Gaël Teicher: All three of you were credited as co-authors of Vecchialli’s films: Bonjour la langue for Pascal Cervo, Trous de mémoire for Françoise Lebrun, and La Machine for Jean-Christophe Bouvet — the whole final section of that film is your text. [1] What does it mean for an actor to be a co-author with a director, and with this director specifically? How did that come about? We know that there were improvisations, but that’s not all… Could you each recount the adventure of co-authoring like this, and, for Françoise and Pascal, of playing opposite the director-actor as your only partner in those respective films?

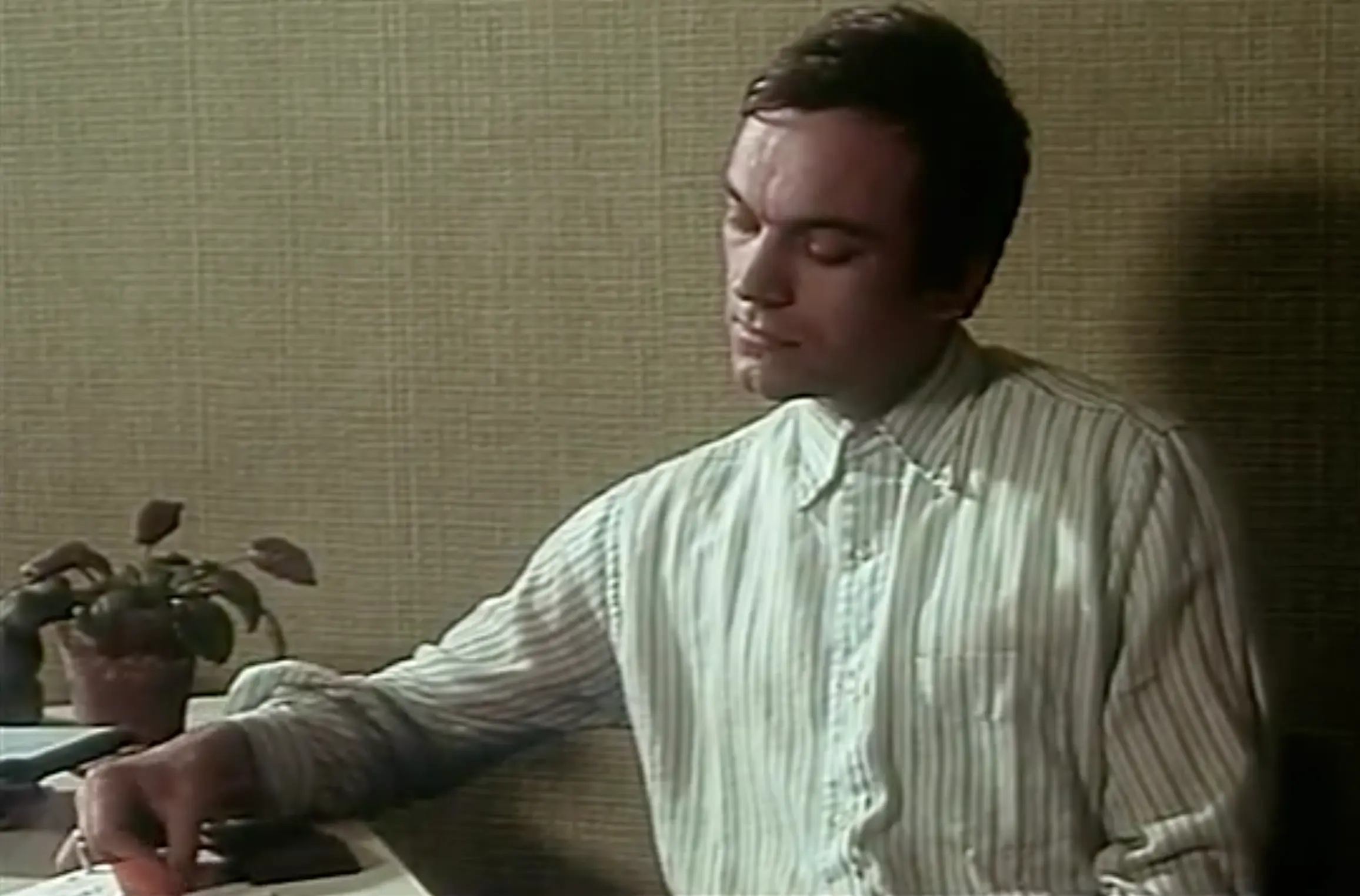

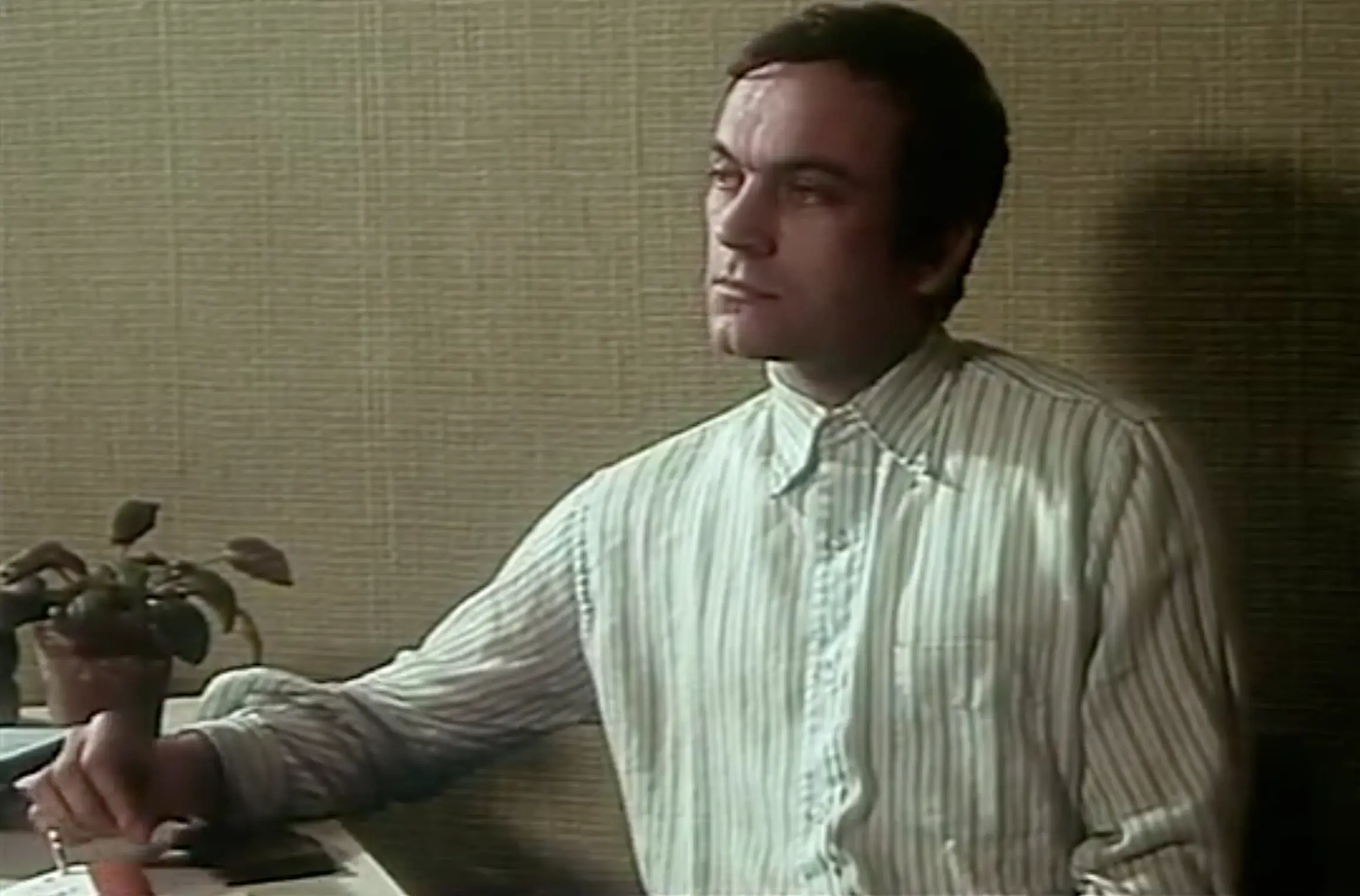

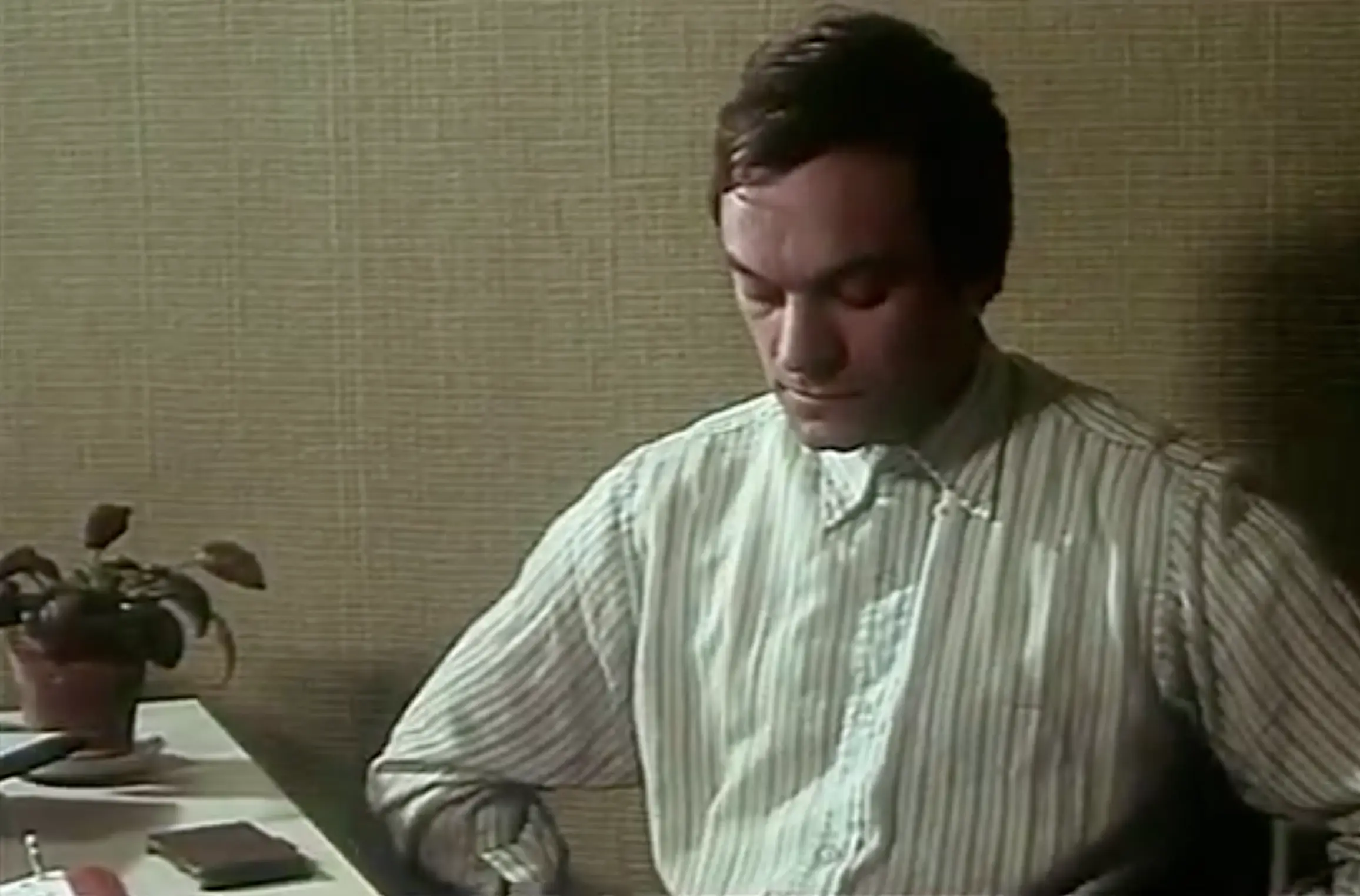

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: La Machine was a film that I brought to Paul. A twenty-one-year-old boy had been executed in France, Christian Ranucci, one of the last to be guillotined, and I was so sickened by it — I campaigned against the death penalty at that time — that I talked about it with Paul Vechialli, who said to me: ‘I’m off to Venice to film the festival with Jean-Claude Biette, we’ll be back at the end of the summer.’ While waiting for him to return, I did some investigation: I contacted Ranucci’s lawyers, who gave me access to his dossier, and I did some work as a journalist-sociologist-psychoanalyst. I did a lot of research, spending my summer at the BnF [Bibliothèque nationale de France], and gathered an enormous amount of information. When Paul returned from Venice and saw all this work, this dossier, he said: ‘OK, we’ll make the film.’ So a part of the script had already been written through that journalistic work. After that, I wrote my dialogues, those that I wanted to have. I don’t think of myself as a comédien, but as an actor [acteur], by which I mean that I like to make the character come to me, I like to write the character, whereas I’m extremely lazy when it comes to entering into the universe of others, taking an interest in the text, etc. That’s painful for me, unless I can write my own text. That can be done in collaboration, which was sort of the case with Paul, even though there are whole sequences where he let me write my own text. Notably the end, where I gave the floor [la parole] to Pierre Lentier, and thus ultimately to a boy like Christian Ranucci, who had killed an eight-year-old girl and who, at the moment at the end of the trial in which he was asked if he had anything to add, as is standard, said nothing and had nothing to say. At that point, in the fiction, I give him the floor. And that final speech concerned the ‘why’: he describes his pedophilic desire — his crime, which came from sexual compulsion — and his fear of detection. Ranucci had been surprised in the woods and had killed the girl because she had started to cry out, to struggle. There were also some improvised scenes, notably the one with the psychoanalyst, where I played opposite a real psychoanalyst. The sequence lasts five minutes, in which I don’t speak much, I rather make gestures, and amuse myself with the stationery. I was told ‘Oh, that’s very Actors Studio, that part!’ It’s possible… So that was the collaboration between Paul and I. In the credits he put me down as ‘co-dialogist’ rather than ‘co-writer’, which was fine with me.

