Discovering the yellow Cahiers

Serge Toubiana: When did you first come across Cahiers du cinéma?

Jean-Claude Biette: In 1958, when I was in high school. One day, a friend showed me a magazine with a still image from Louis Malle’s Les Amants — a scandalous film at the time — printed on its yellow cover. I found the magazine, with its typography, images and layout, very beautiful. I discovered this field I hadn’t known about, and it attracted me. Like all kids, I went to the cinema. Everyone did back then, that goes without saying, but watching films didn’t entail thinking that cinema was of cultural interest. Far from it.

Reading Cahiers, I realized there were hierarchies: some films were viewed favorably and others not. Suddenly, this awoke an interest in me. In literature and music, there were figures I really didn’t like and others that were very dear to me. I was used to making choices in music and literature, wholly subjective ones, since, at that age, preferences were shaped by subjectivity rather than reasoned choices. Reading Cahiers exposed me to a system of values, and when you’re an adolescent, you’re searching for a system.

S. Toubiana: Were the films you were watching at that time those that were being discussed in Cahiers?

J-C. Biette: At that time there was only one type of cinema, with the occasional so-called ‘artistic’ films. For me, artistic cinema was limited to Cocteau, a certain French cinema… During three summer stays in England, between 1956 and 1957, just for the fun of being a viewer, I discovered the films of Hitchcock, especially The Man Who Knew Too Much, and also films like The Searchers and Land of Pharaohs. I was very impressed by them.

I watched all kinds of films and, later, when I noticed that Cahiers and I disliked the same films, I was pleased. I started reading the magazine around the time they published the infamous ‘Brussels referendum’, in ’58, which crowned the ten best films in the history of cinema. Cahiers proposed its counter-list, and I tried, in vain, to understand why the magazine pitted Der letzte Mann against Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, or why they favored Mr. Arkadin over Citizen Kane. What fascinated me about these lists was the westerns that landed in the 24th position, for example. I had one desire: to watch these films, so I started going to ciné-clubs and the Cinémathèque…

S. Toubiana: Did you have a marked preference for American cinema over European films?

J-C. Biette: Yes, but the demarcation was unconscious. I went to see Bergman’s films, which came out regularly, Eisenstein’s films, all of Hitchcock’s films. I remember that in the summer of the year of my baccalaureate, Der Tiger von Eschnapur and Das inidische Grabmal played at the Gaumont-Palace. I found the posters beautiful, but for me Fritz Lang was the man who had made M: Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder, a serious film, and I was a little suspicious of Der Tiger von Eschnapur. In September 1959, Cahiers put out a special issue on Fritz Lang; I had spent that whole summer in a boîte à bac [a cram school, often a private one], and I had to repeat the baccalaureate in September, near Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The weather was nice. I read the entire Fritz Lang issue at the Café de Flore before taking a Latin test in the afternoon. Reading the issue was so exciting that I failed my Latin test and my baccalaureate again. Because of Fritz Lang!

I then found out I wasn’t alone in my corner reading Cahiers, and met Dennis Berry, Jacques Bontemps, Barbet Schroeder, and Jean-Louis Comolli at film theatres… Later, I met Eustache and you, Jean. It was around 1959–1960…

Der Tiger von Eschnapur (Fritz Lang, 1959)

L’Avventura or Hiroshima mon amour?

S. Toubiana: The screening of Antonioni's L’Avventura was one of the major events of Cannes 1960. Do you think it is the film that strongly marked the rupture between classic cinema and modern cinema?

Jean Narboni: For me, modern cinema, as an institution, goes back to Citizen Kane: this is what Jean-Claude calls ‘artistic cinema’. This was an established matter, if we wished modern cinema to have become classic. For me, the film that pulsated with the question ‘What is modern cinema?’, in 1959, was Hiroshima mon amour, more so than L’Avventura.

J-C. Biette: That’s exactly it. For me, modernity was Bergman’s Nära livet, a film that spoke about modern things. Then, Hiroshima mon amour was a shock, even for someone like me, who loved American films above all else. I absolutely did not reject Resnais’s film or, later on, Antonioni’s*.* I liked them less than the latest Lang or Hawks films, but I liked them all the same. On the other hand, I instinctively rejected films that aped modernity, and these films were already intimidating the critics.

J. Narboni: The irruption of modernity with the release of Hiroshima prompted a large roundtable at Cahiers, with Rivette, Rohmer, and others. It was not self-evident, but people felt they had to discuss it. There was a division between what was called the ‘right bank’ and the ‘left bank’, an undoubtedly political opposition. Resnais, Marker and Varda were on the ‘left bank’, and a rather ‘right bank’ magazine was forced to take into consideration a film it could not reject in the name of aped modernity. If opinions about Hiroshima mon amour were very nuanced, it was because you could feel that something new was happening. This phenomenon went beyond the cinephile circle. Suddenly, people thought to themselves that a story of this kind had never been told: Japan, the atomic bomb, the aesthetic ideas that came up in conversations at the time; the narrative, the musical rhythm, the rejection of chronology…

J-C. Biette: Even people who weren’t particularly demanding when it came to films treated Hiroshima mon amour with respect, because it was a major sensation.

As I was saying, I discovered the magazine through the issue they put out with an image from Malle’s Les Amants. What really struck me about the film was the sex scenes. Personally, I found the sex scenes in Hiroshima mon amour much more beautiful and not without a connection to those of Malle’s film, which came out two years prior. It was as though there was a progression between the films, a deepening of the same emotive material: on one side, prose (Les Amants), on the other, poetry (Hiroshima). Resnais’s film inscribes itself in memory forever, just like Nuit et brouillard, which today seems to me to be one of the beacons illuminating the totality of cinema.

