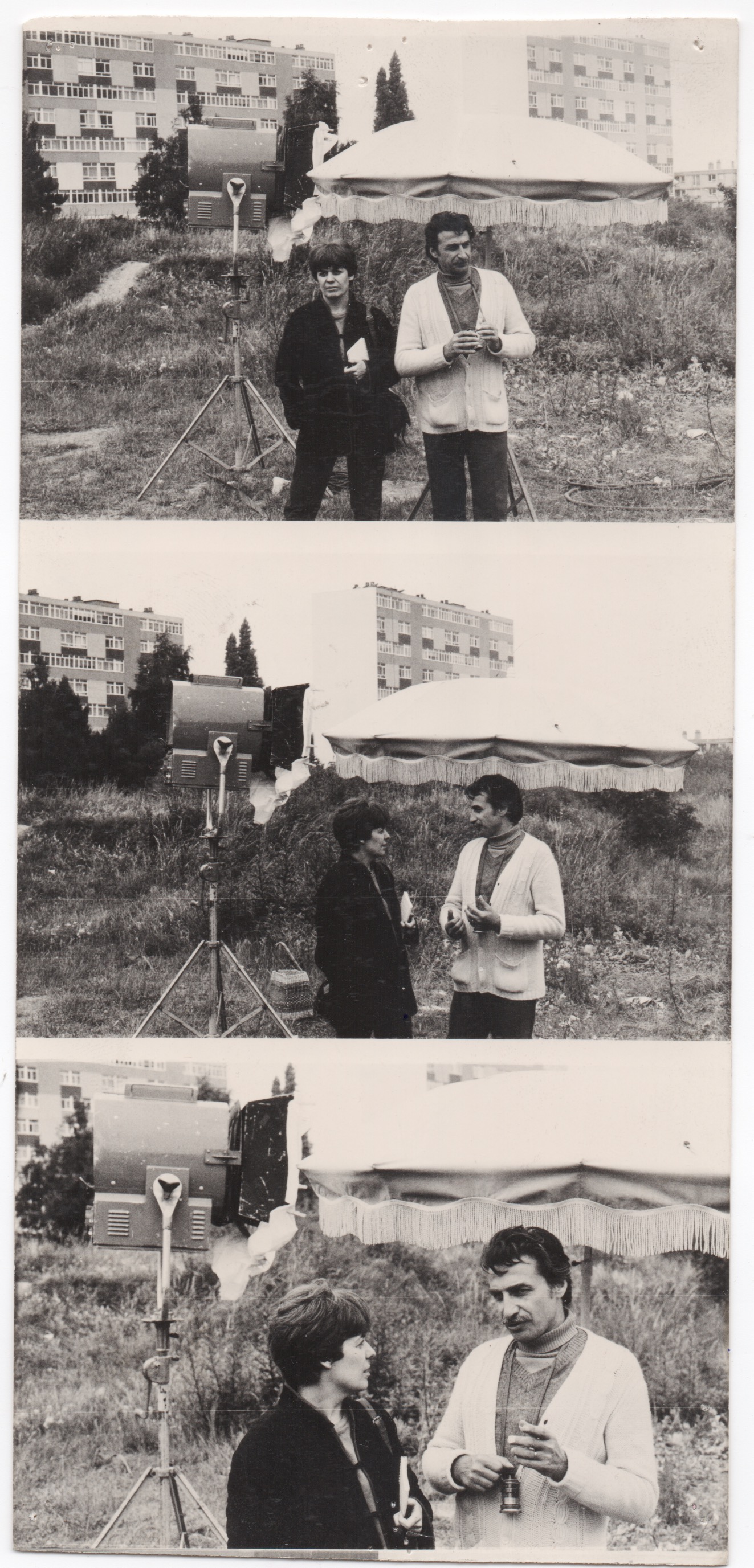

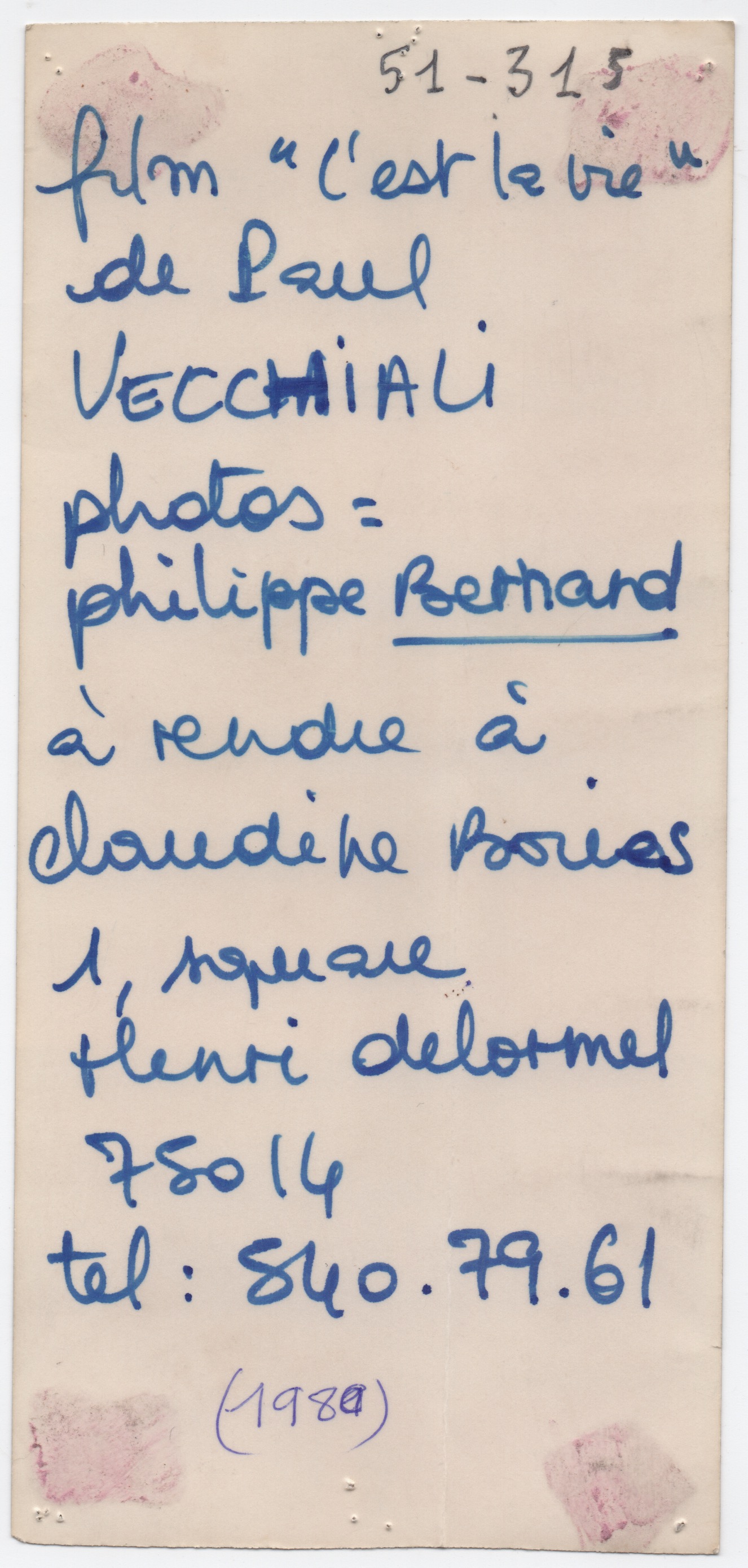

Is this photo from the set of La Fille du magicien?

No, not at all. It was from my first meeting with Paul, during the shooting of C’est la vie ! in 1980. At the time, I was writing articles for Révolution, which was financed by the PCF without being part of L’Humanité. As it was a cultural newspaper, it had a certain independence. And so I had done a report on the shooting of C’est la vie !, and it was there that we met. I had seen Paul’s films since L’Étrangleur.

And how did you come across L’Étrangleur, was everyone seeing it at the time?

Oh, no! I went to see everything strange at the cinema. That is to say Paul was a UFO.

You had done theatre...

I did theatre with Jean Vilar, with Bernard Sobel, with Gabriel Garran and with Armand Gatti. As an actress. I did theatre, I eventually earned my living through acting, but I was crazy about cinema. I’ve always adored it. The first film I saw was in primary school, Le Paradis des pilotes perdus. I had cried. Cried, cried.

Did you go to the Cinémathèque on rue d’Ulm in the late fifties and the early sixties?

I started going to rue d’Ulm with Guy Chalon. I was nineteen years old, it was in 1962, the landmark date for me was Charonne, [1] the demonstrations against the Algerian war. Guy had founded an associative film club called ‘L’Action du spectacle’, with very young and very politically involved filmmakers who showed Riz amer as well as B movies, Mario Bava… Guy had made some militant films about the Algerian war.