Françoise Lebrun: I participated in eight of Paul’s films. Trous de mémoire was completely improvised, apart from two specific points that had to be included. It was a lot of fun, and Paul surprised me with his interventions. I had a certain power, however, which was to decide when we would stop. It was a time of innocence, the shoot happened just like that, almost from one day to the next, on a beautiful day, a little chilly, but sunny. There was a piece of luck, something very luminous in this story, owing to the constraint of the ten minute reels: Strouvé’s wife [2] was there with a white handkerchief, and she would make a sign to let us know that we had to find a punchline because we were getting to the end of the reel. We didn't know where we were going, but I felt a little reassured after the first reel: ‘Okay, great, we’ve already got enough for a short, so we didn’t ask the crew to come here at five in the morning for nothing!’ That put me at ease a bit, and I said ‘We can go on like that.’ For Fugue en sol mineur, which is a short, Paul locked me in a room to write the script because I didn’t know what to do. Then, for À vot’ bon cœur, this story about the murder of the CNC [3] people, there were things written down, a lot of them, in terms of the general plot and the dramaturgy, and Paul had prepared a lot of things that really came from him. In Le Cancre, part of it was written, but the last line just came like that. We were looking for the famous marguerite [daisy] and he said to me, ‘Do you know where Marguerite is?’ And I replied spontaneously, ‘She's in the fields.’ There was this openness with Paul, this possibility of following both his path and my own at the same time. It was quite joyful!

Gaël Teicher: You said that there were three points to adhere to in Trous de mémoire. What were they? What did you know prior to the first take?

Françoise Lebrun: All I knew was that I was being summoned to Versailles and that we would shoot something with stock leftover from some institutional film that Paul had shot with who-knows-which-water-company. We hadn’t really spoken about the project, but he wrote me a letter that I received by post and which I had to open in the film. And that I had the possibility to pull the alarm and say ‘We stop there.’ There you go, those were the three points.

Trous de mémoire (Paul Vecchiali, 1985)

Damien Bertrand: What you’re describing there is an idea that musicians have, when in their improvisations they set ‘meeting points [« points de rendez-vous »]’: if something is expressed at a moment T in a soloist’s playing, that indicates to the other players that the piece is going to change gear, or switch to a more collective and simultaneous mode of expression. In music as in cinema, that requires complicity between the actor and the director. With respect to that final ‘meeting point’, did he leave you to choose where it landed, whether it ended well or not?

Françoise Lebrun: I haven’t watched the film in a long time… But given that I was never in the position to say yes or no, I had to take the middle road in the end, neither yes or no. The idea was a couple that had separated and who met again to search for something, and there was the possibility that the couple got back together, or not. Myself, I’m more the kind to say ‘Nah, let it be, it’s not worth it.’

Gaël Teicher: That basis, of a separated couple who meet again, you knew it in advance?

Françoise Lebrun: That part, yes. But the starting point was really the idea of searching for something. In the letter that he sent me, he said that he needed me because he was searching for something and he couldn’t find it, a memory, a song. Of course it wasn’t only about the song, it was about meeting me so we could get back together. But from the moment when I would sing the song, that was the signal that we were getting to the end. That we had reached the last possible point of these confrontations.

Damien Bertrand: I had remembered there being lots of sequence shots and was very surprised rewatching it: there are a lot of cuts in the film. Even beside the tree, even when you’re not moving in the shots, the camera changes position. Yet one is left with the feeling of a film in sequence shots. No doubt because the real duration, the duration as it is lived, is restored with such a continuous breath that one totally forgets the mechanical apparatus which allows it to be recorded.

Pascale Bodet: Since it was an improvised film, didn’t Vecchiali do it in only one take?

Françoise Lebrun: Yes, absolutely.

Pascal Cervo: Paul particularly loved one scene that we had improvised together in Le Cancre. We’re having breakfast together, and he talks to me while I play with my tablet. It was probably that scene which gave him the idea that we should improvise together in Bonjour la langue. For me that was the culmination of a working relationship that had started with Faux accords and with a monologue of twenty pages, written in Paul’s particular language, a bit arduous; we shot that in one take, twenty minutes long. With Bonjour la langue there was no longer any text, but, as with Françoise on Trous de mémoire, there was a framework. Paul spoke about the film for a year. The first thing he sent me was a découpage: one day, three places, three part, and the idea of a confrontation in the first part, that the second part would be reconciliation, and the part would be the ‘point of interrogation’. Three places: the villa, the restaurant, a garden. That was respected. We talked on the telephone and didn’t agree. He imagined a dispute between a father and a son, and I absolutely didn’t want a settling of scores. I dragged my feet and said ‘But no, Paul, we have to find a different idea!’ I could play a journalist who comes to interview you… He called me back and said ‘No, the father and the son is good, we’ll do the son from Le Cancre!’ He loved that, picking the same characters back up, continuity. Everything I hate! For me the characters in a film belong to it and afterwards I don’t want to hear about them any more. So I said to him ‘No, we’re not going to do Le Cancre again!’ One day, he called me up and said ‘Maybe the father and the son isn’t good, maybe it should be you and me!’ ‘Of course, Paul, we can do it all at once, you and me, father and son, mix in the journalist and the director, it will be fine!’ So in short, we had discussions on the telephone, and he won. He stayed fixated on the return of the son — the initial title for the project was even Le Retour. It took us a long time to get around to shooting it. Then everything accelerated after Godard died: all of a sudden he rang me up, ‘That’s it, I’ve got the title: Bonjour la langue!’, and we shot it three weeks or a month after that. I was apprehensive about the improvisation. Not because I don’t like to do it, but I couldn’t stop nagging Paul: ‘We still need to discuss things, set a framework, some reference points…’ I was wary of how easy it is to lapse into chitchat when improvising. Paul told me ‘Right, right, you come a day in advance and we’ll discuss it all.’ So we found ourselves there the day before filming, and he was already very weak, he slept basically the whole day, and I was left alone with my little piece of paper, telling myself stories. All he said to me was ‘You really have to chew me out, I really want you to give me a hard time.’ I tried to reflect on how to reprimand him without getting into a full-on settling of scores. As for constraints, the day I arrived he asked me to learn one of his poems, ‘C’est l’hiver’. I could recite it whenever I wanted to. Just as we were about to start shooting, Paul told me that he would like us to drop the titles of Godard’s films into our exchanges. He had also decided that my character would be called Jean-Luc.

Françoise Lebrun: Which titles did you manage to drop in?

Pascal Cervo: Hélas pour moi. Le Petit Soldat… Something related to Masculin/Féminin, not the title, but the question that Chantal Goya poses to Jean-Pierre Léaud: what is the center of the world for you? Concerning the homage to Godard, I only once asked Paul, over the telephone: ‘What’s the difference between le langage and la langue?’ Paul dodged the question. I sensed that he didn’t want us to address that subject in the improvisation.

Damien Bertrand: What was it like to be a comédien, or an actor [acteur], for Paul Vecchiali, having started out as viewers of Paul Vecchiali’s films? Seeing as each of you came in at different moments in his cinema, I imagine that it didn’t necessarily resonate in the same way?