J. Narboni: One can say that the ‘right bank’ equivalent of Resnais’s film was À bout de souffle.

J.-C. Biette: I remember that I didn’t really feel like seeing it. Around that time, light became a determining factor for me. I was very impressed by the beautiful light in Hiroshima mon amour. I didn’t like the light in Les Amants or even Les 400 coups: it was the factor that made me say yes or no to the films I discovered. The shock of seeing L’Avventura came first and foremost from its light. The same goes for Le Petit Soldat, the first Godard I saw, at a screening at the Sorbonne, during which Godard was heartily heckled by communist students.

J. Narboni: One can say that Rossellini is the great inventor of modern lighting. The films you cited, À bout de souffle, Les 400 coups, and, to a lesser degree, Hiroshima, were Rossellini’s heirs. Hence the question: what bothered you more about Les 400 coups and less about À bout de souffle?

J.-C. Biette: Discovering cinema was a very anarchic process for me. I didn’t know Rossellini’s films at that time. I had only read about them in Cahiers…

J. Narboni: What was highlighted in Neorealism was less the light and more the actors filmed in the streets, the social dimension, the vision of the war, the rubble, the wandering youth…

J.-C. Biette: Just because we admired Rossellini or tried to follow his example doesn’t mean that the element of light would become the natural legacy for films inspired by him. I discovered later that the light in Rossellini’s films also comes from Italy, from locations. The light in Paris had nothing to do with that. Only Rossellini succeeded, in his final film about Beaubourg, in making the light in Paris resemble that of Rome: in the first shots on the roofs, with the sound of bells, on the day he filmed them there was a ‘Roman’ light.

What made me really want to see certain films during that period were the stills published in Cahiers: seeing them was more than enough to make me dream. Looking at a still I imagined a whole set of things, an entire world of emotions, hidden but strongly evoked by these images. Watching the film, you could find the same strong impression imparted by the still images derived from it.

For me, Cahiers was the magazine that claimed: this policier or that adventure film were as much great cinema as… What I absolutely dreaded was watching Les Visiteurs du soir at the high school ciné-club. It was a reference point for official art, the professors’ cinema. I always came out of it feeling profoundly ill at ease. Eustache has rendered this sentiment very well when he had Léaud say, in La Maman et la putain, in reference to Jules Berry: ‘This heart that beats, this heart that beats.’ I really hated that junk. I never wanted to see that film again. A minor western by Fritz Lang gave me a sense of freedom and emotion that wasn’t dictated by the adults who, honestly, bored us stiff. Right-minded people mocked and disapproved of these policiers, westerns and adventure films that Cahiers defended.

I had a rather right-wing friend in high school who defended Clouzot by opposing him to Hitchcock; he sang to me his praise of Les Diaboliques. He also brought up Bresson, undoubtedly because Bresson was a French filmmaker, and because the cinematographic austerity in the films he had made at the time, Un condamné à mort s’est échappé and Journal d’un curé de campagne, was serious and terribly moralistic.

Balzac–Helder–Scala–Vivienne

Before I read Cahiers, I had discovered cinema via Cinémonde: a weekly magazine that had an insert that included the programs playing at all the theatres in Paris. There were the circuits on the Champs-Elysées and those on the Boulevards, and the very names of these theatres were very evocative: ‘Rex–Normandie–Moulin Rouge’, ‘Balzac–Helder–Scala–Vivienne’, ‘Barbizon–Saint-Antoine–La Cigale’,… When a film showed in several theatres, one knew they were genre films or adventure films — an almost agreed-upon sign of aesthetic inferiority.

Ciné-clubs were important spaces for discovering films. Studio Parnasse, for instance, had its Tuesday nights. At the entrance, you could write down the titles of films you wished to see on a register. Jean-Louis Chéray led the debates that followed the screenings. He was the most generous programmer; his eclecticism was a form of active curiosity. I didn’t always have the same taste in films as him, but at least you knew that there were going to be surprises and disappointments. And that was a good thing. He was capable of showing us a Duvivier and a Boetticher in the same screening session, and people were committed to the discussions that ensued. When he was convinced that something in a film was good, he would stand facing us, pointing to the screen behind him, exclaiming: ‘It works, eh!’ What the filmmaker wanted to express by their mise en scène was, well, expressed for real. When Chéray said ‘it works’, he said all there is to say about a sequence being successful. Earlier, I spoke badly of professors, but Henri Agel was one of those rare ones who demonstrated open-mindedness: he defended Ford, Hawks, and Minnelli at a time when they were defended only by film enthusiasts. In his ‘ciné-club du Louvre’ on rue de Rivoli, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, he was very combative.

S. Toubiana: Did you feel that you were part of the moment when the Nouvelle Vague was emerging around Cahiers?

J.-C. Biette: Absolutely not. I quickly had the feeling that favoritism was present. While I suspected Godard was great, I was hesitant to go see his films. It disturbed my passion for American cinema; at the same time, I sensed that, sooner or later, I had to get to him.

The wish to write for Cahiers came naturally. Encouraged by that good Saint Peter that was Jean Douchet, but very intimidated by Éric Rohmer who was taciturn and looked like Goethe, I performed the sacrificial rite of visiting the antechamber at the Cahiers office, situated above the ‘George V’ cinema. I dropped by from time to time to see Douchet, who always took me to the hallway where, seated on a deep armchair, I listened to his analysis of the latest Renoir or Fritz Lang. Besides Douchet, Rohmer was nonetheless the only one I dared to speak to because his very literary style as well as his surprising and audacious taste amused me enormously. He was also the first filmmaker from Cahiers whose films I liked and whose cinematographic project I admired, and which consisted in saying: I am doing this and I stand by it. I came to like Godard’s films a bit later, when I discovered Rossellini.

S. Toubiana: There was what was called ‘Mac-mahonism’, a tendency of which you were part, I believe.

J.-C. Biette: I was a bad student of Mac-mahonism. I felt uneasy about this current, but I really liked the filmmakers it defended. However, I’ve always found their ‘Four Aces’ [Carré d’As] bizarre: Lang, Preminger, Walsh, Losey. The latter seemed to me much closer to the moderns, and I found that fascination [1] was only rarely present in his mise en scène. Moullet’s article on Time Without Pity, in which he wrote that the film did not address the themes of Mac-mahonism, made me laugh because he was right.

