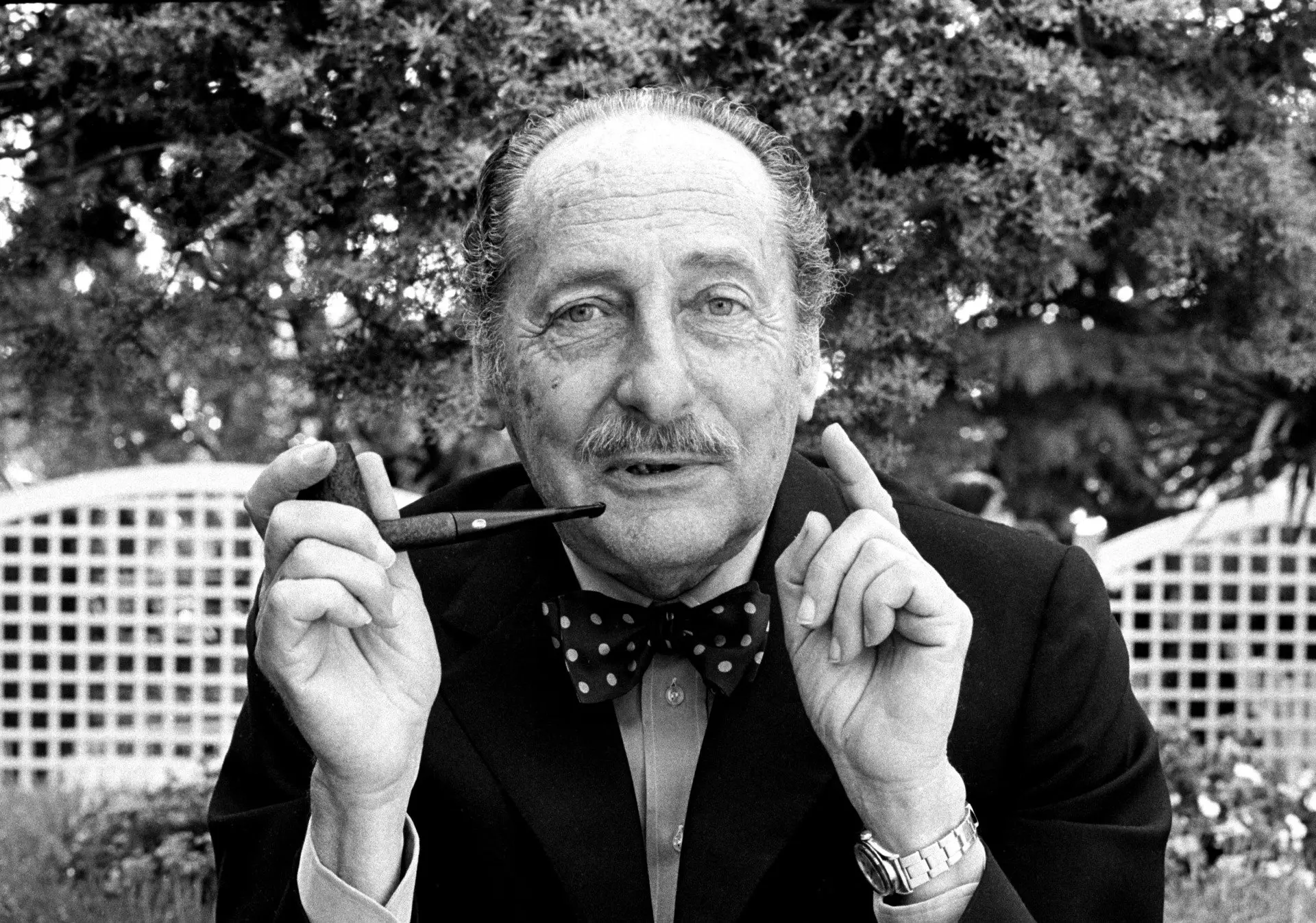

Vittorio Cottafavi at the 1985 Cannes Film Festival

Notes

Translator’s note: Mourlet is probably confused; we could find no reference of Cottafavi ever having worked with Rossellini.

Michel Mourlet and Paul Agde, ‘Entretien avec Vittorio Cottafavi’, Présence du cinéma, 9 (December 1961)pp. 5–28. An English translation of this interview is available at https://theluckystarfilm.net/2025/03/12/translation-corner-vittorio-cottafavi-in-presence-du-cinema/.