We have no happiness. There’s no such thing. It’s only something we long for. [1]

—Anton Chekhov, Three Sisters

Serge Daney says that some films watch us grow up. He was speaking specifically about Rio Bravo.

It’s true of Gérard Frot-Coutaz’s Beau temps mais orageux en fin de journée, in my case.

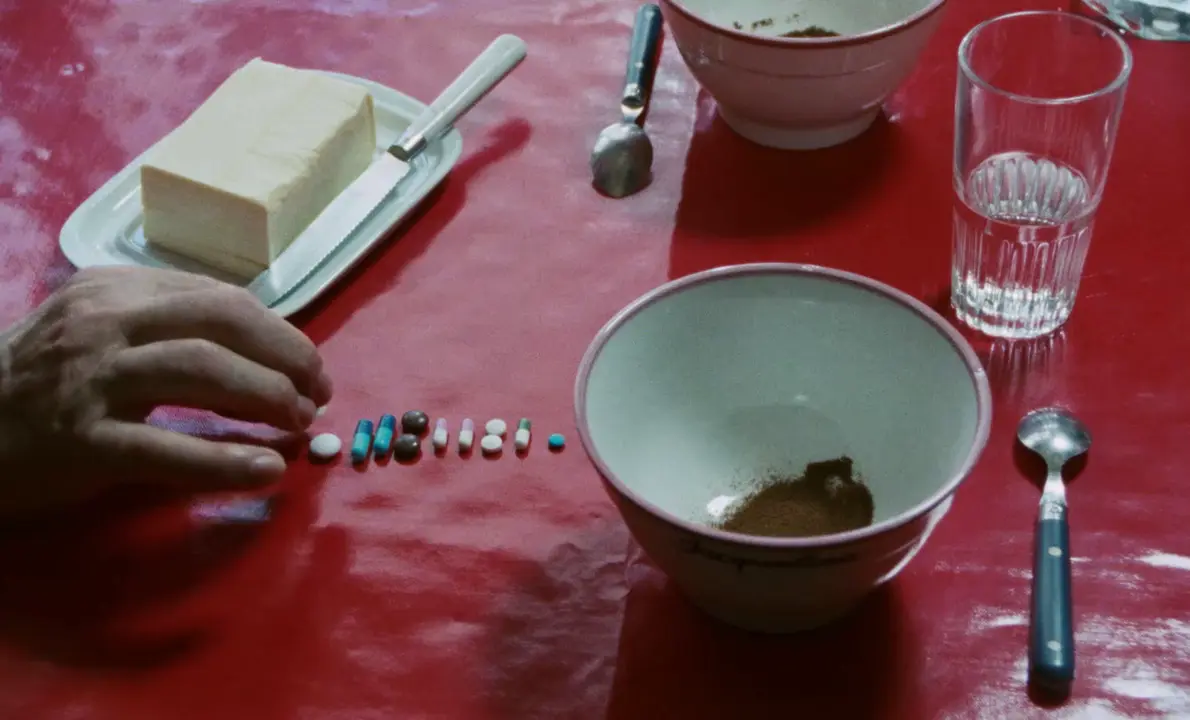

I discovered the film when it was released, and my joy came from the fact that it was the most perfect portrait of my grandparents that I had seen; it taught me things about them, of course, essential things: I finally knew what was going on between them when I wasn’t with them. Cinema had the power to make me invisible at will, to turn me into that famous ‘little mouse’ who could watch without being seen and thus not interfere in their attitudes, reservations, storms, feelings… And as I discovered all of that, I recognised them: my grandmother’s coquetry and her panics over nothing, my grandfather’s tempered outbursts and his inner turmoil, and their pills, a mathematical and colorful morning ritual that had always fascinated me and which became a fictional rhythm, a metronome for the brilliant acting of Micheline Presle and Claude Piéplu.

Beau temps mais orageux en fin de journée (Gérard Frot-Coutaz, 1986)

The film then lurked in the shadows of my memory until I watched it again two decades later — a rewatch prompted by the desire to show it to my partner, which is obviously not an incidental detail — and I realized how mistaken I had been: what was shown here was not my grandparents, but rather my parents, their unbearable quirks, their domestic squabbles that would have been funny if they weren’t so banally repetitive, the slightly overbearing and clumsy attention they paid to my love life and money matters… And despite this, there was still a joy there, but now different, no doubt more cruel, tinged with a melancholy that I hadn’t noticed as a teenager.

Finally, I watched the film again some years after that, as I was restoring it. And it was then that I was seized by terror: this was no longer a film about my parents, and even less about my grandparents, it was gradually becoming a film about me — I was catching up with this film, which had once been so many years ahead of me. I now had my own box of pills and irritable breakfasts, ‘she’ annoyed me constantly with her irrational fears, and when ‘she’ didn’t annoy me, I annoyed myself, and our children had become the object of all of our frustrations. Having started out as a humorous fictional depiction of my grandparents, the film now documented what I was, to the core and to the point of absurdity. How I had first grown up, then grown old.

In carefully carrying out the restoration work, on the one hand I was touching — finally — the very body of the film, its skin, its flesh, its arteries, and, of course, its eyes, which for thirty-five years had been watching me (first growing up, then growing old), and in that I was face to face with something of the hide and seek essence of cinema, a duel of gazes in which one does not exactly know who is in the shadow and who is in the light; on the other hand, I inevitably had the feeling that I was ‘restoring’ my grandparents a little, my parents a little, and maybe even myself a little. ‘Death at work’, as Cocteau defined it, was being perverted in the time it took to grade and mix, in reversing course, turning back time, giving life back to a film, and through it, to a lineage, to a personal history, to a jumble of stories… And the knowledge that at that moment the film was also watching me — watching me tinker with it, watching me believe that my ancestors were reappearing, even if only as ghosts, etc. — evoked in me a Pirandellian tumult… jubilant and melancholic.

One last confession: I believe in this film so much that I no longer dare to buy a roast chicken that would mark the hour of my death… even though I know that my partner’s gaze in the setting sun on a hill near Belleville would also be just as much jubilatory as melancholic, imbued with all the feelings accumulated through a life of companionship under the gaze of a great film.

P.S. A film that watches you is an anti-portrait of Dorian Gray; it ages less quickly than you do… A different essence of cinema, in which our projected portraits preserve the youth that flees from us.

Notes

Anton Chekhov, Three Sisters, in Five Plays, trans. by Richard Hingley (Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 200.