Michel Mourlet’s article, ‘On a Misunderstood Art’ [Sur un art ignoré], published in Cahiers, was in a way the manifesto for Mac-mahonism. It left a mark on me: it mentioned films that I hadn’t known and that I could go discover in local theatres: Lang’s Der Tiger von Eschnapur and Das indische Grabmal, and Walsh’s The Naked and the Dead. His article was not only well-written but also had something essential and novel at the time of its publication that I find still valuable today.

J. Narboni: It is an important article because it was one of the first to define not a cinema ‘in and of itself’, which many people before him had done, but mise en scène ‘in and of itself’: an attempt to define the specifics of mise en scène, which is a very different task. Mourlet went to the heart of the problem, even if one didn’t agree with everything in that article.

J.-C. Biette: I barely knew him. When I first started reading Arts, Douchet was at the helm of the cinema column. Truffaut had stopped writing by then. I saw Les 400 coups right when it came out. For me, he was someone who didn’t have precise or familiar features. Someone like Luc Moullet, on the other hand, was more familiar to me. It was a generational issue. His study on Fuller, a filmmaker who often shot feet, made a splash, and his article on Godard was brilliant and premonitory.

S. Toubiana: How would you characterize the era from the late fifties to the early sixties? Do you find it stimulating, joyful, with great debates and conflicts?

J.-C. Biette: It was a very stimulating experience for me. Essentially, life consisted of discovering cinema. It was what helped me forget the distressing years spent in high school and college.

S. Toubiana: It was also the time of the Algerian War: how did it affect you as a high schooler, on one side, and through your love of cinema, on the other?

J.-C. Biette: It preoccupied me more when I was in high school. I was in philosophy class: there were people on both the left and the right. I was a left sympathizer, but with reservations, a reticence when it came to collective action. I always had trouble with groups. I know I’m in the wrong. Life teaches us that we have to be many to wage certain struggles. Cinema-wise, the films that spoke to me were Le Petit Soldat and, to a lesser extent, the films of Claude Bernard-Aubert, whose Les Tripes au soleil — perceived as anti-colonialist — I now remember as having been not particularly good, but very violent. I discovered Positif through its coverage of the Algerian War and the way it defended committed cinema.

J. Narboni: Comolli had come back from Algeria three or four years before me. The first screening I attended in Paris was of Petit soldat at the Sorbonne, organized by the UNEF [Union nationale des étudiants en France], during which Godard was accused of being a fascist. I didn’t fully understand what was happening at Cahiers, but I think there were multiple positions. Truffaut had signed the Manifesto of the 121, probably more in opposition to the army than out of anti-colonialism, but the general position of the magazine was at best apolitical and, at worst, right-wing anarchist. Rivette, because of his leftist opinions, including in cinematic matters, was the only one to be spared from the attacks and violent insults coming from Positif. As much as À bout de souffle, Le Signe du lion, and Chabrol’s first films — Les Cousins and Le Beau Serge — were criticized in Positif, Paris nous appartient was considered a leftist film.

I was struck by the fact that, in the dictionary of the Nouvelle Vague published in issue 138 of Cahiers, the last entry was Octobre à Paris, a film about the repression of Algerians in Paris in 1961, credited to X (I think Armand Panigel was its director [2] ): there were ten favorable lines about how the film was ‘a deeply moving document’. I was very surprised to read that in a magazine that was marked by a haughty conservatism. Godard’s films, up until Pierrot le fou — Les Carabiniers, Le Petit Soldat — were considered nihilistic; Paul Gégauff played an important role, a film like Chabrol’s Les Bonnes Femmes was seen, foolishly, as a fascist film…

There was, in the name of mise en scène, a considerable reticence about ‘committed cinema’ that didn’t question form, contending itself with the message.

S. Toubiana: Your first text was published in Cahiers in 1964, at a time when Rivette was the editor in chief, succeeding Rohmer.

J.-C. Biette: Before I started to be published, I wrote a lot — for myself, in order to see things clearly — about films I liked or questions I had about cinema. I recall an article in which I compared Hawks’s Hatari to a newsreel film on the Vietnam War, but in the sentimental vein of Rohmer’s text on Marcel Ichac or Godard’s text on Haroun Tazieff. I was far from suspecting how important the Vietnam War would become and how unimportant Hawks’s film was to become for me. I never stopped writing, in the hope that one day I would be published. At the time, Cahiers was almost confidential because cinema didn’t yet have the mediatic aura that it’s had in recent years. Later, I was impressed by the numerous notebooks Jean-Claude Guiguet filled, far from Paris, with notations on films he liked, without being impatient to be published. I’ve always thought that real reflection begins only when we submit ourselves to the test that is writing. Rivette accepted an article I wrote about Gance’s Cyrano et d’Artagnan and later asked me to write more articles. Before that, in 1961, I had shot a short film in the Baie de Somme: I didn’t tell anyone about it, it was a strictly personal affair, like writing a poem in a corner. The subject being autobiographical, the only point of the film’s content was for it to be an exorcism. It was a pretext to film people, landscapes: a silent short shot on 9.5mm film (the story of a young man chasing a couple) that was lost. When I started writing, I tackled films rejected by the new editors — Comolli, Narboni, Jean-André Fieschi, Bontemps — who no doubt worked more ardently on writing, thus saving the important films for themselves. I was determined to write and to make films but at my own rhythm and by taking my time.

Raoul Walsh with Pierre Boulez

S. Toubiana: That era of Cahiers was characterized by modernity: the magazine published interviews with Barthes, Boulez, and Lévi-Strauss during that time. Did that not clash with your taste for American cinema and the filmmakers deemed ‘minor’, like Dwan and Tourneur?