Pascal Cervo: In general, I feel like I was a more docile actor. I listened more. I had first admired Paul’s films, before working with him. So I was more respectful of his instructions. That total respect for what he wanted, for his text, for his ideas for costumes or for instructions, which I sometimes disliked, initially made me more timid, but over the course of the films we made together I allowed myself to question things. For sure Paul pushed me, helped me grow.

Nuits blanches sur la jetée (Paul Vecchiali, 2014)

Françoise Lebrun: With me, it was always affectionate. I hadn’t seen many of his films. Les Roses de la vie, which I liked very much when I was at Science Po — I like to see films that represent ageing in cinema. When I say ‘affectionate’, I mean that I never really felt like an ‘actress’ with Paul, it was more something of a shared project. My first film with him, En haut des marches, had been very complicated for me. With La Maman et la Putain, there had been these long sequence shots where we didn’t move much, whereas with Paul’s sequence shots, you had to take five steps, say three words, go back to the other side, turn your head to the left… That was very difficult. Trous de mémoire, coming after that, was freedom, lightness.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: It was Jean-Claude Guiguet who introduced me to Vecchiali, who was looking for actors for Change pas de main, actors who could speak Shakespeare with a dick in their mouth. He had found Myriam Méziéres and me, amongst the select few who could do that… Before introducing me to Vecchiali, Guiguet had organised a screening of Femmes femmes for me: I hadn’t seen any of Vecchiali’s films, I didn’t know him at all, and I found Femmes femmes extraordinary. We met, and he asked me first ‘Why do you want to make cinema?’, and then ‘Why are you an actor?’ ‘To have my name in great big letters on the Champs Elysées!’ ‘You, tomorrow, in my office.’

Pascale Bodet: He liked provocation?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: Exactly. We were in the aftermath of May ‘68, there was constant provocation, humour… He did the same thing with me as Chabrol: after a bit of provocation he dug deeper to see what was behind it. After Femmes femmes we made Change pas de main, which was the first film porno-intello, as they called it at the time, and then we went on to make La Machine.

Pascale Bodet: Pascal, Bonjour la langue was shot in a single day?

Pascal Cervo: Yes.

Pascale Bodet: Were there any rushes, moments of improvisation that were left aside?

Pascal Cervo: My impression was no, I think Paul used everything. Sometimes, when an actor stammered, Paul would say ‘It’s like that in life, you stammer, let’s keep it like that, very good.’

Pascale Bodet: The shrink stammers in La Machine! When Vecchiali shoots a sequence shot, amongst other things it’s in order to give the actor the chance to unfold, to metamorphose. The actor is supposed to have more freedom, and thus to be able to give more freedom to the character, who will unfold and metamorphose along with the actor. Did you like that freedom, or did it frighten you? Did you like acting in those sequence shots?

Françoise Lebrun: I was afraid on En haut des marches, absolutely, because there was no freedom at all. First, there were the rails, a whole impressive installation — you thought to yourself ‘Oh my God, everyone has spent an hour and a half setting this up, I mustn’t mess up!’ Everything was very precise, marked on the floor with chalk: the moment when you had to stop, the moment when you had to say a particular part of the sentence…

En haut des marches (Paul Vecchiali, 1983)

Damien Bertrand: But En haut des marches is the only film where there was no room for freedom, where everything was written, controlled. You started with that peculiar film; maybe the experience was different for Pascal or Jean-Christophe? Jean-Christophe, you said that the famous sequence shot with the psychologist was improvised: I’m stunned, how did you manage reconcile an actor’s improvisation — a two person situation at that — with the camera, which really doesn’t give the appearance of moving by chance? It makes a pendular movement that captures the faces at just the right moment, so that there’s a whole game of anticipation of what’s about to tense up in the faces and the bodies. Did you talk about that at all before starting the take?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: No. It was totally improvised, and I like that, I felt very comfortable. As many actors [comédiens] are taught, one must be aware of the camera and at the same time forget about it, and from that point of view I was in perfect balance. I knew where the camera was, and in the film I see myself in the process of playing with it: turning my face, playing tricks a bit so that it properly captured the face, the side, the profile… All of that was instinctive, it wasn’t too thought out. I think the audience, or the viewer, takes an unconscious pleasure in feeling that the actor is enjoying themselves, even if that enjoyment isn’t conscious.

Pascale Bodet: What you’ve just said — both of you — gives a good idea of what filmic writing is for Vecchiali, doesn’t it? You never get the feeling that in the case of this sequence shot the filmmaker has said to the actor: ‘Speak when the camera is behind the shrink’s back.’ A little tension, a little suspense builds up during that shot, because I have the feeling that, Bouvet:, you’re waiting for just the right moment to speak or to do something or to move. I have the feeling that it’s you who’s giving life to the sequence shot.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: When I start playing with the inkpad, I don’t know if Paul reframed the shot, I can’t remember anymore how he did it, but for my part it was instinctive.

Pascale Bodet: At first, you can’t see that there’s an inkpad there, and then suddenly…

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: …it appears on the screen. That, that was a sort of miracle, a piece of good luck.

Pascale Bodet: And when you say the shrink improvised the scene, what was his score? Had Vecchialli given him any lines?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: …No, we’re in full improvisation. But there isn’t much dialogue, it was more about improvising the gestures.

Pascale Bodet: It was done in just one take?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: Just one.

La Machine (Paul Vecchiali, 1977)

Gaël Teicher: There’s a myth of the single take with Vecchiali. It’s certainly true of Trous de mémoire or La Machine, but not of all the films. I’m thinking for example of the long shots between Edith Scob and him in Retour à Mayerling, where for the sake of the acting there were multiple takes, at the request of one or the other actor.

Pascal Cervo: Yes, sometimes we did multiple takes — twelve on C’est l’amour, for example — but all the same that was rare, and in the end it’s the first that counted.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: When I was his assistant, I was always saying to him ‘But stop, you know very well that the first take was really good!’

Pascal Cervo: On Nuits blanches sur la jetée, we did things in a single take the majority of times, a single take for sequence shots of ten minutes or so with precise text and positions. That created a particular tension. Yet at the same time, I had the impression of being absolutely free inside that sequence, a freedom of breathing and of the emotions. That’s why I love sequence shots: the more I feel myself confined to precise marks and places, the more I exalt. For me, it’s constraint that gives birth to emotion.

Pascale Bodet: When you’re acting in the theater, do you feel the same thing as when you acted in a Vecchiali sequence shot?

Pascal Cervo: Not quite, no. In the theater, I’m less taken up with the technical constraints. And I have less of a feeling that the hors-champ (the offstage [la coulisse]) is in dialogue with the in (the stage itself [la plateau]). That’s what I find to be so great about Once More, for example*.* You’re aware of the actor at work, and not only of the character. There are ellipses inside of certain sequence shots, and I take a real pleasure in watching the actor change state, in seeing the illusion of the character reform before my eyes, in seeing them disappear and come back… That’s also what happens in Nuits blanches sur la jetée. One of the interesting things about the sequence shot is that it records a duration, so even if the performance isn’t right, it’s not so bad, because the shot still records the reality of an actor in the process of acting.

Damien Betrand With Veccchiali, the rules of the game change with each film, but there’s always a dialectic between what is written and what is improvised. Can you give us some concrete examples of the way in which the two terms are worked out while shooting? And how they fit together in practice?

