There is a side of old France to Paul Vecchiali. This alumnus of the École polytechnique has always managed his production companies (Les Films de Gion, Unité trois, Diagonale) as a good father of the family, [1] with love, rigor and meticulousness, like Truffaut, Rohmer, Tavernier, Varda or I, as opposed to most, who do not fear adventurous bets or risks of bankruptcy. This thoroughgoing traditionalism is somewhat contradicted by a humane and generous gaze on the world of homosexuals.

His reactionary, right-wing, even pot-au-feu [2] side translates, in particular, to a great attention to family and parents. In this regard, I don’t see anyone who can be compared to him other than Tavernier (Daddy nostalgie, L’Horloger de Saint-Paul), the important difference being that Tavernier situates himself on a completely opposite political horizon.

Vecchiali is, I believe, the only filmmaker in the world who has dedicated a film to his mother (En haut des marches) and another to his father (Maladie). The two are furthermore judiciously paired on the same disc in the beautiful boxset Antiprod has dedicated to Vecchiali. An apparently unequal treatment, since the former is a feature-length fiction film and the latter a short documentary, but this latter has the advantage of a greater rigor, a more assertive emotional and artistic power.

This is an unusual artistic orientation, compared to the national cultural context (Gide’s ‘Family, I hate you’ [3] ) and compared to our cinema, which tends rather to show the fracture between generations (Truffaut, Chabrol, Becker, Pialat) or to omit the previous generation (Rohmer, Godard, Rivette, Resnais).

Paul Vecchiali, eighteen years after the death of his father Charles, found his diary, which recounts the progression of his illness from 1952 until his death in 1959.

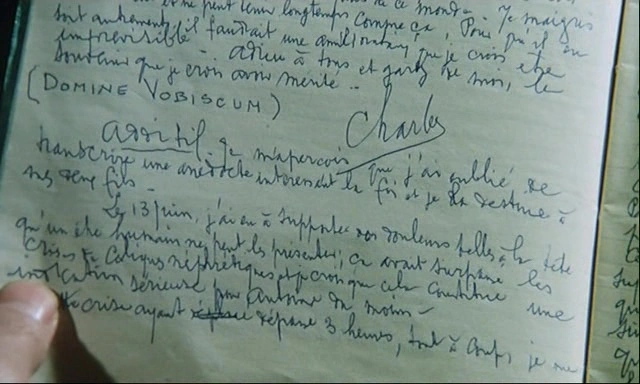

He then filmed this journal kept in a notebook. The entries it contains are succinct, precise. They are of a quasi-military rigor. [4] The deceased was a captain, for that matter. And emotion arises from this contrast between the dryness of the filmed text, accentuated by the neutral tone of the narrator, and all that is dramatic in it. We really have the impression of an impregnable ill (we are warned from the start of the fatal outcome) which progresses relentlessly despite brief lulls. It all begins with asthma attacks, which seem to have entailed much more serious afflictions, since Captain Vecchiali was going to die of cancer. Unless there was a chance coincidence.

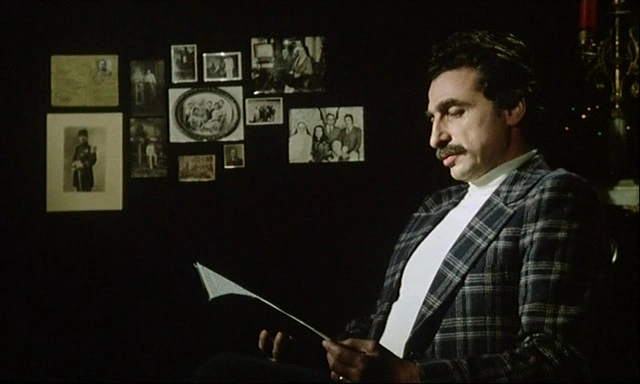

The text is read, with a few amendments, by Paul Vecchiali in a quite Bressonian manner. We are further reminded of the writing/voice doubling in Journal d’un curé de campagne. The spectator reads the writing more quickly than the narrator. This means that, often, to maintain the asynchronicity, Vecchiali begins to read from the fourth or fifth line of the text. The spectator must then make an effort to try to find in the notebook the text they have just heard. This increases their participation in the film.