J.-C. Biette: In fact, I didn’t like Tourneur at the time, to the extent that he was clearing the decks of Hollywoodian conventions; it was too audacious for me then. I didn’t understand him. I didn’t like Allan Dwan very much either, only his sense of landscape. Above all, I liked Walsh. We discovered Ford around 1963–1964, during a big retrospective in Ulm that notably included a projection of The Wings of Eagles, which upended the anti-Fordism of Cahiers.

Prior to that, I especially liked Lang, Walsh, Hawks, and, to a lesser extent, Hitchcock, whose North by Northwest and The Birds — which had just come out at the time — I liked, but less so than Lang’s films. I also liked Nicholas Ray andPreminger, but not all his films: I remember that I hated The Cardinal but really liked Exodus. Once again, it’s a question of light, which was the first absolutely insurmountable obstacle in The Cardinal for me. I found the light in Exodus very moving: it signified the transparency of the gaze.

J. Narboni: Just as Rivette arrived, Cahiers was putting a ‘damper’ on certain filmmakers, including Minnelli and Preminger, in the name of modernity. Some editors, including Douchet, still came to their defense. On the other hand, filmmakers like Antonioni, and above all Buñuel, took center stage. The major modern films became El ángel exterminador and The Birds in the name of a theoretical notion that came both from Barthes and the nouveau roman: ‘suspended meaning’, that is to say films that had an unresolvable enigma that all interpretations fumbled — an enigma that beckoned all interpretations yet ruined them all. This was a core point at the time in the pages of Cahiers.

J.-C. Biette: Modern art forcefully made its way into Cahiers, with frequent references being made to Lévi-Strauss, Barthes, and Boulez. So I followed fashion, though I had discovered Boulez before encountering Cahiers: I admired him infinitely. Some of us went to the Domaine Musical concerts. I looked forward to Stravinsky’s latest works as I did John Ford’s films. I remember the day of 18 June 1963, when Jean Narboni and I went to the Cinémathèque on rue d’Ulm to see Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu. Later that night, the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées held a Stravinsky concert directed by Boulez. The emotion produced by Mizoguchi was such that we doubted the intensity of the concert: ‘The Rite of Spring’ [Vesna svyashchennaya] wouldn’t hold up after Mizoguchi. Well, Stravinsky and Mizoguchi stood side by side. This equality, too, was the greatness of cinema.

J. Narboni: We can say that there is a cinema that joins itself to the world, that is in the world, that doesn’t rival the world, or at best restores order in the idea of the world: this is the great classicism, according to Rohmer. On the other side, there are filmmakers who rival the world, filmmakers who have their own universes that are equals with the world, thus deforming appearances by constructing other ones.

This is where the division lay for me: the splendor of the real, of the world, against an auteur’s demiurgic reconstruction. That was what the discussions were about, even if this division was too crude, because someone like Rossellini cut across it. Mizoguchi was the absolute model of the former, in contrast to Kurosawa, whose cinema was dislocated. In literature, it was Goethe versus Kafka.

J.-C. Biette: There was this idea of universal harmony, even if it contained a lot of violence. There was also the fact that the world had changed a lot in a few years. I started reading Cahiers in 1958–1959, and that period is for me the end of Hollywood. A filmmaker like Lang made his films on the basis of the so-called universality of cinematic language — perceived as such, in any case. This so-called universality started collapsing, however; you can see it in the final films of John Ford. A film like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was immediately seen by us as a modern film and not merely as another western. There came a time when a system of communicating vessels emerged, in which European cinema (Antonioni, Bergman, and others) eventually became substantial, and in which the new language of cinema was that of the moderns: not only Antonioni and Bergman, but also Fellini and Pasolini, were starting out. That kind of cinema became so alive that it had to be considered the new gangue from which cinema would be born.

That era was absolutely extraordinary: at the Champs-Elysées theatre, we were watching Dreyer’s Gertrud, Antonioni’s Il deserto rosso, a Ford film, The Birds, and Sternberg’s Anatahan, all at the same time.

S. Toubiana: Essentially, you were writing very little during the mid-sixties.

J.-C. Biette: I remember people fighting over which films to review each month, and I was very bad at that.

S. Toubiana: How did you spend your time then?

J.-C. Biette: I was in college because my parents made me stay there. I tried to get a degree in literature, which annoyed me. But I watched a lot of films, but that didn’t necessarily lead to much writing. In 1965, faced with my military service, I preferred to go to Italy. It was the year when the new Italian cinema (with Bertolucci, Bellocchio) was being discovered; I had just discovered Straub in Locarno, as well as Pasolini’s first films: Il Vangelo secondo Matteo, Accattone. I felt that cinema was taking place in Italy.

Roman Poems: 1965–1970

S. Toubiana: That Eustache’s first films came out in the middle of the Nouvelle Vague is a paradox…

J.-C. Biette: I felt I had nothing in common with the people from the Nouvelle Vague. And by the time I left, Eustache had made only one film. He was already a lone fighter. I felt I was suffocating in Paris and, on the day I was supposed to rejoin the French army in Baden-Baden, I decided to take the train to Rome.

J. Narboni: I remember your father coming to the Cahiers office to ask where you’ve been. There was a missing person appeal, and we saw your face on ‘Journal télévisé’, presented by Léon Zitrone; it was as though you were a criminal.

J.-C. Biette: It was treated like a runaway incident, a youthful indiscretion. I was the most unorganized of rebels.

On my second day in Rome, I visited the set of Pasolini’s Uccellacci e Uccellini. Later, thanks to Gianni Amico, who made documentaries, I met Bertolucci; and there I was in Rome for four years. It was a much richer experience than the one I had at Cahiers, where I had written but a few impersonal articles, and where I felt marginal. In Rome, I discovered that filmmakers talked to each other, saw each other often, and, most importantly, that life incessantly invaded and nourished the films. Not to mention meeting Pasolini.