Pascal Cervo: Bonjour la langue is improvised, but I felt in the same state as when Paul gave me a text. I was in front of Vechialli’s camera, and so I was in the state of being directed by Vecchiali.

Pascale Bodet: One often associates the direction of actors with explaining the psychology of characters. Did Vecchiali ever give you psychological indications?

Jean Christophe Bouvet: No. Of course, that’s what some directors do… I’ve experienced that in the theater, because there you have time to work, time to ask yourself questions about your character… To an actress who said ‘But can we talk about the psychology of my character’, Hitchcock replied ‘Think about your cheque tonight.’

Pascale Bodet: The three of us didn’t work with Paul in the same periods. I wonder if there were rehearsals for En haut des marches or La Machine, despite the improvisation we talked about?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: No

Françoise Lebrun: Oh no…

Pascal Cervo: Like in my case, then. No rehearsals.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: No reading either…

Pascal Cervo: We always read the script at least once.

Françoise Lebrun: Together?

Pascal Cervo: All together, yes. Not necessarily the day before filming, it could be well in advance.

Gaël Teicher: Did Vecchiali say anything at that point?

Pascal Cervo: He had this saying: ‘Words are like costumes, if they don’t suit you, you have to change them.’ But in actual fact, I never changed them, any more than I changed my costumes! I would have liked to have changed my costume sometimes… I found myself in costumes that kept me up at night. At the same time, looking back, it’s good, it’s part of something.

Françoise Lebrun: It’s the direction of actors.

Pascal Cervo: Exactly. It’s also the affirmation of an anti-naturalism.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: It’s bad taste. He went too far. I told him: ‘That’s why your films don’t work. They’re masterpieces, beautiful films, but they don’t work commercially because of the costumes and sets. It’s like we’ve gone to Mars, and people can’t relate to it.’

Corps à cœur (Paul Vecchiali, 1979)

Pascal Cervo: In any case, I like that it breaks away from cliché. These types of costumes belong only to Paul. When we wear them, we become like icons.

Gaël Teicher: So it’s the height of bad taste, but at the same time there’s a crazy beauty, right down to the sets and the costumes. The apartment in Corps à cœur is magnificent, Silberg’s jacket is magnificent.

Pascal Cervo: Paul found amazing clothes, he managed to make something of the order of the ‘mythological’. I’m probably exaggerating, but it’s a bit like in Rebel Without a Cause: there’s James Dean’s red jacket, which has entered into the mythology of cinema. Some of Paul’s costumes appear in film after film, and that creates a certain mythology.

Françoise Lebrun: What made me howl with laughter every time were the flower bouquets… There are always elaborate floral arrangements, and you say to yourself, ‘He wants to capture the legacy of Douglas Sirk!’

Pascal Cervo: It’s the colors. You mention Douglas Sirk, and indeed there’s truly a remarkable coloristic aspect.

Françoise Lebrun: He had this great love, Paul, for Demy, and I think they’re a bit like the positive and negative of each other. For example, between Michel Legrand and Roland Vincent, or between Demy’s set decorator, Bernard Evin, who does implausible things that work, and Paul, who always does something a little filthy.

Pascale Bodet: Or a bit synthetic, a bit shabby, a bit emblematic [signalétique].

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: On the music, I don’t agree with you, Françoise.

Françoise Lebrun: Everyone sang Les Parapluies, nobody sang Roland Vincent.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: Because of the films’ lack of success.

Damien Bertrand: All the same, Roland Vincent’s music for L’Étrangleur is hard not to get stuck in your head — it’s haunting. To me, it doesn’t seem to be a question of whether we want to hum it, like the music in Demy’s films, but the fact that it stays in your head. And it allows itself to express dissonances, very dark things, anxious sounds that echo the states of the characters, which we never find in Legrand’s music for Demy. So above all, there’s a kind of fidelity to the subject and the characters in the way Vecchiali uses this music: it has its village dance element, close to the audience, who will happily listen to a show hosted by a Johnny Hallyday doppelganger. For me it would be a kind of aesthetic aberration to use music that is more openly brilliant.

Françoise Lebrun: I’m more moved by Fauré in Corps à cœur.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: Now that’s magnificent. He can allow himself that because he truly measures up to it. Because that film, Corps à cœur, is magnificent.

Françoise Lebrun: There is in Paul a sensibility, an emotion linked to music.

Pascale Boudet I find that Vecchiali often incorporates music in a shrill way. In the bar scene in La Machine, which is a long, mobile sequence shot, melancholy because the characters are all seen from outside through the windows of the café and the camera moves from one window to another, the music comes in and it’s too loud. In Trous de mémoire, it’s the same, the music is too loud and occurs without us expecting it, out of the blue. The music ‘screams’. A kind of music that’s the equivalent of a shot, going against the idea that music accompanies the emotion that arises from the shot. So with shot and music, Vecchiali can achieve the materiality of contradiction. Ears and eyes are in tension to achieve more intensity. It’s a Godardian thing that Vecchiali takes up, and the emotion that results is Accords et désaccords, one of his punning titles.

Gaël Teicher: How was it to perform with him as an actor?

Pascal Cervo: First of all, it’s complicated for me to act with someone who is directing, because I don’t feel watched the way I would like: if the director is both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’, he’s with me, but not completely. I enjoy going on adventures and experimenting, but acting with Paul wasn’t my preference. I couldn’t help but see the split between him acting and him already preparing the next shot — and because of that, acting in an almost automatic way. I didn’t feel like I was entering into a moment with him and sharing it. Except on Bonjour la langue.

Françoise Lebrun: I don’t think Paul was a good actor. When I acted with Paul, I didn’t get the pleasure that you can get when you share something with an actor. For example, if you see that you’re overdoing it, or something like that, you tell yourself that’s not the point, that what matters is helping him achieve what he wants. That’s why Trous de mémoire was different, a kind of friendly ping pong: there was the pleasure of innocence, we were having fun, he surprised me with his prostate cancer that he suddenly invented, and I thought, ‘Great! What am I going to say?’ But afterwards, in À vot’ bon cœur, he starts to signify too much for me as an actress and as a viewer, he overdoes it. I said to myself, ‘It’s okay, this character can do this, this character who has decided to kill the CNC, he can overdo it in the semblance of life that is filmed.’ But I think I could have said, ‘Paul, you’re really overdoing it.’ But it never happened.

Pascale Bodet: ‘Too much’ on what level? Sentimental? Lacrymal? I get the impression that in Trous de mémoire he himself is taking on the role of standard-bearer for what he imagines to be the quintessential Vecchialian actor, that is, the one who makes it possible to explore a wide open range of behaviors, so as to make his partner laugh, to make them cry, to blackmail them or provoke confessions. This desire to be Vecchialian makes him more voluntarist than Vecchialian. It’s no doubt because he wanted to be the one calling the shots.

Françoise Lebrun: Oh absolutely!