Maladie (Paul Vecchiali, 1978)

Towards the end, the writing, quite readable until then, becomes broken, clumsy. Guided by a few effects of facial metamorphosis due to the illness, which are revealed by a striking cut [5] montage, we become aware that Charles is approaching his end, which he himself well realizes. Paul Vecchiali adds that his father recounts his dialogue with God (he claims to have heard Him), that he identified life as a passage and thought that eternity constituted true life.

We find here the itinerant state of the end of lives. Charles Vecchiali wanders from Toulon to La Roquebrussanne, to Le Luc and to Montpellier: very ill people are constantly in a vain — often contradictory — search for a place, or a hospital where they might feel better…

The resemblance between Charles and Paul remains striking. The shared moustache has a lot to do with it. The family photos are in black and white, as is an image of Paul, a photo it seems. But suddenly, it comes to life. [6] He wanted for a moment to situate himself on the same level as his father. We think for a moment that we see Charles’s fingers, but they are Paul’s. And, what’s more, Paul speaks in the first person in place of the father, as if he wanted to prolong his existence.

This is surprising in Vecchiali’s oeuvre, where protagonists are mostly feminine and maternal (only women in Femmes femmes, Danielle Darrieux in En haut des marches [7] ).

We thus find here, for the most part, color shots of Paul Vecchiali speaking, black and white shots of family photos, and shots of the notebook, sometimes with — as if by superimposition — certain photos. But those are probably not superimpositions: they would have been too expensive given the film’s budget. These are mirror effects that reflect the somewhat evanescent image of the photo onto the pages of the notebook.

Maladie is indeed a no budget film. [8] Vecchiali claims to have shot it in two hours. This annoys me: I have spent more time writing this text. We have here the proof that one can achieve touching, moving masterpieces like Maladie with nothing. It was Maladie which motivated me to shoot short films again whenever I wanted to. In 1978, directors of feature-length films felt devalued if they returned to short films.

This, I believe, is the first time a filmmaker has devoted all or part of his film to his illness (Charles being here the alter ego of Paul). Since then, there have been Nick’s Movie (Nicholas Ray, Wim Wenders, 1979), Caro diario (Moretti, 1993), Laatse woorden, mijn zusje Joke (Van der Keuken, 1988), Le Fil de ma vie (Lionel Legros, 2002), L’Insaississable image (Hanoun, 2007). The origin of this lament about illness can probably be found, in fact, in Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (Visconti, 1975) and throughout Dwoskin’s oeuvre. [9] The filmmaker seeks not to die in order to be able to finish his film.

Some will argue that everything was already in the diary of Charles Vecchiali. Paul did not have much to do. Perhaps. But it’s the result that counts, no matter where it comes from. It takes a lot of tact and sensitivity to translate this diary into film without betraying it.

And Maladie cuts across an entire modern cinema made of writing and speech, which is that of Bresson and Straub.

Bref, 88, July 2009, p.34.

Notes

Translator’s note: Moullet is evoking at once the literal and legal senses of the expression ‘en bon père de famille’, the latter of which is equivalent to ‘with due diligence’ in English.

Translator’s note: Figuratively, this term describes someone who is too occupied with household affairs and would rather stay in than go out.

Translator’s note: From Book IV of André Gide, Les Nourritures terrestres (Mercure de France, 1897). The sentence in the original text has ‘family’ in the plural; Moullet cites it in the singular.

In this objective context, the very rare adjectives that mention pain take on a considerable importance.

Translator’s note: in English in the French text.

Vecchiali, in a questionable manner, deceives us for a moment: we think we are dealing with a photo of the doctor, when in fact it is Charles.

Which is really its twin film: it begins precisely with family photos.

Translator’s note: in English in the French text.

Translator’s note: Titles not originally in French have replaced the French ones Moullet uses.