Did you hang out with the militant camp rather than those critics like Moullet or Vecchiali?

Absolutely. I was very political, because I did theatre in the banlieue, because I came from where I came from, because I was very faithful to my cultural roots.

At the time, Vecchiali also went to rue d’Ulm.

But that’s not where I met him. In any case, the Vecchiali I knew is not the Vecchiali others know. That is, I didn’t know the Vecchiali with a bunch of film buffs and all that. I knew the Vecchiali who lived in Kremlin-Bicêtre in the alley, with Pierre, his boyfriend who was a caterer for Diagonale. When you arrived at Diagonale, there is Paul’s office on the left, and several rooms at the back which were the kitchen, and it was Pierre who cooked. For me, that was Diagonale. Paul was someone who was extremely close to the working-class world.

Between this first meeting in 1980 and your arrival at Diagonale, how did things go?

I was shooting Juliette du côté des hommes (1981). I invited Paul to the preview screening, knowing full well that heterosexuality pushed to such an extent wasn’t really his cup of tea: for a woman to say how much she finds men wonderful, for her to go and see to understand what’s going on in their heads, and for it to end with a guy saying ‘What we’re looking for is the tenderness of the woman’. Well, not at all: he really liked it, he left saying, ‘Listen, my dear, hats off to you! For a first film, it was good!’ I was pleased.

It’s your second, isn’t it?

But he hadn’t seen Femmes d’Aubervilliers (1980) then. Afterwards, I had the help of the CNC to make Lointains boxeurs, which he asked me to produce, as he was aware of everything and was producing quite a few short films at the time, including his own… In short, at one point I went to Diagonale, and he said, ‘Here’s Claudine, my friend’. He edited Lointains boxeurs. We got on very well, and then I made Portrait imaginaire de Gabriel Bories, and I was the one who asked him to edit it. It was an INA and television production. All the work on the archives and the music greatly interested him, and he knew that whole era of French cinema like the back of his hand. We got on very, very well. I came from a working-class background, and, between Paul and I, it was love at first sight, there was a lot of brotherhood between us. I was as much of an outsider as he was in many ways. Obviously, there was the matter of homosexuality. I wasn’t homosexual, but I was in theatre, a milieu in which there were many homosexuals. And then I was in a committed relationship to the world with which he was completely in phase. Though he was on the right and I was far left. Paul hated socialists above all. Oh, the socialists, he couldn’t stand them, he preferred communists to socialists. But in fact, he was fundamentally an anarchist. Me too. There was the ‘we don’t find ourselves anywhere, we’re rebellious and we understand each other’ side of us, and we make films, we like that, and that’s it.

Did you, who were politicized and who had worked for fifteen years at the Théâtre de la Commune d’Aubervilliers, find that there was a political dimension to the way Diagonale functioned?

I found it completely revolutionary, yes! Paul did without the industry completely! He never, ever made the slightest concession to the film industry! That, for me, is what is revolutionary. For me, being revolutionary is not in the sense of the political spectrum. It is in the sense of a profound positioning, which was ‘They won’t get me, they won’t get me, I won’t give in’, and that was his whole life.

Who are those who ‘won’t get us’?

The idiots. The bourgeois. We detested them. Those who want to get us. Those who make crappy films. Those who have no hope. Those who indulge in their constant complaining. The administration. Well, we can make a list. So, naturally, after Lointains boxeurs and Portrait imaginaire de Gabriel Bories, I suggested he read La Fille du magicien, he thought it was great. And that’s when you discovered Paul the producer. Paul the producer is rather special. That is, he tells you, ‘We’re going to make the film, no problem. In any case, we’re going to make it. So you send it to the committee, [2] in your name, because if it’s me, you won’t get it, so in your name.’

Did he consider himself a persona non grata?