I started work on a Gian Vittorio Baldi’s project for a film magazine, edited by Adriano Aprà: a ‘new cinema’ magazine devoted to Canadian, Brazilian, Czech, and French cinema, and which was supposed to be published in different languages (I think only one issue came out). Louis Marcorelles introduced me to Baldi, and because I was at Cahiers, he produced a short film of mine: I started shooting, taking my time — I filmed on the days I felt like filming. The editing process was equally piecemeal. Eustache edited the second part. To prepare for that magazine, discussions were held at Baldi’s production studio. Rossellini joined several times. I was amazed by his vitality: he cleared obstacles with a simple sentence. Bertolucci joined more frequently. I met him upon his return from Iran and Egypt, where he was making a film on oil transport: La via del petrolio. He told me that Pasolini was looking for someone to teach him French. At the time, Communications was publishing texts by Christian Metz and Barthes, and Pasolini wanted to read them in French. We went regularly with Aprà to Pasolini’s house in the afternoon, where we would read these texts together. That’s how I came to correct Uccellacci’s subtitles for the Cannes Film Festival. I later worked as an assistant on Edipo re, but I was bad at it. One day, when Noël Simsolo asked Pasolini what I was worth as an assistant, Pasolini answered: ‘He assists.’

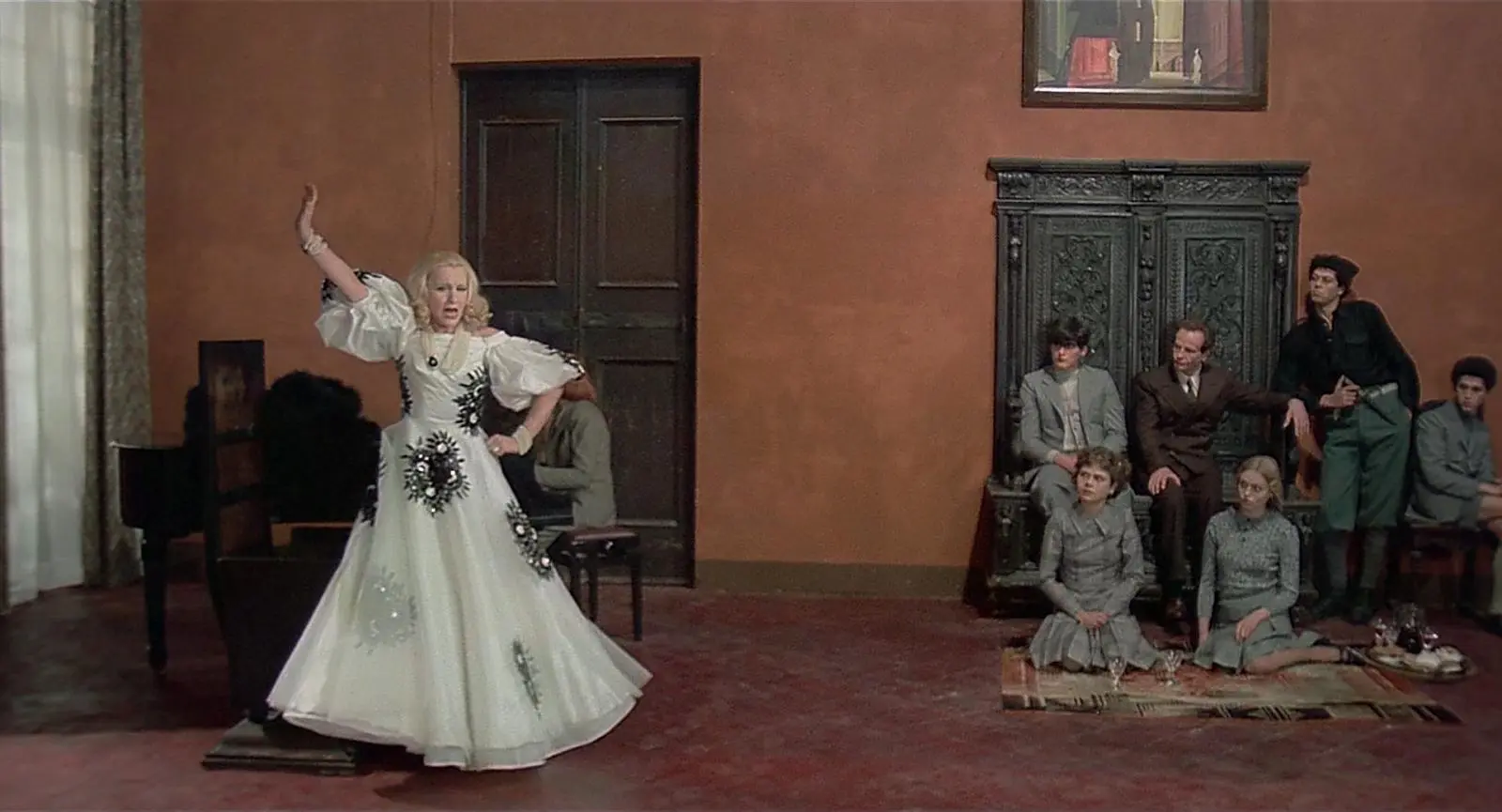

At that time, around 1966, Bertolucci had many film projects. On the way back from Cannes, in the car, we talked a lot: we had time. After falling asleep for what must have been an hour, I woke up and he started telling me a story that came to him while I was sleeping: he called it ‘Natura contra natura’, a great title. He later wrote it for Jean-Pierre Léaud, Allen Midgette who played the American soldier in Prima della Rivoluzione, and Lou Castel — but he never made the film. He always had stories he was developing, projects he couldn’t bring to fruition. In 1967, after directing a sketch with Julian Beck and the ‘Living Theatre’ about the parable of the fig tree, he succeeded in securing financing for Partner. It was in the middle of May ’68: we heard about what was happening in Paris through Pierre Clementi, who acted in the film. During one of the many protests that took place in Rome, echoing those in Paris, an effigy of De Gaulle was burned in front of the Farnese Palace.