Pascale Bodet: And it’s so visible, it’s like a caricature of the Vecchialian actor, which you respond to, Françoise, entirely, through a more psychological character (nuances and interiority) and so less Vecchialian per se. This doesn’t work against the film — on the contrary, it balances it out: I don’t think Vecchiali is a very good actor in this film, but the antagonism between the performances balances it out. Basically, I think Vecchiali made a distinction between female actresses and male actors, suggesting that with the actress, the woman remains present behind the character, which is not the case with the actor. This would have to be considered on a film by film basis. In Trous de mémoire, I don’t see the man behind the character played by Vecchiali, or else I see the filmmaker. But you, Françoise, remain present as a woman independent of the character you play in the film. In the other films, you would have to see which person, man or woman, survives or ‘pre-lives’ [pré-vit] their character.

Damien Bertrand: In this regard, there is something touching about the last twenty years, which is the increasingly significant role he has invented for himself as a husband and father. Regardless of whether or not he acts well in La Terre aux vivants, what comes through emotionally is impressive. And in Bonjour la langue it’s deeply moving. I find this mysterious and very beautiful, to portray oneself so much as a husband and father, and for it to take on such importance in one’s cinema.

Pascal Cervo: Paul had romantic relationships with women, and I always knew he had this fantasy of having a child. He considered Astrid [4] and me a bit like his children, his cinema children. I really like the fact that Paul mixes everything together, and that in the end, ‘all is true’. Whether it’s his ‘real life’ or cinema, everything is on the same level. We were filming in his house, we were part of his family, we ate the same breakfast, that’s not insignificant.

Bonjour la langue (Paul Vecchiali, 2023)

Gaël Teicher: It was the same when he lived in Kremlin-Bicêtre, his house was his set.

Pascal Cervo: Perhaps there’s one thing he passed on to me: art and life, they’re the same. How you live, how you organize your life, is already an art. You film like you breathe. If art can give him a romantic relationship or children, then why not? It’s very moving. But I come back to the question of whether Paul was a good or bad actor. Regarding his final period, I’m not sure the actor’s accuracy interested him very much. He put himself at a distance where what interested him was seeing someone act: well, not well, it didn’t matter — but truthfully. That applies to him as an actor, too. What I really like in Trous de mémoire is that I feel like I’m watching a documentary about a director directing an actress. In fact, Françoise, he doesn’t let you go, he puts your face in the light… ‘We’ll stand here, I’ll put the bench there and we’ll sit down, and now we’re going to talk about this, and this..’ I see him working with you. And I recognize him completely — he’s not a bad actor [acteur], he’s a bad player [joueur]. He says, ‘We’re going to do an improvisation’ and at the same time he directs everything.

Gaël Teicher: Trous de mémoire, Bonjour la langue and even the last part of La Machine are great films about the relationship between a director and an actor: the director puts himself in the film so that he can document the actor. As for the trial in La Machine, Vecchiali gave you a wonderful role, Jean-Christophe, because it’s you who interested him, perhaps more than the death penalty, more than pedophilia. And when he plays the role of the lawyer, it’s not for nothing: it’s not the role of prosecutor, or someone else, it’s the role that puts him in the place where he, as the director, can watch you. You, Jean-Christophe Bouvet, not Pierre Lentier. And what links you three and these three films, something that in fact goes beyond the question of Paul Vecchiali’s accuracy as an actor, that he is accurate there where he is. He’s perhaps not accurate as an actor, but he’s accurate there. That’s what counts. So yes, he is undoubtedly more Vecchialian in Trous de mémoire than any other actor, but the question ‘what does it mean to act with Paul Vecchiali?’ is not just about acting with him — Pascal, you’ve described it a bit — it’s the fact that the actor in front of you, your partner, is also the director of the film. And he must have known perfectly well that this affected you, that it made you act differently, react differently, that there is something there that bears on the most central apparatus of fictional cinema.

Pascal Cervo: Exactly. I would add that I get the impression that, in the case of Trous de mémoire and Bonjour la langue, in these two improvised films, he invites the actor to come and settle scores. As if he wanted to be critical as a man, as a director. And in that sense, I see Bonjour la langue as the culmination of something that I felt had been underway since Les Sept déserteurs. Perhaps this question had concerned him much earlier. At the time, he told me that the idea of imposing something on people in the role of director, the fact of acting like a god and dictating the behavior of the characters, concerned him a lot. I have the sense that, from Les Sept déserteurs on, this question became central — and that it’s the very subject of the film: he watches the characters and kills them one after the other. It’s as though he wanted to rid himself of this wilful, tyrannical attitude in his final films. And it’s perhaps not by chance that he ended with Bonjour la langue, which could not be simpler in terms of point of view: shot/reverse shots and improvisation. No text, a simple découpage, three sequence shots… It’s as though the film could be made without him intervening in any way except as an actor.

Pascale Bodet: Yes, and that’s why I don’t entirely agree with Gaël: in Bonjour la langue there’s no longer a very visible relationship of a director, as in Trous de mémoire, directing his actor. In Bonjour la langue, Vecchiali gives the impression of having put himself in a position to open up to someone as a character.

Pascal Cervo: That’s it, it’s the context: he needed to say something.

Pascale Bodet: And, unlike the role he gave himself in Trous de mémoire, as an actor in Bonjour la langue he doesn’t give the sense of wanting at any cost to provoke reactions from his partner, as a filmmaker disguised as an actor. This is why Trous de mémoire and Bonjour la langue seem to me to be related but different films, with the actors finally on an equal footing in Bonjour la langue (including in their ability to manipulate). In Bonjour la langue, it seems like Vecchiali wants to give the impression of not directing you, Pascal, other than through what he provokes in you as an actor — from one character to another character. This doesn’t erase the ‘happening’ aspect, but it does erase the Pygmalion aspect. Finally, his acting partner comes alive on his own.

Damien Bertrand: When Vecchiali plays the lawyer in La Machine, he’s standing and Jean-Christophe is sitting, because that’s the situation, because it’s death row, because he represents the last thing standing before Lentier collapses onto the guillotine. Whereas in the films where there are ‘family’ relationships between the characters and him, I tend to see him sitting while you’re standing — in fact, I’m thinking of La Terre aux vivants, when you come back from the cremation, Françoise, and you speak to him standing while he’s sitting.

Françoise Lebrun: It must also be said that Paul ultimately had his harem: there was Hélène Surgère, then I came along, then there was Marianne Basler, then Astrid Adverbe… in fact you had to be a certain age to be in his films.

Gaël Teicher: You don’t include Danièle Darrieux or Sonia Savange in this harem?

Françoise Lebrun: I was in Plan-de-la-Tour when Darrieux turned ninety-nine. Paul called her and said, ‘Everything’s going well, just one more step to climb!’ He had this fascination with Darrieux that lasted throughout, from his early childhood, when he was five and a half, to when Darrieux was a hundred years old. And there was this kind of reproduction. I’m thinking of the prison scene in En haut des marches, where we’re actually both there, as if a thread ran through all these women.

Pascal Cervo: We’d have to check, but I think Darrieux is in all his films.

Damien Bertrand: In the form of photos on a wall.

Pascal Cervo: Perhaps not in Trous de mémoire…

Françoise Lebrun: No! But her photo made it all the way to Plan-de-la-Tour.

Pascale Bodet: I’d like to return to the notion of the Vecchialian actor. Does it make sense to speak about that? Does it exist?

Pascal Cervo: I associate the Vecchialian actor with a certain technical mastery, a theatrical aspect of the actor.