Yes. So I got the advance. He said, ‘Here we go!’ And I said, ‘But there’s not enough money!’ He said, ‘Listen, that’s your problem. I think there’s enough. We’ll do it like this. But if you want to find some,’ — we had signed a contract — ‘do what you want’. There you go! So, for a year, I looked for money. First from a producer, a Lebanese who knew I was with Vecchiali, but, first mistake, he began by saying to me: ‘Ah, your script is great, but I’d still like to revise certain things. So I’ll pay a screenwriter who’s going to work with you.’ Then I got on very well with the screenwriter, who was a very nice guy, but to everything he brought me in terms of the script, I said, ‘No, no, no, no’. After that, Danièle Delorme and Yves Robert offered to take the film. They said they loved the script, but I didn’t follow up because Danièle Delorme told me, ‘You will come every weekend to our country house, and we will work together’, and I did not like that. I saw myself taken by hand, mothered by these two ‘personalities’ in their beautiful country house, and I didn’t go. Anyhow, after a year, I came back to see Paul, I told him, ‘I haven’t found it’, he told me, ‘That doesn’t surprise me, so let’s do it!’

What did you expect from a producer?

Money!

You thought he was going to get some for you.

Of course!

Was there enough in the end?

Obviously! (laughs) By not being paid, but that was the deal. Paul was not paid either. The entry code to Diagonale was to make the film with the money he had without going over. It was a very serious commitment. For La Fille du magicien, it was shot in four weeks, that was it and that is it.

Vecchiali is credited as screenwriter.

Oh yeah? He came up with that…

It’s true that, at Diagonale, he did one thing or another and didn’t necessarily credit himself with the position in which he had actually worked.

Perhaps he gave himself some author’s rights like that, I don’t know.

So he didn’t work on the script?

We had discussed the script a lot, but no, he didn’t write it. I believe he liked the side of it that was slightly nonsense, well, somewhat light. But I think that, ultimately, he didn’t find the film light enough. When the film was finished, he told me something significant, ‘It’s a very beautiful film,’ — he told me, perhaps sparing my sensitivity, I don’t know — ‘it’s a very beautiful film. It could have been a great film, but it’s like a river with a pool of oil in it, so it’s not a river’.

A pool of oil on the surface or under the surface?

It doesn’t matter, it stops the flow, the surge of joy, the transparency of the waters. It weighs down, and so it doesn’t flow as it should. On the level of the unconscious, he was absolutely right, because that was exactly where I was on a personal level. I came out of it with Monsieur contre Madame very specifically, because with Monsieur contre Madame, I succeeded in talking about suffering, whereas I couldn’t bear to talk about it before. I thus wanted to do light, cheerful things, even if I wasn’t cheerful. I think he was right, what was wrong with La Fille du magicien was that there was a fundamental lie which was not right, which was not true, which was this so-called lightness. In reality, it would have been much better if I had been able to say something tragic at the same time.

The character is presented as a victim of abuse, and her father as the abuser.

Yes, and it’s not addressed at all. I thus think there’s something wrong with love in the movie. Today I can allow myself to say, in retrospect, what I now see. The only loving characters in the film are the father and the mother, and I wanted these two actors who play these roles.

Hélène Surgère plays the mother…

And Jean-Paul Roussillon the father. He’s great. He came from theatre. They all came from theatre, that was my idea.

Surgère who plays the mother and Patrick Raynal who plays the aviator, for me, come from Vecchiali’s cinema!

But they did theatre, too. Patrick did a lot of theatre.

You wanted these two actors, or was it Paul who suggested them to you?

It was Paul who suggested Patrick. I wanted Hélène. For Patrick, I had wanted something else entirely, a much more cruel man, that was also a mistake. Patrick is a lovely, handsome guy. Paul told me, ‘Take him, you won’t have any problems’. But there’s a small problem with the casting, because Anouk Grinberg and Patrick Raynal didn’t work together, so it didn’t help to create the love between their characters.

Vecchiali is known for his extremely rigorous setups with floor markings, but he didn’t rehearse lines. There were readings beforehand, before shooting, but all the emotion had to arise once he said ‘Action’ and the camera rolled. Did you direct in the same way?

No, and it exasperated this asshole production manager Paul had hired and later fired. This guy said, ‘When you come on a shoot, if you are the director, you know exactly what you want. First you set up the camera, then the actors’. I did the opposite. I set up the actors, we rehearsed, and then I did the découpage and we shot. It was more of a Renoir method. We didn’t rehearse lines, no. But I did not do things like Paul at all. I set up the actors first. I didn’t have any problems with actors and actresses.

What does that mean?

But I think there are people who have enormous problems with directing actors! Either it gets too aggressive, or too codependent. I directed actors, but with a lot of empathy, a lot of sympathy. I loved them, whoever they were.

It was your choice of method, Paul respected it, but did he not give you feedback in the editing room?