In the summer of the same year, those who were part of May in Paris came to Rome to change their minds or to at least rest. It was in this context that Godard’s Vent d’Est came about: Ferreri, Marc’O and his actors from Les Idoles, Cohn-Bendit, and Gian Maria Volonté were here, and I remember seeing people in Rome, in separate groups, worried that they’re going to bump into each other. The atmosphere was very tempestuous. One of the best experiences I had that had to do with the relationships between cinema and politics took place at Aprà’s ciné-club, ‘Filmstudio’, where Straub’s Der Bräutigam, die Komödiantin und der Zuhälter was screened: Cohn-Bendit, surrounded by his friends, had attacked the film. For him, war and capitalism in cinema meant watching tanks in Vietnam and showing them in the shots, and he accused Straub of showing nothing. Straub responded by saying that he doesn’t make films for the students, but for the ‘Cinéac’ cinemas at the railroad stations, for the prostitutes and the pimps. The conversation came to a sudden halt.

Pasolini was also attacked by students and far-left movements; he reproached political films for being only half-political, for being, in fact, political fiction, for making political reality novelistic; and no one, neither those who made these films nor the ones who went to see them, wanted to admit that. It was the period when he made Teorema and then Porcile, which went in the direction of metaphor, of symbolized conflicts, that is to say in the opposite direction of the political films of Francesco Rosi and Elio Petri. It was a time of loud polemics, everyone was taking stances on what cinema ought to show: commitments were crystal clear in the realm of politics. You could see this in Venice, where the debates were turbulent, where Pasolini was attacked by the students. But he stood his ground, mounting his arguments firmly and stubbornly, trying to understand them and make himself understood. I never saw this in anyone I met, not to this degree. He was stubborn but infinitely patient.

I came back to Paris in late 1969 and continued working with Pasolini whenever he visited to work on the subtitling and the French-language version of his films (looking for specific voices, etc.): Il Decameron, I racconti di Canterbury, Il fiore delle Mille e una note, and, later, Salò. The last time I saw him, he had just called Piccoli for the dubbing of Salò and was going to have his final interview with Bouvard. It was the night of his assassination.

Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

The good excuse of ideology

S. Toubiana: Coming back to Paris, what difference did you find between the frame of mind that reigns in Paris and the one you experienced in Rome?

J.-C. Biette: It was very different, much more on edge, people rigidly held on to theoretical positions and tended to force reality and films into gridlock. People came down against certain films that were ostracized based on outside accusations. There were two filmmakers who were never rejected by Cahiers, no matter how harsh the positions were: Godard and Straub. On the other hand, there was a general rejection of the filmmakers of the Nouvelle Vague, considered to be ‘bourgeois’ and ‘old-fashioned’: Rohmer, Chabrol, Truffaut suddenly became remote. At that time, the important filmmakers were Eustache, Garrel, and Rivette. Out 1, released in 1971, was deemed Rivette’s most audacious project; Eustache wanted to make films but couldn’t — this was when he was making the film about his grandmother, Numéro zéro. The filmmaker who seemed important to me at the time was Adolfo Arrieta, who never stopped filming, simply because he had a portable camera on hand; shooting was part of his daily life, he had an editing table facing his hotel in the Pyrenees, and he stayed up at night to edit. It was very stimulating because making films in such an artisanal and poor man’s fashion, as Arrita did, was frowned upon: it was seen as a bourgeois activity that had no legitimacy unless radically expressed, in the manner of those like Godard and Straub. Arrieta wasn’t radical. Almost nobody took his films seriously, but he was Cocteau’s cinematic heir, with films like El Crimen de la pirindola and Le Jouet criminel.

There was also Duras. It was before her first successful film, India Song, in 1975. She was a marginal filmmaker and took up the cause of a ‘different cinema’ for the sake of those who make low-budget films. In ‘free’ cinema, of which Duras was the great guardian, it was felt that ‘resistance’ was being practiced.

This kind of cinema was being screened every year at the Festival de Toulon, which later became the Festival de Hyères, featuring an experimental, non-narrative section, often inspired by the American avant-garde of the mid-sixties: Kenneth Anger, Mekas, and others. A visual, extremely pictorial cinema. The two short films I made during those years, Ce que cherche Jacques and La Sœur du cadre, were shown in Toulon, with the latter film, which I consider less good, receiving the Prix de la Critique. It was a very theoretical film, which was why it impressed people, but it wasn’t good. I showed it to Pasolini, who was rather reticent and later said something extraordinary to me, on the street: ‘When you fail a film, it’s because you’re lying to yourself.’

S. Toubiana: Did you lose contact with Cahiers at the time?

J.-C. Biette: No, I walked by Coquillière Street regularly, but I remember this period as having been very sad, one where you mustn’t make a single wrong move.

S. Toubiana: For you, how was the old, pro-American cinephilia able to coexist with the current of ‘different cinema’ on one hand and the theoretical current in vogue at Cahiers, which attacked Hollywoodian representation, on the other?

J.-C. Biette: A significant moment was Cahiers’s study of Ford’s Young Mister Lincoln, which Eisenstein called one of the greatest American films — a film he said he would have been proud to make. It’s a very beautiful film, but I don’t see it as being more important than other Ford films. Besides, Eisenstein’s appraisal was just about contemporaneous with its release. To come back to the subject of American cinema, I was on the defensive, because I couldn’t find a way to talk about it in relation to modern cinema. I continued watching American films at the Studio Action theaters, but that cinema had become the past for me; I couldn’t see a way of reactivating it. I revisited American cinema following discussions with Daney and Skorecki, who talked to me about Tourneur because they saw commonalities between his films and my short films. Tourneur didn’t interest me in the sixties because he makes a cinema in intaglio, putting the imaginary to work starting from codes that he inverted, a bit like Hawks but in a less attractive way. For me, codes were signs of nature, and the moment they strayed from their principal function, I became frustrated. So, in this period of political reassessment and rejection of American cinema, someone who had a perverse relationship to the codified system became more interesting than the filmmakers who had a ‘glorious’ relationship to Hollywood. There are filmmakers, like Cukor for instance, who I never really liked because they went in the direction of glorifying American craftsmanship.

