Among the twenty or so films made by the production–distribution–catering company Diagonale, founded in 1976 by Paul Vecchiali, Cécile Clairval and Pierre Bellot, are five features that are the first by their respective authors: Le Théâtre des matières (1977) by Jean-Claude Biette, Les Belles Manières (1978) by Jean-Claude Guiguet, Simone Barbès ou la vertu (1980) by Marie-Claude Treilhou, Cauchemar (1980) by Noël Simsolo and Beau temps mais orageux en fin de journée (1986) by Gérard Frot-Coutaz. The first three, which for me remain unforgettable (Simsolo’s film is forgettable, Frot-Coutaz’s is a little less startling), have ended up establishing themselves as a discreet but decisive point of reference in the force field of cinephilia, defying their modest economic origins, lack of contemporary recognition, and the more or less lengthy periods of invisibility imposed on them by the laws of the market. [1] To say that I love this trio of miraculous films immediately signals, I think, what my relationship to cinema is all about: not filmmakers’ demonstrations of skill, moral rectitude or social concern; even less the finish of works, that art of flawlessness animated by the desire to please, where cumbersome writing and visual surfeit disguise a fear of negligence; and least of all those patronizing efforts by films to point me out, safeguard me, earmark me through nudges and targeted appeals for a neat place in a tailor-made plot. One doesn’t admire these films by Biette, Guiguet and Treilhou: one loves them. Not all at once, often not even on the first viewing, but through a difficult feeling that develops over time and passes through the shadowy zones, hidden nooks and air pockets of these films, soon to be coupled with the desire to see them again.

Simone Barbès ou la vertu (Marie-Claude Treilhou, 1980)

Returning to them, periodically rewatching a scene, a shot, or a gesture, drawing on the inexhaustible depth of detail, I gradually came to gain a sense of the gaze that guides them and to discern the awkward, tender, slightly anxious assurance of these debutants. Biette touches me when, as if to exorcise his fear, he begins his film with a silent ending, plunged into the artificial, interior night of his Théâtre des matières. His film opens on a double Langian title card, made out of actual pieces of card, announcing that it is the ‘Last Performances’ of Pelléas et Mélisande at the Théâtre des matières, a card which, in the stream of information it presents for decipherment, indicates the attention and humor we’ll need to bring to the film that is announcing itself. The camera then pans down to the cloakroom attendant (Denise Farchy), who is forced to duck under the jammed flap of the counter. She clumsily exits through a black square set against a red background, as though through a mouse hole. Enter Hermann (Howard Vernon), who switches off and puts away the pitiful little light-up Christmas tree on the counter, adding a touch of sadness to the quiet of closing time. Second shot: the camera lurks in the darkness of the theater, gliding as it follows Hermann, who closes a couple of doors on it, casting it into darkness each time, before it overtakes him and emerges into the light of a third door, still open, revealing a woman (asleep, dead?), Dorothée (Sonia Saviange), lying on a flight of stairs, like another clue in the riddle of this opening. In this shot, Biette transfers his debutant’s fear of the dark to his spectator: I move forward in his fiction, blindly navigating a space not yet defined, trying to identify exits onto meaning. In the manner of the jammed counter flap, this labyrinthine film constantly presents lights as so many false leads, dead ends, or blind spots. Even the ending is closed off in this film that plays with flat tints: the red and black of the beginning become the counterpart of the terrible white of the final image, when the camera leaves Dorothée, her three friends and their crêpe tea to the lightness of a flute from Bizet’s L’Arlésienne, to float towards a window opening out onto a blind wall. The image freezes and the (rather ugly) neon green credits quickly scroll over the creamy white of the wall, a white without destiny, a sort of inversion of the ‘white of origins’, which seems to wipe out the imaginary future of the characters. Biette’s façades puzzled me for a long time (his next film ends on a beautiful trompe-l’oeil fresco), until I realized their function: to make it impossible to imagine a sequel, to protect the characters. Le Théâtre des matières is a pyramid sealed from within. We can dive in again and again at our leisure, but we cannot maintain the illusion that its characters continue to live their imaginary life beyond the confines of the film, that we could take them with us like mythemes, that their fate could belong to us. Biette’s characters belong only to his fiction. Amid the countless details, objects and passwords amassed in this film where everything seems endlessly connected, the characters call to mind the pieces in that peculiar chess game Brecht dreamed of: ‘A game where the positions don’t always remain the same; where the function of the figures changes when they have stood in the same place for a while — then they would become either more effective, or perhaps weaker. As it is now, there is no development; it stays the same for too long.’ [2] None of these characters could ever be said to stay the same: caught in a web of relationships, changing function according to place, their valence exists only in the context of their situation. Hence the distance, of such a peculiar kind, between these characters and their spectator, which prevents identification while at the same time allowing for a constant surprise at their capabilities.

