Cinephilia looks awfully pathetic in Luc Moullet’s Les Sièges de l’Alcazar (1989), but that’s part of the joke. Very few cinephiles have come to this film without already knowing something about the history of Cahiers du Cinéma: the medium-shaking directors it produced, their auteurist preoccupations, how they exploded around the world, and Moullet’s own history with both criticism and filmmaking. While every member of the French New Wave was a firebrand with an affection for disreputable American movies, Moullet’s status as one of the youngest Cahiers critics and a sort of kid brother to Jean-Luc Godard may have particularly inclined him to double down on the disreputable. Alcazar’s protagonist Guy is a barely-concealed stand-in for the young Moullet: he’s a precocious Cahiers critic with a fondness for the seemingly anonymous and trashy movies of Vittorio Cottafavi, armed with the trademark Cahiers willingness to sling mud in his writing. This film may have done more to raise Cottafavi’s critical reputation than any piece of writing could have done; whether that was a conscious goal of Moullet’s is left as an unanswered question. He enjoys sitting in the cheap front row seats intended for children at his local theater, the titular Alcazar, and hangs out with a group of fellow critics who might be even more off-putting and show-offy than he is (one of them claims to be a Sam Newfield auteurist). It’s not much of a life to some, but for those who track this film down, it might be the only one imaginable, and that winsome pitifulness is part of the fun.