I wrote about Tourneur. For many years, I regarded him as one of the greatest filmmakers. I went to meet him in Bergerac and remember him as the most profoundly original man I have ever met among the filmmakers I knew and admired. He was indifferent to vanities. He probably did not make the most important films in the history of cinema. He had no artistic ambition or personal wishes. Yet he possessed, more than anyone else, the secret of cinema. He was a calm clairvoyant who knew everything about life and who perhaps thought that it is enough to let his films suggest that. He tried to almost devalorize his films or to say that he had nothing to do with them. Which is almost true.

S. Toubiana: This period between 1968 and 1970 is fundamentally paradoxical, marked by the coexistence of multiple discourses on cinema: the cinephilic discourse, the defense of new cinema, the Marxist or, more generally speaking, theoretical (semiological, psychoanalytic) approach. It is very difficult to trace.

J.-C. Biette: For youngsters like me who were making short films, the materiality of film was a rather powerful idea. What I liked about Rivette’s films is the grain of the image and the documentary recording of aleatory events, something one found already in Echoes of Silence, by Peter Emanuel Goldman, a major sensation at the Pesaro Film Festival in 1966 that shocked Eustache, Straub, Bertolucci…

Cinema was, in part, the succession of multiple young national cinemas: Brazilian, Canadian, Czech, in 1964–1965, with direct sound being important. We liked hearing noises from the streets in the shots — a pleasure in recording the ‘crackle’ of life. Renoir, who admired Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, lamented the film not being shot with direct sound. He said so to Glauber Rocha.

J. Narboni: The point in common between experimental cinema on one hand and the theoretical discourse on the other was matter: the rejection of transparency, of smooth, harmonious cinema, in the name of everything that clashes with harmony and ruptures the flow. From matter to materialism, we quickly took the plunge.

No more dogma: Jean Eustache and Paul Vecchiali

S. Toubiana: We should talk about La Maman et la putain, which marked an important date: 1973, a time when Cahiers was split between the love of cinema and their dogmatic political discourse. It is an important moment of fracture for the magazine.

J.-C. Biette: I saw Eustache frequently at that time and observed the writing of the script and the shoot. While he was writing the script, Eustache kept a copy of À la recherche du temps perdu by his side. It would be interesting to rewatch the film with this shadow of Proust hanging over it. No one thought it would go on to become the historical film it ended up being.

S. Toubiana: During these political years, you didn’t write much about cinema.

J.-C. Biette: I felt like there was nothing I could write about; I had neither the desire nor the strength to start from political or structuralist presuppositions. And at that time, I didn’t have a comprehensive idea of cinema. I tried to figure things out by making short films.

1974 was the year Paul Vecchiali’s Femmes femmes came out. The film placed an importance on the performances of the actresses, as well as a certain theatricality. It was novel and very lively. I had sometimes noticed that Vecchiali was a marginal figure in relation to Cahiers. For me, he was a cousin of Eustache. I barely knew him. People knew that he was a graduate of the École Polytechnique and that he crossed paths with Cahiers at some point. (He wrote, among other things, an article on Procès de Jeanne d’Arc). Femmes femmes was a landmark film that, contrary to La Maman et la putain, was not recognized; it became a secret classic. Very few people went to see it, but I sensed that it opened doors, that it was a manifesto against the complacency of the auteur. In the potency of Femmes femmes, there lay the possibility of moving towards a cinema that incorporates the pleasure of acting, a dimension that had been missing from the cinema that we liked at the outset of the 1970s. This dimension exists in the film through the actors, who became at once the content and the expressive and stylistic propositions of the film. It responded to a felt need, following a period that had instead been marked by a neutrality in acting. Pasolini, who was overwhelmed by the film at the Venice Film Festival, cast the two actresses, Hélène Surgère and Sonia Saviange, in his next and final film, Salò: they even reenacted two moments from Femmes femmes.

The following year, I wrote Le Théâtre des matières, which I directed in 1977. What is most difficult, when making a film, is not so much the technical aspect but the actors’ approach: the real difficulty of cinema starts here. How to bring about and distribute this reality of the actors in relation to how we imagine the characters, how to know what belongs to the one and not the other: this is where the mystery of cinema begins. Towards 1977, notions of historical materialism and the political positions taken by films were suddenly relativized by my discovery of the importance of actors in a film. I also had the impression that many questions of style were suddenly less important. But perhaps all of this was of concern to nobody but me. In any case, it wasn’t a general movement.

To each film its own poetics: 1977–1980

S. Toubiana: The paradox is that you rejoined criticism right when you started making your first feature film.

J.-C. Biette: Yes, I felt like writing about cinema again. I felt that this coincided with a need, at Cahiers, to reconnect with the cinema that the magazine had defended in prior years and the desire to interrogate what constituted the ‘poétique des auteurs’, meaning Hawks–Hitchcock, Renoir–Rossellini, and above all the two filmmakers that really mattered to our generation: Ford and Lang. Ford, in as much as he was a filmmaker one pitted against Hawks, both of them having made westerns and action films. If Rohmer had always put Hawks on a pedestal, Ford was, for some of us, a greater filmmaker. He remained so for me.

S. Toubiana: The seventies, it appears to me, were very ecumenical and consensual when it comes to the History of cinema: except for some rebels, everyone essentially found their places. How do you read this tendency that followed the period of great schisms — violent, theoretical, and ultra-political schisms — that was 1968?