This proud defense of the autonomy of characters, rooted in the actors’ morphological and vocal characteristics, remains an admirable constant in Diagonale films. Each of them has taken me through ‘the incredible variety of human types’ (as Biette said of Murnau’s Der letzte Mann), bringing together these unique and wildly ordinary actors and actresses, who span the full range of physiognomies and ages, and whom we are sure to reencounter from one film to the next. Often discreet on screen, these actors possess inimitable voices. Like those of Duras, Straub, Guitry and Godard, these films gradually develop a particular sensitivity to the timbres, silences and varied intensities of voices, to echoes and rhymes, to the choppy, biting or awkward undulations of accents (Howard Vernon in Le Théâtre), to banter (Ingrid Bourgoin in Simone Barbès), to lisps (Emmanuel Lemoine in Les Belles Manières), embracing difficulties in speaking or being heard, unrepentant monologues and songs that burst forth without warning, and the fundamental importance of music, its ability to move us, whether on stage, on a record player or on a car radio.

Le Théâtre des matières (Jean-Claude Biette, 1977)

The hand-to-hand combat of reality

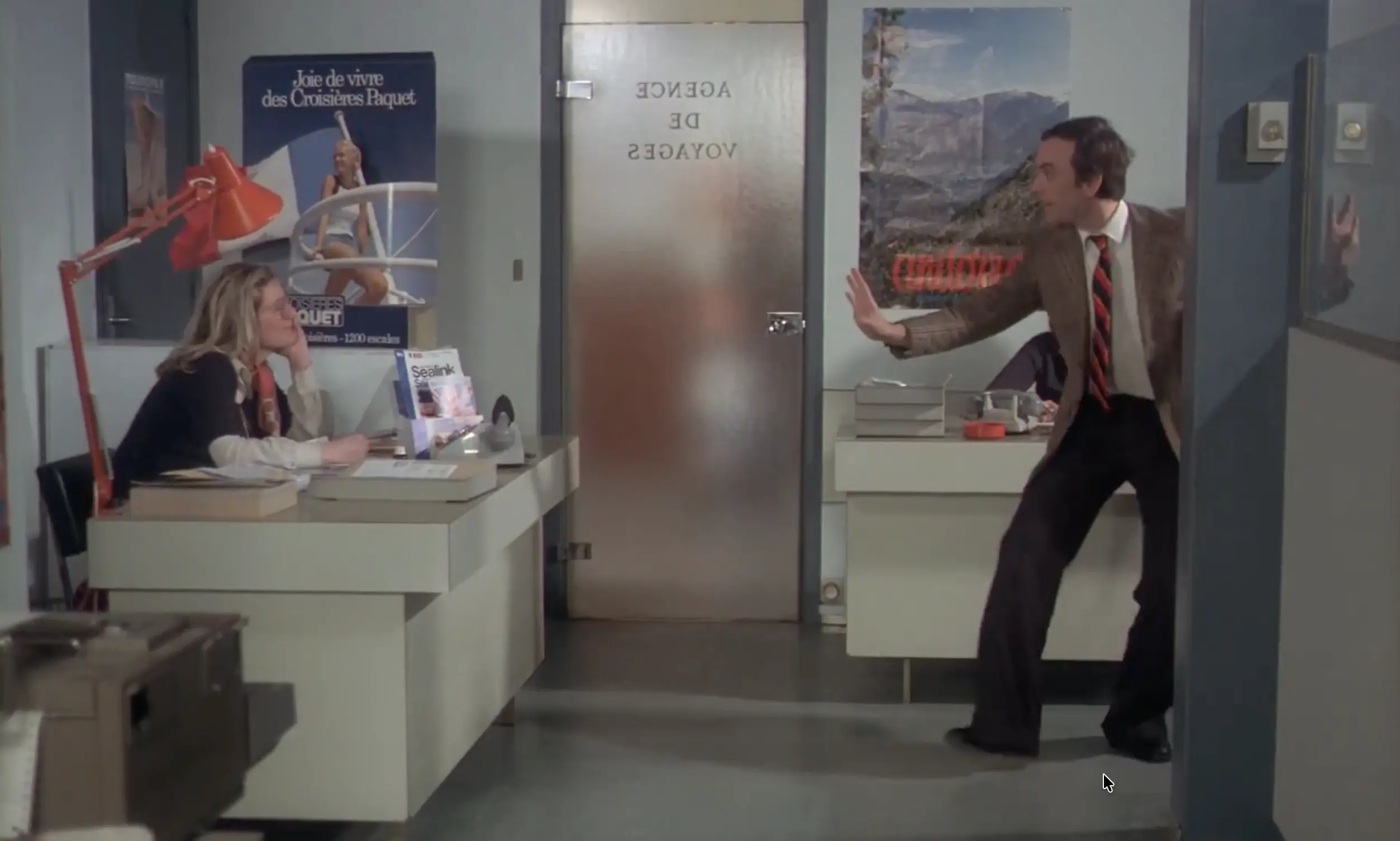

The guys of the Nouvelle Vague filmed friends the same age as them, while the post-68 filmmakers went in search of the elusive figure of the proletarian. But for Diagonale, in the late 1970s, as the great classless utopias were being mourned, it would be that disdained part of the petty bourgeoisie, that unremarkable, supposedly humdrum lower-middle class, poorly understood in fiction and life alike and more déclassé than any other, without responsibility or respectability of its own, generally only mentioned and represented as a mass. The beautiful common denominator of Diagonale productions, following the example of Vecchiali (who, for his part, reconnected with the French cinema of the 1930s), is the love, one by one, of these ‘average’ characters, forgotten by fiction. Where else but here could I see Denise Farchy, a little woman with a quavering, high-pitched, finely enunciated voice, who moves me just as much in the role of the cloakroom attendant in Le Théâtre as she does as the poor newspaper seller in Les Belles Manières and the lost pilgrim in Treilhou’s Lourdes, l’hiver? It’s not a question of ‘representing’ a class onscreen out of political decorum, but quite simply of showing people who are loved in real life and are as such already bearers of fiction. ‘In the past,’ remarks Guiguet, ‘in cinema, the supporting characters who so perfectly embodied the small trades, all the people who made up the popular stock, were there to breathe life into the fanciful; they were the guarantee of the real. That reality has died. But what can replace it?’ [3] In Les Belles Manières, Guiguet has his answer: Emmanuel Lemoine (Camille). The first shot in the film ‘introduces’ its actor, who is making his debut, boldly presenting his face head-on. He fixes his gaze on the viewer’s own, then turns his head to the side (so we can clearly see the scar running across his face), walking alone along the platform at the Gare de l’Est where he has just arrived, his steps weighed down by a small bag (like Hitchcock’s Marnie), the last traveler crossing paths, unnoticed, with the laborious ballet of three train cleaners. Emmanuel Lemoine, who was making his first steps in Paris, made his debut in this film, having never acted before. His role was originally envisioned for a young woman, but Guiguet, having met him and fallen for him, reworked his film, which became in his words ‘an image of the bourgeoisie confronted with the face, the body, the reality of someone who doesn’t belong to their world’. Guiguet had initially thought of titling his film Les travaux et les jours (Works and Days). Emmanuel Lemoine’s stocky body carries the weight of the heavy-going proletarian life that has shaped him, which we only learn of in snippets, like the mysterious scar on his face. Camille does give an explanation (a drunken car accident and a surgeon who, unhappy with being woken up, deliberately stitched him up badly), but it remains mundane, unsatisfactory. The marks and frame of lived experience imbue this body — observed out of the corners of other character’s eyes as it undresses or steps forward in clothes that are too tight — with a distinctive aura. Everyone here has their share of mystery, but Camille’s cannot be told, holding close to a body that defies all the morphological templates of its time, a body that fascinates through the paradoxical ‘class’ it bears in this bourgeois environment: ‘Camille’s body is real without being contemporary or fashionable, it is ideal without being abstract. His appearance creates the vibrations necessary for a jolt, an awakening of the story’s novelistic structures. He is the one who revives and regenerates.’ As with Biette and Treilhou, although written, composed and scripted in advance (Treilhou, scared to death before the shoot, had planned her découpage shot by shot [4] ), it is the people and things, objects of affection drawn from reality, that give body to the film: ‘I didn’t need much imagination to move the story forward,’ says Guiguet, ‘concrete reality pushed things along by itself.’