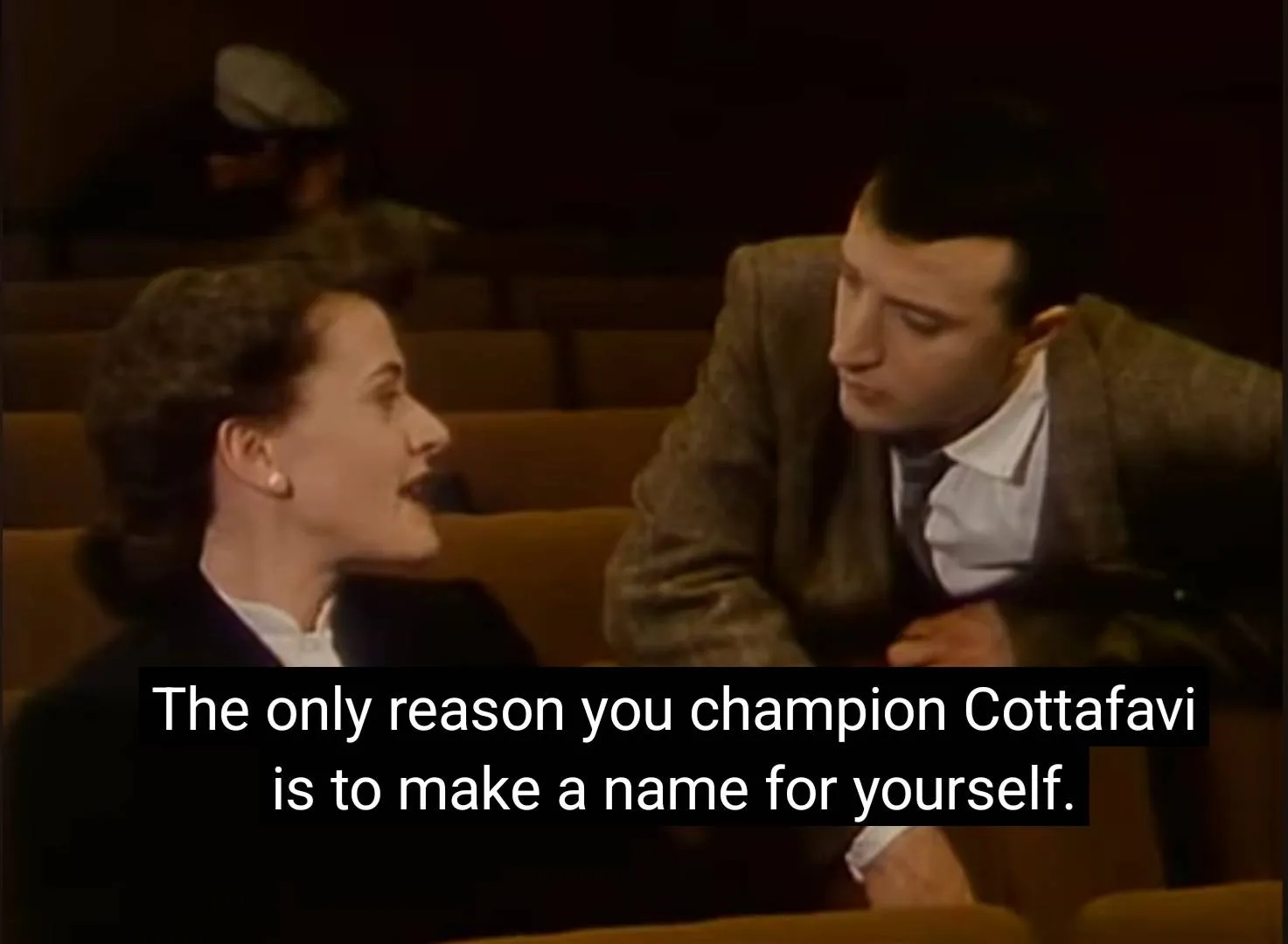

One lesser-known detail in Cahiers’ history, at least among those who see it mainly as a launching pad for the five most famous directors it produced, involves their (mostly) friendly rivalry with the critics of Positif. Positif was and is a left-leaning publication that wasn’t inclined towards praising the likes of Cottafavi back in the 60s, and viewed the political orientations of the Cahiers group with suspicion. Moullet’s father, incidentally, was a Hitler supporter who nearly got sentenced to death for it, and Moullet himself would go on to claim that ‘on fascism, only the point of view of someone who has been tempted is of any interest.’ Positif is represented in Alcazar by Jeanne, played by Elizabeth Moreau with a single eyebrow perpetually raised. She’s based on the actual Positif critic Michèle Firk, who may have been the only film critic to back up their political leanings outside of print by joining a revolutionary group, assassinating the U.S. ambassador to Guatemala, and committing suicide to avoid arrest. Jeanne is beautiful, intelligent, and, as an Antonioni enthusiast, has no affection for Cottafavi. Meanwhile, Guy is so self-absorbed that he initially thinks she’s trying to poach his interest for her own criticism. Jeanne finds Guy an intriguing window into the reactionary side of cinephilia, but mocks his bad breath in voiceover and ridicules Guy’s rube-ish pronunciation of his beloved auteur’s name to his face. Only in the movies would anyone think the two have a snowball’s chance in hell of making for a good couple, and those sentimental expectations are what keeps the film funny.

Despite their abundance of awful qualities, Guy and his friends are hardly the only rotten apples in the world of cinema. The people running the Alcazar might have a point about Guy’s snottiness, as he steals seats from children who can’t afford anything else, but they’re also penny pinchers who push chocolate ices to boost their profits and don’t really care about how the films themselves are treated. They will happily snip out a reel to extract more showings, indifferent to unwitting audiences; unwitting, that is, except for Guy. And after all, who could blame him for enjoying a private screening as his reward for noticing the proprietors’ skullduggery?

Money matters are generally beneath contempt in Moullet’s world. He never really found commercial success as a filmmaker, nor was he particularly preoccupied with it. His belief in anarchism and B movies frequently carried over to his running times. Alcazar is an unconventional 54 minutes, from a director unusually committed to making narrative short films. This habit was born out of a combination of necessity and an aspiration to become a new kind of Samuel Fuller or Edgar Ulmer. Alcazar was the concluding work of his 1980s run, perhaps the decade where he made his most beloved films. Among his shorter works, the great Barres (1984) tackles fare evasion in ways both funny and formalist à la Tati and Keaton, while Essai d’ouverture (1988) turns a Coke bottle’s packaging into a playground of capitalist frustrations. Brevity being the soul of wit, plenty of Moullet’s jokes probably couldn’t sustain a longer running time, and Alcazar was (as per usual) clearly shot on the cheap: only a few locations are used, and the film primarily consists of people sitting in chairs. It finds interesting common ground with Éric Rohmer’s better-known talking cinema, particularly notable given the polarity of Rohmer’s monarchism and Moullet’s anarchism. Moullet’s own writing on Rohmer is a little reminiscent of Jeanne’s skepticism about Cottafavi, and Nick Pinkerton has noted how Alcazar’s boys and their territorial connoisseurship aren’t too far from the similarly chauvinistic pissing-match values that feature in Rohmer’s La Collectionneuse. [1] Les Sièges de l’Alcazar is perhaps the closest thing to a stately Moullet film, given that he frequently made adjective-anarchic works that bounce like superballs, but the homemade B movie quality that he treasured so much in his criticism would always remain.

Notes

Nick Pinkerton, ‘Collect ‘em All!’, Employee Picks, 1 March 2021. Available at https://nickpinkerton.substack.com/p/collect-em-all.