J.-C. Biette. The seventies were marked by the new generation’s desire for rediscovery combined with the phenomenon of the re-release of old films, which happened less via the ‘politique des auteurs’ than via an interest in actors. It is also a major period for film series programmed by the ciné-clubs of Claude-Jean Philippe and Patrick Brion on television, which comprised very rare films. Cahiers also had the idea to re-evaluate old films, to reclaim the history of cinema: hence the column called on films playing on television. But that idea was minoritarian and almost paradoxical. I was, however, struck by the fact that, upon revisiting the history of cinema, there was, on the part of both the public and critics, nostalgia for the most dated professionalism and cinematic craft. Having been part of that, I can see that there are always a number of clichés that accompany the reception of films, and these clichés also exist when it comes to old films. One must always ‘do the housework’: the histories of cinema are rife with films that have made the cut either because they were commercially successful — and their success was held as a marker of quality — or because they were acknowledged for reasons of moral and aesthetic comfort as well as critics’ identification with them at the time of their release. I had the desire, almost ‘quixotic’, to remake my own history of cinema.

J. Narboni: In this ‘reunion’ you’re talking about, Wim Wenders played an essential role. In 1977–1978, there was the equivalent of what La Maman et la putain had been for the ’68 generation: the dérive, the end of ideology, silence. However we may feel about him, Wenders fought for these reunions with cinema in his capacity as a cinephile, making a detour via Nicholas Ray and Ozu. He played a major role in reconnecting these two threads, returning to the cinema of an entire generation, passing through America: Ford, Ray, Fuller. From that point of view, Im Lauf der Zeit became a landmark of that period. I wonder whether, after years of rebellion, criticism, and discourse ‘against’, Wenders wasn’t attuned to desolate affects, a wish to wander out of ideologies and their contradictions.

J.-C. Biette: It was very different from what happened with La Maman et la putain, or in the sixties with Godard. With Wenders — in my opinion, his immense success comes from this — there is no critical dimension. He is a sentimentalist who assimilated a whole American sensibility that came from the cinema of Nicholas Ray: hence the European public’s widespread identification with it. Except that Ray’s cinema was critical — if not in its form, then at least in its characters. I often quote this sentence by Fritz Lang: ‘All art must criticise something.’ At that time, Fassbinder was rejected, but it is in his films, most of them, that we can find this violent, critical dimension: from Angst essen Seele auf to Querelle…

‘Cinema-chronicles‘: 1985–1986

S. Toubiana: To wrap up, let’s turn to your ‘Cinema-chronicles’, the last series of articles you wrote for Cahiers…

J.-C. Biette: All alone in my corner, I bemoaned what was happening in cinema, and I suggested to you that we see each other, because I felt this desire to write again, to communicate — at the risk of coming across as bitter or violent — what I felt. You proposed the formula of a monthly ‘chronicle’, although I didn’t know if I would be able to produce a piece of writing each month. Some months, I wasn’t able to. The commission was to write about old films that I revisited as well as contemporary films. I liked doing it: naturally, I navigated between the past and the present, and it was a way of verifying my certitude that bad cinema is timeless, as is good cinema.

A work of art bears a number of meanings that we can decipher at any moment, because the present doesn’t arrive out of nowhere: the meanings put in motion by a film are not dead, they are always here, and they have followed a path in reality as well. We are always trying to talk, at the same time, about the past, the present, and the future: neither the past nor the present is in principle superior or inferior.

S. Toubiana: What mattered to me was: 1. No nostalgia. 2. Every old film is to be watched again according to the conditions of the ‘feasibility’ of its craftsmanship, rendering secondary the notion of the auteur, which tends to sugarcoat, even obscure everything. 3. To talk about a film by Garrel, Rossellini, or Oshima is first and foremost to place them at the same starting point.

J.-C. Biette: Yes, I watch them with equal interest and equal disrespect, without emphasis. I tell myself: here is someone who made a film, who doesn’t have, in principle, more value than someone else, and when I think about a film, I compare it to others by its author and to other films by other auteurs. It’s what I call, rather than ‘politique des auteurs’, a ‘Poétique’ expressed by the films, which can concern one film, several films, or an entire oeuvre. This poetics signifies a filmmaker’s personal vision and, at the same time, aesthetic practice or craft. There is no reason to dispel this permanent ambiguity. In cinema, there is a relationship that is very difficult to specify between conception and materialization. Criticism must try to elucidate this relationship. It’s not easy, but it’s what is already there in the work of our model, André Bazin.

I wanted, in these ‘chronicles’, not so much to attack films — what right have I to do that? — but rather to define the illusory opinions regarding certain films that provoked an infatuation or indifference that seemed unjust to me. Critics weren’t saying ‘this or that film is interesting and has this or that wonderful thing’. Instead, they were claiming that there is one masterpiece every few weeks! It would be enough to say that ‘good films exist today’. Living cinema is first and foremost about this: the possibility of talking about what is good in some films. By doing so, critics and filmmakers could see clearly and maybe also see or do good things in films to come. But the cinephilic public also bears part of the responsibility. Indifference is a crime that is indeed shared.

Interview conducted in February 1988.

Published in Poétique des auteurs (Éditions de

l’Etoile, Cahiers du Cinéma 1988), pp. 6–20.

Monkey Business (Howard Hawks, 1952)

Notes

Translator’s note: ‘The absorption of the mind in the spectacle is called fascination: the impossibility of wresting oneself from the images, the imperceptible movement of the whole being as it strains toward the screen, the abolition of the self in the wonders of a world where dying itself is situated at the extremity of desire.’ Michel Mourlet, ‘On a Misunderstood Art (1959)’, trans. by Gila Walker, Critical Inquiry, 48:3 (Spring 2022), 483–498 (p. 492).

Translator’s note: Jacques Panigel, not Armand Panigel, is the director of the film.