But it’s not just Camille: Les Belles Manières opens and closes on two onscreen faces, two solitary figures moving forward. At the end of the film, as Camille’s Parisian journey, to which we’ve become attached, draws to a close, we see the procession of his body in the prison where he was locked up, with the veiled faced of Hélène (Hélène Surgère), the grande bourgeoise who had hired him as a domestic, had played at friendship with him without ever stepping out of her habitus, and had in her own way sucked the lifeblood out of him, without ever really realizing it. On set, Guiguet recounts, ‘Sometimes, just for fun, I would place a portrait of Hélène and a portrait of Emmanuel side by side — it’s incredible how much they told me; I could feel how these two animated faces, traversed with their respective energies, would enrich the substance of the film by giving it a new, unique, absolutely free, untamable reality.’ If the films of Biette, Guiguet and Treilhou retain for me the marvelous power of the unexpected, it’s because they reflect their authors’ encounters with these people, taken from reality, which the films restage. It’s not about improvisation but rather capturing or provoking the primordial energy of that inevitable yet unexpected tremor that every encounter brings about. Fiction as a series of individual frictions, Le Théâtre, Simone Barbès and Les Belles Manières are built from successive meetings between unique individuals for whom – as is the case for me watching them – it is always the first time. We are in a similar state of heightened attention, that of discovering and listening to the other, with all the awkwardness, silences and dissonance inherent in the undecidability of the encounter, everything that makes it so that when we are face to face with the other, we never truly know if we are with them. If the nature of the spectator’s position is to be displaced, then these characters, who are always on the margins of what they are observing, are also spectators.

'Femmes femmes', a flagship

What I had sensed vaguely in these films, before I could grasp it better, was that they extended, guided and echoed the energy of an earlier encounter, which transcended the private realm of the filmmakers to become the motor of their fiction: Guiguet with Emmanuel Lemoine and Hélène Surgère, Biette with Howard Vernon and Sonia Saviange, Treilhou with Ingrid Bourgoin, all three with Martine Simonet, Paulette Bouvet, and so many others… We must mention the meeting between Guiguet and Hélène Surgère, which dates back to the shooting of Vecchiali’s Femmes femmes (1974), on which he was an assistant. The film was made before Diagonale, and it’s here that everything began. Guiguet went on to write Les Belles Manières for Surgère, while Biette saw in Vecchiali’s film ‘the possibility of moving towards a kind of cinema that integrated the pleasure of acting, a dimension missing from the cinema we liked at the beginning of the seventies. This dimension existed in the film through the actors, who became the film’s very content, its expressive and stylistic propositions’. [5] Femmes femmes, shot in two weeks from a script co-written with Noël Simsolo, is something else, something more than a film by Vecchiali. For me, it is one of the most beautiful films in cinema, the most profound, moving and simple example of the power of impure cinema. Its beauty emerges through the poverty of its teeming yet precise black and white cinematography, which reconciles Lumière and Méliès, the French cinema of the thirties and the Nouvelle Vague, Corneille and clowns, Demy and Beckett. An ode to actresses and their ability to wrap fictions around themselves, Femmes femmes casts Hélène Surgère and Sonia Saviange as their representatives, the ‘two faces of this mythical Janus of comedy and decline’. [6] The film depicts two unemployed actresses living together in a modest apartment lined with photos of old stars, overlooking the Montparnasse cemetery. Two sublime failures, they perform for each other as a way of cheating death, drink heavily, and suffer from money troubles and fathomless melancholy. Two women, alone together and childless, an unreadable couple (companions, sisters, lovers, living and ghost?) whose shared life constantly morphs across a cascading series of tender and sadistic compositions, role-playing games and intimate dramas, ambiguous expressions and waves of despair, all driven by a Cocteauvian tragic engine. And this is where the miracle lies, the film’s brilliant idea: to invent the pharmakon of that thing called melancholy. [7] Amid déclassement, boredom, alcoholism, nostalgia, and failure, in the depths of the most profound indolence, the two women manage to conjure a frenzied drive to create: fiction, human connection, a flood of words and images more or less disguised — a celebration at once joyful and bleak, intimate and destitute, deathly sad and defiant, prosaic and mythical.