Françoise Lebrun: Theatrical in the sense of over-the-top?

Pascal Cervo: No, in the sense of an actor who has a certain technique. The Vecchialian actor seems to me very technical. It’s perhaps linked to the cinema of the thirties. I get the sense that he wanted actors who acted, who sang, who danced. I turn on the camera and ‘Go ahead, act’. You have to have this ability.

Gaël Teicher: It’s the Hollywood actor, then?

Pascal Cervo: He was very Hollywood! His bad taste could be a Hollywood taste, but with all the lights on. His villa, Mayerling: it’s a Hollywood villa, with the old actress who opens the door — it’s Sunset Boulevard. The Vecchialian actor, I’m not sure if they’re really a Hollywood actor. Technique, yes — but not at all ‘Actors Studio’. On the contrary, the actor plays the part as it’s written, no psychology or preliminary emotional state. If you play the part, ‘we’ll get it’. Don’t ask yourself questions. Just go for it.

François Lebrun: It’s also ambivalence, like with Demy. On the one hand, there’s this passion and knowledge of French cinema between 1930 and 1950, and on the other this dream of Hollywood. There’s a relationship between Hollywood and Kremlin-Bicêtre. Silberg and Patrick Raynal [5] could be toned-down versions of Hollywood heroes.

Damien Bertrand: Of Rock Hudson?

Françoise Lebrun: There you go, of Rock Hudson. But on the other hand, there was everyday life. There was a sort of duality between that reality and this desire for the cinematic embodiment of what it was to be a man. On one hand, fragility, and on the other, kilos of flesh,

Pascale Bodet: But men in Vecchiali are not strong characters, they’re wounded, sick men who cry out…

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: They’re rugby players with the hearts of little girls…

Corps à cœur (Paul Vecchiali, 1979)

Pascale Bodet: There are three types of actors and thus of characters in Vecchiali. There are the Vecchialian characters — and for me those are the women, who are players full of panache who have their highs and their lows. I put Darrieux aside because she doesn’t come from Vecchiali, she is part of the mythology of Vecchiali. So I’m speaking about Surgère, Saviange, Basler, Adverbe. Then there are the men, fragile and sick, for whom the amplitude between the highs and the lows is narrower, with actors such as Silberg, Jean-Louis Roland, Pascal Cervo. Finally, there are secondary roles on the model of the French cinema of the 1930s — we could cite for example Delahaye or Denise Farchy. Whichever type is at stake, the question becomes ‘How to make them play?’ And that seems to me to be the same question as: ‘How to make them metamorphose?’ How, for example, can we make these actors pass from vulgarity to a very elevated regime of language, or how can they pass from confession to play or vice-versa or alternatingly within the duration of a single shot? Vecchiali was able to inveigh on his male actors to ‘play Vecchialian’ in the manner of the actresses that I just cited, and who for me are the dream of Vecchiali’s cinema. That is to say that in the space of a single shot, the actor passes in stages through various types of play and demonstrates a freedom (of playing) that may seem capricious but from which springs a lot of life (of character). Jean-Christophe, you do this, for example, in La Machine. In the scene where the murder is reenacted, Lentier is extremely focused, so focused that he seems absent from himself, and he answers the questions factually, but then he ends up screaming like an animal. Do you remember this shot where you go from concentration to yelling?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: I was helped by something quite clever, which was that we were filming in real time on real sets. For the final guillotine scene, I spent the whole night in the cell, and someone came to wake me up. I hadn’t slept much, and I’d never seen a guillotine in my life. There was no rehearsal, just a live sequence shot in a single take. I was barefoot, and it was very cold at five in the morning — the atmosphere was really very heavy. When I saw the guillotine, I was no longer putting on an act [jouais la comédie], I was inside acting [6] in the sense of the Actors Studio.

Pascale Bodet: And in the scene where the murder is reenacted?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: The same. There was a sinister atmosphere in that disused factory… Paul did something perverse that wasn’t part of the plan. I had told him a little about my cruising, how I was going to pick up the suburban riffraff I adored. Now, there was this disused factory where bourgeois came to pick up little thugs, and where I had one day found myself in a pretty worrying situation, when the young thug who I was hooking up with had friends who were there to beat me up. Luckily I got out of there — at the time I was a fast runner. That’s the place we went to check out. Paul wanted to see this factory where that incident took place, exactly where we were in the pit — the incident where I was lured into the pit where those kids almost slit my throat. When we found this place to shoot, it clicked. I understood what he wanted from me, a visceral reaction. He got it.

Gaël Teicher: Here, can we speak about the direction of the actor?

Pascal Cervo: About manipulation.

Gaël Teicher: Direction of the actor, manipulation, let’s say the trap is part of the mise en scène. Were there other moments when you felt trapped by Vecchiali, and when you knew how and why?

Pascal Cervo: Often. Perhaps a little less on Nuits blanches and Bonjour la langue. Otherwise, I always felt trapped, and it took me a long time to realize what he had wanted to do, why he had made me do certain things that I had found impossible at the time. C’est l’amour is the outstanding example. I didn’t like the shoot and I didn’t like the film when it came out because I didn’t understand what Paul wanted. I didn’t understand it emotionally, I didn’t really believe in the text. And the fact that I didn’t understand didn’t especially bother him. But what’s striking is that in C’est l’amour, he got something out of me that I could never have consciously given.

Pascale Bodet: What?

Pascal Cervo: A side that was… Vecchialian. If there’s a film where I’m Vecchialian it’s definitely C’est l’amour. Something in the body, which escapes me, something I don’t know how to do that he got out of me, I don’t know how. He wanted to get this desperate side, a certain savagery, in a way I found very artificial. The way he had me drink from the bottle, for example, I found that false while I was doing it. It made me unhappy, I felt ill at ease, but it served the character’s state. We sense an unease.

Gaël Teicher: Which made you ‘bring out’ something different?

Pascal Cervo: Yes. It’s not a question of correctness of performance, because I don’t think I’m good in the film, but I express something, an emotion, outside of the performance. I come back to what I think he wanted from actors in his final period: not that they play it correctly, but that something real happens, an emotion. A physical attitude, for example, could be enough for him, more than the correctness with which you could deliver the text. In the scene where Astrid rapes me on the beach, [7] it's a sequence shot that lasts quite a long time, you’re discomfited, and it has nothing to do with the correctness with which a character is performed, in the American way — ‘I put myself in the frame of mind’. Just the fact that he asks us to do this slightly incongruous thing in the middle of the beach, that he films it live and it lasts so long, without découpage, that Astrid puts her hand in my underpants and I laugh, even if that can seem a bit clumsy or intentional… It’s all a little shocking. You witness a rape, you’re ill at ease, and it’s this that interests him: not that we’re good at performing the reality of a rape, but that it provokes that unease. And obviously for me as an actor, with my actor’s ego, I don’t enjoy being that bad, but Paul doesn’t care, he got what he wanted. Once again, not the accurate portrayal of a character who is raped, but the unease of the viewer watching.

