I like to make things very simple. I am a great admirer of Mizoguchi's way of making films, which is the shortest way -- as opposed to John Ford's way. He's stronger than John Ford. It's interesting to find exactly the shortest way to present an idea or a landscape. [1]

In his essay on A Corner In Wheat (D.W. Griffith, 1909) Moullet praises Griffith’s simultaneous brevity and totality in portraying the capitalist mode of production and its instability — a brevity he claims is only possible in the fabulist presentation of the silent film. [2] In his signature conversational mode, Moullet claims that since A Corner in Wheat cinema has never reached an ‘an equal level of such concentrated density’. He praises Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902) for a similar reason, the density of presentation of its ideas within a short format. ‘[He] neither had sound, nor color, nor 3-D, but he has never been outdone.’ [3] Moullet has followed in Méliès' and Griffith’s footsteps by flattening his subjects so as to stretch them as thinly as possible in the shortest amount of time; though Luc takes it a step further and pokes holes in the maps he unfolds.

Because he knows he can’t recreate the fables of silent cinema — ‘The talkies brought too much realism’ [4] — Moullet’s short films intentionally appear slight in their content. Barres (1984) and Essai d’ouverture (1988), rather than depicting an entire economy, hone in on Parisian working class nuisances, the Paris Metro fare or the ultimate object of the West’s globalized consumerism: Coca-Cola. Moullet’s concern is to create the most dense film from variations on a singular physical action. Cutting corners comes naturally to Moullet, but it is his understanding of why, how, and where these corners exist that form the ethos of his oeuvre.

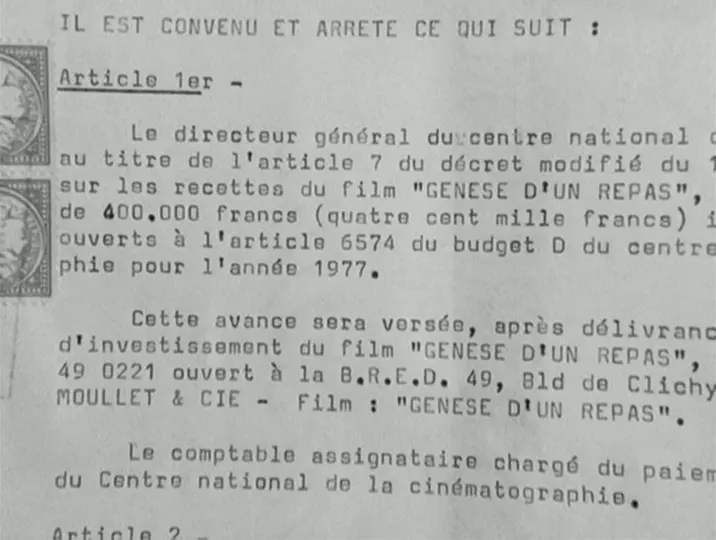

A Corner in Wheat fits the thematic content of an epic into its fourteen-minute runtime. Moullet, unable (and unwilling) to do so in the realm of sound cinema, makes a film eight times that length: Genèse d’un repas (1979) is Moullet’s longest film. As is typical of Moullet, we begin from a concentrated action and branch out. Moullet and his partner Antonietta Pizzorno are at the dinner table: bananas, omelettes, and a can of tuna sit in front of the couple. In a voiceover, he frames the motive for making Genèse through his personal curiosity: ‘You recognize these things, but you don’t know what they are. [...] I don’t know either. To find out, I asked for 40 million centimes from a public body, Le Centre du Cinéma. They gave it to me.’ Moullet’s comedic transparency is taken further when he follows the scene at the dinner table with a shot of the contract from the Centre; for Moullet the question is how his film might represent the entire economic genealogy of his subjects in the shortest amount of time possible — again, eight times as long as Griffith took. Here the subject is his film and how better to show its economy than by filming the contract?

Genèse d’un repas (Luc Moullet, 1979)

The film mostly cuts between interviews with workers and businessmen at varying stages of the production line (‘With my tight budget, I paid 50 francs for interviews in the Third World, 120 francs in France’), shots of labor, and the products themselves — usually back on Moullet’s dinner table. Here the film harkens back to A Corner in Wheat: class antagonisms collide in the edit, though Genèse has none of Griffith’s Victorian sentiment or the simplicity that renders that film a moral fable. Griffith stripped of his sentiment is pure analysis; Moullet doesn’t provide solutions but rather presents a stream of material realities: ‘It's difficult to make a film about economics that wouldn't be Marxist. But the film will not, at least at the beginning, be linked to some theoretical point of view.’ [5] The film is characterized by bluntness; structurally, Genèse d’un repas is made up of an accumulating list of statistics.

More contradictions are exposed. The Frenchman in charge of the shipping of bananas from Ecuador claims the unions are in favor of mechanization, while in the next shot the union workers speak of the threat mechanization poses to employment. Wages differ not only in quantity but in how pay is calculated — dock workers in France must get a fixed hourly wage, while the Ecuadorian workers get paid by the crate; the Ecuadorian dockers average about a third of the French wages, though they must work harder and in worse conditions to make a living. And the presence of French expat workers dispels any illusion of wages being proportional to economies, since the fishermen from France get paid the wages of five or six Senegalese fishermen. The conditions of workers in France are contrasted to those of the tuna canners in Dakar. The workers in France are not allowed the privilege of sitting, nor talking to their fellow workers, and even a smile brings reprimand. The interviews in Genèse d’un repas are not merely the talking heads of the common documentary detritus, but bodies in disharmony among the global reach of these industries.

The most ridiculous Moullet-ism in the film brings his investigation back home once again, in a scene in which Pizzorno takes off every piece of clothing she has until she is nude, reading off the labels where each article was produced. The source of Moullet’s dental implants and the mint currency from his wallet are specified, before the economy of the gelatin used to produce the celluloid that we are seeing images from becomes the final note of the film. In a survey of the West’s colonial power, Moullet does not have to create any absurd scenarios: the contradictions of capital present themselves as farce enough.

Notes

Luc Moullet, ‘Interview with Luc Moullet by John Hughes and Bill Krohn’, Kino Slang, 2014. Available at https://kinoslang.blogspot.com/2014/03/interview-with-luc-moullet-by-john.html.

Luc Moullet, ‘Ah Yes! Griffith was a Marxist!’, trans. by Ted Fendt in LOLA, 1, 2010. Originally published in Bref, 79, November 2007 Available at http://lolajournal.com/1/griffith.html.

Chef d’œuvre? (Luc Moullet, 2010).

Moullet, ‘Ah Yes!’.

Moullet, ‘Interview’.