The epigraph from Albert Camus that opens the film (‘Yes, to live in truth, play a role’) echoes Hélène Surgère’s unanswered riposte, which became (according to Pierre Léon) the rallying cry of the Diagonale filmmakers and those they inspired: ‘All is true!’ The desperate vitality of a belief in fiction and its ability to muster creation in the very heart of failure, to open imaginary windows between the most constricting walls. Belief in fiction, but always borne by bodies. The film was conceived by Vecchiali and Simsolo in response to Yves Robert’s Salut l’artiste !, but also around Saviange and Surgère’s own failure to find roles. At the heart of Femmes femmes lies a figure both trivial and metaphysical: the unemployed actress. What is the creative power of a performer? And what remains of it when she no longer practices her profession, especially once she’s older? What is an actress to do with that useless tool that is her own body, her poor body, with her demand for attention that goes beyond simple narcissism and touches on the most material aspects of existence: to act in order to eat, in order to live? Femmes femmes always responds dialectically, continuously oscillating between Sonia and Hélène, between life and death, cruelty and joy, the tragic and the ridiculous, documentary reality and dumb show, up to the point of the heart-rending cries of pain from the dying Sonia at the end of the film, which Hélène mimics between laughter and tears. This is why ‘Everyone’s an actor!’ would become the other rallying cry of Diagonale and those who followed in its wake: the knowledge that fiction transforms life, that it doesn’t even need a film set or theater to exist, simply a third party — and even then, in the film, Hélène may be dreaming. The genius of Femmes femmes is in having shifted the center of creation from the writer–director to his actors, themselves en abyme in the role of ‘has-beens’ (Vecchiali’s word) who have stopped acting or are not ‘fulfilling’ themselves. An interminable labor of the negative, which finds its energy in the heart of indolence, creation intertwined with sterility, the present moment nestled within melancholy.

The inheritance of spectators

I mention this ambiguous film, with a finish as imperfect as it is refined, because it became a ‘flagship film’, ‘a secret classic’ (Biette), a template that others inherited immediately. Following a Vecchiali retrospective in Venice, right after seeing the film, Pasolini gave both of the actresses roles in Salò and had them literally replay two scenes from Femmes femmes (the clowns and the death of Sonia), acknowledging his debt to Vecchiali by inscribing the carnivalesque at the heart of his adaptation of Sade. In their first features, Biette and Guiguet split the pair, each taking one branch of the dramatic energy of Femmes femmes. Rather than forms or subject matter, they inherited the bodies and figural power of these two actresses who had become alternative stars after the sort of screen test that was the Vecchialian opus princeps and its labor of the negative.