Paul was a tyrant, but he was a good tyrant. It was Fassbinder’s mother who said that in a small film he made about her: for Germany to work out fine, she says… ‘A Führer? Nein, nein, a tyrant, but a good tyrant!’ [3] (laughs) But I don’t deny the atmosphere of the film, what it refers to, the colors, the bad taste side of it.

There’s a side of the film that’s really ‘out there’.

Yes, but I really like that, I wanted this ‘out there’ side, so I can’t deny this today. Paul also liked this side, both in the script and in the project. But at the same time he wanted the ‘in there’, the ground, that is, he wanted what we talked about: the heavy, solid side, so that it is life, life as the reality that’s there, and that is what isn’t in the movie. The script was extremely lovely, Paul had liked it a lot. In fact, he was probably imagining another film.

Imagining that you were going against the script?

Perhaps something like that, he didn’t say it to me in those words.

The film is very strongly anchored in the thirties. The plane seems to have come straight out of Grémillon’s time. Is that the case?

No! It’s a plane like many that were found on airfields, which were flown for maiden flights. But whether it’s a plane or a caravan, these are things that come from far away in the imagination, from World War I or the Zone — I spent my entire childhood on Davout boulevard, one of the Maréchaux; [4] there was no ring road at the time, so as soon as you crossed the boulevard, you were in the Zone, a world with gypsies, with trailers, with demolished things, with bad boys or bad girls like I. (laughs) So there’s the world of the Zone, and then these planes that probably come from my father’s story, without me being aware of it at the time. All that is very nostalgic, but something of tragedy and nostalgia isn’t acknowledged. For Paul, that was the problem with the film, when he told me it was as though there had been a pool of oil in the river. The oil and the water should have mixed.

For Vecchiali, to make a film is to take risks.

Yes.

From an aesthetic point of view.

Yes.

Do you have an example?

For example, the editing of La Fille du magicien. The shot where the pilot and the girl meet at the beginning. The shot was wide, and I didn’t know why, I was doing it wrong, I reframed the shot into a close-up on Anouk Grinberg. And Paul got up from the editing table, went to sit on the couch, and said, ‘I’m quitting’. And I said to him, ‘But what?’ And he said to me, ‘You had a magnificent shot. You had a light that was transforming. And you cut this shot to give me a crappy one?’ (laughs)

And you agreed?

Of course, he was completely right. It was a mistake. It was clumsy.

It would have been riskier to go with the wide shot.

Of course. It would have lasted, obviously. And I was taking this risk with the shot length. That maybe nothing would happen. There was that. There was also his reaction to the script girl, Dominique Faysse, and it was funny. He thought there were faux-raccords, things that were not good in terms of script supervision. So he said to the script girl: ‘But why did you let that happen?’ ‘Well, because Claudine always told me that realism doesn’t matter.’ So he said, ‘But it’s not about realism! When she tells you that, you know what you should do? You get down on the floor and say “I refuse”. And Dominique said, ‘Next time, I’ll do that. I’ll get down on the floor and say “I refuse”’.

He was attached to a form of grammar.

Absolutely. That is, it had to be very well done. It wasn’t about doing whatever. It was about sticking to a shot because there was a reason to stick to it, it could be a reason related to the script, to the lighting, to the acting, to the actors at that moment, but, at the same time, there being faux-raccords was out of the question. The editing must be good. Paul was an exceptional editor. He knew exactly where to cut, and the first cut was the right one.

You mean that he related to the shot as a living organism, and that he knew when to cut the umbilical cord?

Yes, that’s it. Every time there was something he didn’t like in a shot, he got sick. Really sick! He went hysterical, or he went to bed.

Did it make him sick even when they weren’t his films?

Absolutely. Paul had a hysterical relationship with the material.

When editing other people’s films, was Paul making his own films, or was he really putting himself at the service of other projects?

He couldn’t help having ideas for direction, let’s not exaggerate! But for La Fille du magicien, it was very cut up, there weren’t many takes, we didn’t have a huge selection to choose from.

What did you learn from Paul?

Integrity. Not psychological integrity, but integrity in work and in one’s relationship to cinema, that is to say, ‘We’re not here to please, we’re not here to say what we think about this or that, we’re here to make a film’. In my life, I have met very few filmmakers with as much integrity as Paul had with cinema. He had a relationship of total purity with cinema. What counts is the film, period. It’s not me, it’s not the actor, it’s the film. And that, for me, is lesson number one with Paul. If you’re going off the rails, that’s not important so long as there’s still the film.