Damien Bertrand: When I spoke about a conductor, there is something permanent in his films, regardless of apparatuses or periods: we feel the control all the time, the control of dynamics, in the musical sense. Of dynamics of performance, of emotional dynamics. So there’s a gap between how you’ll feel and how he knows he’ll use you in the film. But I get the feeling that where he never lets up, regardless of how much freedom he gives you, is on this point: the moment when he wants the scene to rise or fall in intensity. Looking back, or when you watch the films again, do you feel any surges or decreases in intensity that aren’t the ones you felt when you were performing the scene, at the time of filming?

Pascal Cervo: Yes! But he really had a vision and obviously he didn’t have to explain it to us. And what amazes me is how completely he had mastered the film before shooting. He had everything in his head, a rhythm that he stuck to.

Damien Bertrand: The rhythm of emotion that is translated through prosody, through the camera movements, through very concrete things.

Pascal Cervo: He had a musical mastery. I don’t know, but I imagine it’s like a composer who hears the music: he heard his film, in terms of the rhythm of the shots.

Pascale Bodet: More than dynamics of acting, we know that he sought a heterogeneity of states, of emotions, and he demanded that from actors: to pass from one state to another, to enter states that you yourselves had not anticipated. More than dynamics, it’s a sort of ‘multifacetism’. The idea, I believe, was that what you do as an actor contradicts what you just did as a character.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: Very dialectical!

Pascale Bodet: Yes, and Dialektik is, from 2013 onwards, after Diagonale, the name he gave his production company. Pascal, could you give examples of moments when you felt yourself pushed to do ‘nonsense’?

Pascal Cervo: The television interview in C’est l’amour with Serge Bozon, for me that was truly nonsense!

Pascale Bodet: Why?

Pascal Cervo: Because I felt I was pushing too much, that nothing was coming from an inner need. So the Vecchialian actor, if we have to define it, is perhaps this: it doesn’t matter whether it comes from an inner need. You have to do the thing, period — it’s what I meant by ‘he has to act, sing, dance’, and the question shouldn’t be about going back to the source. You have to do it.

Pascale Bodet: Jean-Christophe, you started with Vecchiali — although there had been Scandelari beforehand. [8] For years you were the Vecchialian actor — why is it that he didn’t call on you as much after C’est la vie? Why didn’t you do any more acting in Vecchiali’s films?

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: He thanked us all with a television film where we made a lot of money, En cas de bonheur. Then it was finished. I was also departing for other adventures, Biette, La Cité de la peur, commercial cinema which got hold of me, the Taxi films, and now Emily in Paris, all of that distanced me from Vecchiali. And also I understood his films less and less — I didn’t like some of his final films.

Gaël Teicher: Among all the filmmakers of that generation, let’s say the Nouvelle Vague and those around it, there are only two who have founded a school — that is to say, Godard didn’t found a school, Chabrol didn’t found a school, Rohmer didn’t found a school, etc. — it’s Pialat and Vecchiali. Pascale Bodet, Laurent Achard, Serge Bozon, etc., there are many who come from there, who are from that school. And that resonates with what we mentioned earlier, the troupe, the family, the children… What is it about Vecchiali that sets an example, what makes Vecchiali a filmmaker who has sown seeds that continue to blossom?

Pascal Cervo: Now is the moment for the example to be set, more than ever — his way of making films and his spirit are exactly what we need, given the current climate and the difficulty of making films financed in other ways. It’s still an economy, Vecchiali. But what sets an example and what is necessary, at a time when there is less and less room in French cinema, is that intention to make films that start from a reality and construct a fiction on the basis of the real, embracing fiction and anti-naturalism. I once asked Paul the question, ‘Do you expect your viewers to identify with your characters?’ ‘No, not at all.’ There’s no longer much room for films that don’t expect the viewer’s identification. Paul wanted people to be moved by his films, but not by way of identifying with the characters.

Damien Bertrand: Because he shifted the center of gravity of the spectacle, like most good filmmakers. What constitutes the spectacle in their films is the writing, the mise en scène, the relationship with the world.

Jean-Christophe Bouvet: He also played on fragility, on febrility, to counter virtuosity — there’s nothing worse than virtuosity, you need wrong notes. Callas, filled with emotion, hit a wrong note and it was magnificent.

Damien Bertrand: Vecchiali created a manifesto of the sketch, the line must be quick.

Pascal Cervo: It’s the movement, it’s the breath that counts — because when you stop, you die.

Rosa la rose, fille publique (Paul Vecchiali, 1986)

Pascale Bodet: But Jean-Christophe, I don’t agree with you about the last part of his oeuvre. You have to watch and try to understand his final films in the light of his early ones, because if he continued it was because he had something more to do. With the last part of his oeuvre (I pass directly from Bareback to Nuits blanches sur la jétée), I find that Vecchiali finally accessed — a direct access — the flow of love that he was searching for from the start. A flow of love, that is to say that passion is the sole driving force of the characters, whereas the quotidian is the condition of filming for the actors, actors launched into experimentation. In his final films, there is a democracy of casting, and the actors are often not the age of the characters. Hollywood is combined with the sincerity of a point to be made: about love, life, death. Everyone is actually old, but inhabited by youthful affects, for example. It’s here that Vecchiali ends up becoming much more experimental that he was at the start, with a relationship to his shooting conditions that is much more quotidian, prosaic, poor, discordant (Godardian?) and less and less Hollywood, illusionistic, phantasmatic — what inspires dreams. And so more and more stripped to the bone, implausible, unprecedented, towards that flow of love: his final films ultimately crown those for which he is best known, because with age he managed to grow much more in tune with life itself. His final film, Bonjour la langue, is the summa of this relationship between art and life.

Interview conducted in Paris, 9th February 2023,

From Paul Vecchiali: Once more, Les éditions de l’oeil, 2023, pp. 101–128

Notes

For Paul Vecchiali, Jean-Christophe Bouvet appeared in, amongst others, Change pas de main (1975), La Machine (1977), C’est la vie ! (1980), Masculin singuliers (1983), Le Jurés de l’ombre (Lebrun En cas de bonheur (1989), Victor Schœlcher, l’abolition (1998), À vot’ bon cœur (2004); Pascal Cervo in Faux Accords (2014), Nuits blanches sur la jetée (2014), La Cérémonie (2014), C’est l’amour (2015), Le Cancre (2016), Les Sept Déserteurs ou la Guerre en vrac (2018), Train de vies out les Voyages d’Angélique (2018), Bonjour la langue (2022); Françoise Lebrun in En haut des marches (1983), Trous de mémoire (1985), Fugue en sol mineur (1992), La Terre aux vivants (1994), À vot’ bon cœur (2004), Et plus si aff (2006), …Bouvetemble d’être heureux (2007), Le Cancre (2016).

Translator’s note: Liza Strouvé, wife of Georges Strouvé, director of photography on more than a dozen productions by Diagonale or Vecchiali.

Translator’s note: Centre Nationale de Cinéma.

Astrid Adverbe, actress in several of Paul Vecchiali’s films, and with Pascal Cervo in Nuits blanches sur la jétée, C’est l’amour, La Cérémonie…

Actor in Once More, Le Café des Jules and À vot’ bon cœur.

Translator’s note: in English in the original.

In C’est l’amour.

Jacques Scandelari directed La Philosophie dans le boudoir in 1971: it was Jean-Christophe Bouvet’s first cinema role, before Change pas de main.