In Simone Barbès I reencounter from Femmes femmes (filmed a few meters away in the same neighborhood) Simone’s cry of ‘all is true!’ and Sonia Saviange’s appearance, desperate and screaming with drunkenness, love and madness on the Rue de la Gaîté. The film draws from Vecchiali’s work its trust in actors, with the stubborn and deadpan Ingrid Bourgoin, who plays Simone with her quintessentially Parisian loquacity. As with Guiguet and Emmanuel Lemoine, Treilhou had met her at one of her places of work, a porn cinema in Montparnasse which would become the first of the three huis clos the heroine passes through over the course of the night (the second is a lesbian club, the third a car that takes her from the Grands Boulevards back to her home on the Ourcq canal). I love how, in this film — like in Femmes femmes — we quickly grasp the topography of each of these enclosed spaces. In the lobby of the porn cinema, of which we see nothing else, Simone and Martine (Martine Simonet) chat with the customers, rebuff them or joke with them, enter and exit the screens in a game of Fort-Da that lets slip out the off-screen moans of these invisible films that draw the men in. Simone Barbès is a chamber film, like Le Théâtre and Les Belles Manières, a kammerspiel that reconstructs material life while isolating it in a muted interior that nevertheless remains a ‘public’ space, open to encounters. I’ve mentioned the power of bodies in these films, but I’m equally fascinated by their unique locations and the way they are approached, the hospitality they possess, which seems to repeat en abyme that of the Diagonale house itself, founded on Vecchiali’s intuitive openness. [8]

Corps à cœur (Paul Vecchiali, 1979)

What stands out about the spaces inhabited in these films is their intimacy, the way they directly embrace the relationships between the characters in an interior mode. In the spaces of these films, people can always talk, go up to each other or at least simply observe one another. We are not, as with Rivette (always a little panicked when it comes to touch or faces) amid the purely exterior wanderings of Le Pont du Nord, with its characters that are ‘points on a map’, in a film that is essential for understanding the politico-urban shift that took place at the end of the seventies. Nevertheless, at this time Rivette’s concerns and those of Biette, Guiguet and Treilhou are not so distant: how do you occupy your time, especially when you don’t belong to the social criteria of the new society of the eighties that is taking shape, which will no longer be popular in any sense. When she won the advance on receipts for Simone Barbès, Treilhou suddenly felt her ‘change in social status’, [9] her ‘entry into the system’: ‘It tormented me for a long time, and it took me a long time to accept it emotionally.’ I also recognize in these films a diffuse consciousness of marginality: the kind where, quietly, ‘the goddess Homosexuality’ (as Barthes put it) watches over. I know how much the visual flirting on the Saint-Martin canal in Le Théâtre echoes the art of careful decipherment for which the film itself calls; I feel the distress of Hélène’s son for Camille in Les Belles Manières, and I feel that this distress is not one-sided, that it is echoed in the ambiguous rape that takes place in the prison; I recognize this site of exchanges, glances and downward spirals that is the nocturnal space of the lesbian nightclub in Simone Barbès, and the acuity it takes to sit there on the sidelines like the heroine. This attention for discreet signs, sidelong glances, clothes, hiding places, for the whole hieroglyphic and secret economy of cruising, for different bodies — I know that this also comes from that place. I also know that AIDS, shifting morals and finally technology would make this language almost illegible, planing down different lives and giving them access to a double-edged visibility: empowerment [10] and normalization.