Your militant side didn’t bother him?

He didn’t give a damn. Paul told me, for example, that if there hadn’t been paid leave, we would still be able to film on deserted beaches. Likewise, when they built the Louvre Pyramid, he was furious, ‘We will not be able to shoot a historical film in the courtyard of the Louvre anymore.’ He brought everything, everything back to cinema. I think the rest meant quite little to him. What overwhelms me in Paul’s films is cinema. How he does it, the image, the editing, the staging of the actor’s presence, ultimately, the mise en scène.

He said, ‘I cry for cinema, I don’t cry for characters and situations’.

I felt cinematic emotions. What I liked was that he kept a distance. That distance was wonderful to me. I would say he was ‘lean’, in that there was something about him that was… not cruel, but chop chop chop chop. He doesn’t add flourishes, he doesn’t try to seduce you, he doesn’t try to get you. He does one thing and he does it with integrity. There is incredible integrity in this filmmaker. It was the same in life, by the way. He was someone of very great integrity, all while being a pervert, a real pervert, but he knew that. Mental perversion is a form of thought. I’m not talking about sexual perversion. Pascal Cervo says it very well: he goes about it in such a way that you cannot say no. He traps you, yes, but he traps you with love. You don’t feel like you’re being turned into a sadist, he’s not a bad sort. He’s ‘perverse’ in the sense that he knows exactly where things are going, he knows what he wants to achieve, and he goes in order to get there, he goes no matter what.

Is it his right-wing side?

Yes, his right-wing side on one hand and his righteous side on the other. He’s double, but who isn’t? I like this feature of his films a lot.

After La Fille du magicien, you no longer collaborate.

It must be said that Paul was very mad at me for no longer making fiction films. He thought I should do it again, that I was very gifted at it, that I was a very good director of actors. And he didn’t understand why I only made documentaries. He said it several times, including when we went to Belfort for a retrospective in 2006, where he presented La Fille du magicien.

What did you think?

I think La Fille du magicien was traumatic for me, because it didn’t work commercially and it took me years to recover. I think I discovered something else with feature-length documentary cinema. What I discovered with direct cinema fulfilled me. I renounced fiction, but I still had two loves, theatre and real life. And real life was like documentary cinema, so there you go. But I think I was crushed by the failure of La Fille du magicien. And that’s the reason why, afterwards, I didn’t do anything Paul told me to do to keep the film, the copies, the rights… Today I’ve lost it. But it doesn’t matter. For me, things are different today; at my age, I focus on: now!

Was Paul interested in documentary cinema?

He wasn’t interested. The only documentary he accepted as a documentary was the documentary I hate, that is, the documented documentary. For example, we take a writer we like, and we’re going to narrate his life, read his texts, make him known…

Wasn’t he responsive to the search for a form in documentary cinema?

For Paul, it was all about fiction. He wasn’t going to get lost discovering what documentary cinema that tried to move away from the ‘docu-cu’ [5] was like. He didn’t have the time, he had to make his films, and his films were fiction films, that’s all.

Yet he edited two of your documentaries, Lointains boxeurs and Portrait imaginaire de Gabriel Bories, and you can’t say they were ‘docu-cu’.

That’s true. And he adored Portrait imaginaire.

Editorial note: Claudine Bories has graciously shared with us two links to view the documentaries of hers that were edited by Paul Vecchiali, prior to the filming of La Fille du magicien.

Lointains boxeurs (1982): https://tinyurl.com/boxeu

Portrait imaginaire de Gabriel Bories (1984): https://tinyurl.com/pimgb

Remarks gathered by Pascale Bodet (extracts) in

September 2025. Thanks to Emmanuel Levaufre

Notes

Translator’s note: referring to the Charonne metro station massacre on February 8, 1962.

Translator’s note: commission de l’avance sur recettes.

Translator’s note: inexact quotation of the last line spoken in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s segment for Deutschland im Herbst (1978): ‘The best thing would be a kind of authoritarian ruler who is benevolent, kind and orderly.’

Translator’s note: referring to the boulevards encircling Paris, most of which bear the names of marshals who served under Napoleon I; more specifically, it may also indicate La Petite Ceinture, a railway that runs within these boulevards.

Translator’s note: cucu, sometimes written as cul-cul or cucul, describes that which is ridiculously gullible, cutesy or corny.