After studying the Diagonale films, I ended up finding another common thread, albeit an ostensibly trivial one: there are photos on the walls. Perhaps this comes from Godard, but in any case it passes through Vecchiali [11] and takes on its full meaning in Femmes femmes, with those photos of bygone stars that line the apartment of Sonia and Hélène. The images appear in the montage through sudden inserts — they seem to judge the characters, and even seem, at the end of the film, to cruelly hound the poor, dying Sonia. Similar images are plastered on the walls of Dorothée and Hermann’s apartments in Le Théâtre, in the son’s room in Belles Manières, and in his mother’s bourgeois apartment (which he has fled), decorated with antique tapestries that are so many bigger than life [12] representations. Ezra Pound wrote: ‘You test a picture by its powers of endurance. If you can have it on your wall for six months without being bored, it is presumably as good a picture as you, personally, are capable of enjoying.’ [13] I see in these images a kind of theater of memory opening windows in the walls of these dark rooms, revealing the reference collection, the inheritance that watches the present action from the walls, just as the spectator does. The viewer comes ‘from the future’, while the images are the gaze of the past. Between the two lies what the Diagonale filmmakers attempted to ‘save’ from a society entering a new phase (what we did not yet call late capitalism): bodies, ways of speaking and moving, human relationships and the brouhaha they loved, but also works of art, so that we might watch and hear them again in a different light. If the films of Biette, Treilhou, Guiguet and Vecchiali are so important to me, and if they are indeed great films, it’s because they are made by spectators. Pasolini wrote that ‘for the author, the spectator is merely another author’. [14] We could invert his formula and say: ‘for the spectator, the author is merely another spectator’, without betraying the rest of his argument: ‘The spectator is not the one who does not understand, who is scandalized, who hates, who laughs; the spectator is the one who understands, who sympathizes, who loves.’ Vecchiali allowed his loving spectators to become authors, just as in Femmes femmes he offered this status to two out-of-work actresses. Biette, Guiguet and Treilhou became authors, but as cinéastes (according to the Biettean terminology [15] ), those who, as good sorts [bonne pâte], ‘serve themselves up to us [s’offrent à nous en pâture]’ — for to love means to relinquish. In so doing, they resemble what Biette so admired in Ernest Bour, who gave himself to the orchestra ‘so exclusively that uninformed listeners, or rather those accustomed to being taken in hand by the conductor, felt abandoned, alone, alone with the music’. Biette, Guiguet and Treilhou, without ceasing to be spectators themselves, taught me how to become one, and how to acquire, deep in the Diagonale abode, that special intimacy, that solitude of idle attention that is the only quality of one who goes to the cinema.

Originally published in Trafic, 120, Winter 2021.

Notes

After the death of the producer Jacques Le Glou, these films remained prey to those who had bought them from catalogues and hoped (in vain) to get a higher return than their potential audiences. Biette’s film has been available online since summer 2020 on the Cinémathèque française’s Henri platform https://www.cinematheque.fr/henri/film/46812-le-theatre-des-matieres-jean-claude-biette-1977, while those of Guiguet, Frot-Coutaz and Treilhou have been beautifully restored by La Traverse and, in the case of the latter two, released on DVD.

From Walter Benjamin’s journal, entry of 12 July 1934, quoted in Erdmut Wizisla, Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht – The Story of a Friendship, trans. by Christine Shuttleworth (Yale University Press, 2009), p. 59. The German original can be found in Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, seven vols and three supplementary vols, ed. by Theodor W. Adorno, Gershom Scholem, Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser (Surhkamp Verlag, 1972–1999), vi (1985), p. 526.

Interview with Serge Daney and Serge Toubiana on the occasion of the release of Les Belles Manières, Cahiers du cinéma, 298, March 1979.

Interview with Tifenn Jamin and Raphaël Lefèvre, Répliques, 7, 2016.

Interview with Jean Narboni and Serge Toubiana, Poétique des auteurs (Cahiers du cinéma, 1988).

According to Pierre Léon, who mentions this film, which is equally dear to him, in Jean-Claude Biette, Le sens du paradoxe (Capricci, 2013).

Translator’s note: l’espèce de chose mélancolie, a reference to Jean-Louis Schefer’s book of that title.

Marie-Claude Treilhou: ‘Vecchiali, as he often says, took people for who they were, not because they had filmmaking talent or had studied. He took you in if he liked you, if he sensed something in you. That’s how he accepted the script for Simone Barbès ou la vertu.’ Répliques, 7, 2016.

Ibid.

Translator’s note: in English in the original.

See in particular his Lettre d’un cinéaste (1983), which recounts his working day and ends with the photos that cover the walls of his bedroom-office.

Translator’s note: in English in the original.

Ezra Pound, ‘Paris Letter’, The Dial, 74:3 (March 1923), 273–280 (p. 273).

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism, ed. by Louise K. Barnett, trans. by Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett (Indiana University Press, 1988), p. 269.

‘Qu’est-ce qu’un cinéaste ?’, Trafic, 18, Spring 1996, later published by P.O.L. in 2001 in the collection of the same name.